24 November 2017

In recent decades, globalization and the development of high-speed transport have given rise to a new type of travel: short-term business travel. Goods trade, knowledge and know-how often function at the international scale, and many people are now obliged to make long-distance work-related trips. The reasons for these trips vary, but their duration is usually short, ranging from a day to a week. Some jobs require frequent business travel, from one to several times a month. We call the individuals concerned "highly mobile" or "hypermobile.”

Master thesis title: L’influence des déplacements professionnels sur le rapport à l’espace. Le cas des grands mobiles

Country : France

University: Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne (Paris)

Year : 2015

Research supervisor : Renaud Le Goix

In recent decades, globalization and the development of high-speed transport have given rise to a new type of travel: short-term business travel. Goods trade, knowledge and know-how often function at the international scale, and many people are now obliged to make long-distance work-related trips. The reasons for these trips vary, but their duration is usually short, ranging from a day to a week. Some jobs require frequent business travel, from one to several times a month. We call the individuals concerned "highly mobile" or "hypermobile.”

The emergence and development of these mobility situations are at the origin of spatial changes. However, despite the amplification of this phenomenon, few works focus on their geographical and urban impact.

Thus far, high professional mobility has, in general, been approached from a sociological standpoint, especially for its role as a social marker (Depeau and Ramadier, 2011; Gherardi and Pierre, 2010) and for its effects on family relations (Legrand and Ortar, 2011; Ravalet et al., 2014). Geographically-oriented works have focused on its effects on individuals’ geographical mooring (Gustafson, 2009; Dubucs et al., 2011). In addition, works focusing on high professional mobility generally include all types of the latter, including long-distance and weekly commuting or multilocational living arrangement, which are essentially regular forms and require travel limited number of places in the long term, unlike short business trips. In my thesis, "highly mobile" refers to any person who travels:

The rare studies that consider business travel as defined above, as their sole purpose of study, only analyze executive business trips (Gherardi 2008; Beaverstock et al., 2009). However, are far from being the only ones concerned. My thesis therefore proposes enriching our understanding of high mobility and professional travel by developing the following points:

This work highlights the fact that highly-mobile people adopt spatial strategies designed to minimize travel time (time away from home and from their usual place of work). This results in more intensive use of airport and industrial zones located on the outskirts of cities, as professional meeting places are often located in such areas for several reasons:

1/ Offices near production areas (factories, etc.) or storage facilities often serve as meeting places, especially for on-site team visits. Now, these sites are often located in outlying areas, close to major roads and air transport routes.

2 / When a choice of venues is available, highly mobile people prefer accessible places near major transport routes. This criterion impacts all scales: cities are often chosen for this reason and must therefore be well connected to the rest of the territory (regional, national, European or international, depending on the scope of the event). It is also a criterion in the choice of the location, as it must be easily accessible to all participants.

Julien, an executive in an oil company, often meets with project partners on “neutral” premises that belong neither to his company nor to that of the partner, so as to not to favor either:

« The criteria is a big city not too far from where they are, because we know it's easy for us, that we'll be able to maximize the time, that there will be a good transportation network and good hotels, that's it. We already have to fly to a city. We don’t want to arrive and then have a 4-hour taxi trip or 4-hour drive to get to another city on top of that. »

The choice of cities mainly depends on accessibility from the countries of both partners and the quality of the internal transportation network. When meeting with a partner located in Saudi Arabia, for instance, the city chosen was Dubai. Similarly, Pierre, a self-employed technical adviser to national doctors’ unions, which provides training in many French cities, prefers conference rooms located on the outskirts of major cities, to facilitate access for participants. For training in the Paris region, he usually chooses a conference room near Orly airport.

Consequently, travelers also tend to choose hotels located on the outskirts, close to their meeting places, to minimize travel time on site. This is also true to a lesser extent for dining and recreational activities.

The high professional mobility thus gives rise to new uses of the peripheral spaces of cities, reinforcing the importance of major transport routes for territorial organization.

However, contrary to popular belief, highly mobile people do not systematically favor large, global chains. Although these spaces are appreciated for their familiarity and ease of use, many highly mobile people choose, when they can, places they can feel attachment to, and that can serve as landmarks and friendly harbors in unfamiliar cities (e.g. family-run hotels with good comfort and services, local cafes and restaurants, etc.).

When made on a frequent basis, these trips alter people’s personal use of space, in regard to tourism and leisure. The places discovered during business trips strengthens people’s desire to travel and guides their choices in terms of tourist destinations. Business trips are often a source of frustration for highly-mobile people, who must travel to faraway and unfamiliar places, but do not have a chance (due to a lack of time) or the desire (due to solitude) to visit these cities. Traveling during their free time (weekends or holidays) is a way of alleviating the frustration of not having enjoyed a place. Hence, it is not uncommon for certain highly-mobile people to return to cities they visited for professional reasons in a personal capacity, in order to (re)discover the city from another angle. This desire to travel, however, also contradicts the fatigue to which business travel gives rise. The latter, conversely, incites them to visit familiar places during their travels, as a source of spatial and emotional attachment. Caroline, a researcher, describes this ambiguity between the desire to travel and the need for rest.

« I think you're less inclined to travel when you've got holidays. It's a little contradictory, meaning when you travel, you say to yourself, "Oh, I really want to travel for my own enjoyment," and when you come back and you're done and you think, “No way, I’ll just have a quiet holiday in the country.” You see, this summer, I’ve decided to go to the Alps. »

To the extent that they affect people’s personal and tourist mobility, business trips can affect areas not directly concerned by this type of travel.

This research is based on quantitative and qualitative analyses. Quantitative surveys using data from the 2008 National Transport and Travel Survey 1 aim to clarify the definition of high mobility and to characterize highly mobile individuals socially. The quantitative definition explored in this thesis is based on two variables: the number of work-related trips (excluding home-work commutes) of more than 100 km made in the month preceding the survey and the number of kilometers traveled during these trips. However, neither is entirely satisfactory, as the frequency of travel is rarely fixed, and rather can change depending on needs and the period. The size of the observation window described in the survey could therefore be extended, as only surveying the trips a month prior to the survey seems too restrictive for trips that are not necessarily regular. These quantitative analyses are also designed to characterize highly-mobile people socially, notably by questioning the veracity of the stereotypical figure of the highly-mobile person: a 35-45 year-old male business executive with a comfortable salary and who lives in a big city 2. It is also unfortunate that the survey could not provide more details regarding the reasons for professional trips, and that the internal travel within each trip is not described for trips of less than 100 km. On the contrary, it could be interesting to learn more about people’s mobility practices of individuals once on site.

To overcome the limitations of these quantitative operations, I also used qualitative analytical methods, wherein I conducted 12 semi-structured interviews with individuals who travel for professional reasons a minimum of once a month. I contacted individuals who were mutual acquaintances and then used the so-called "snowball" method 3. The objective of the interviews was to understand individuals’ spatial practices and habits during business trips, to understand the reasoning that underlies these practices organization, and to measure their effects on their personal mobility (including tourists). The interviewees were asked to describe their business trips in general (motives, frequency, duration, etc.), and to describe their last two business trips in greater detail. They were also asked about their feelings with regard to these trips in order to get them to reflect on their practices. Finally, we asked them to describe their personal mobility to measure business travel’s potential impact on it.

This master thesis makes three main contributions to the political and theoretical debates relating to the mobility of people.

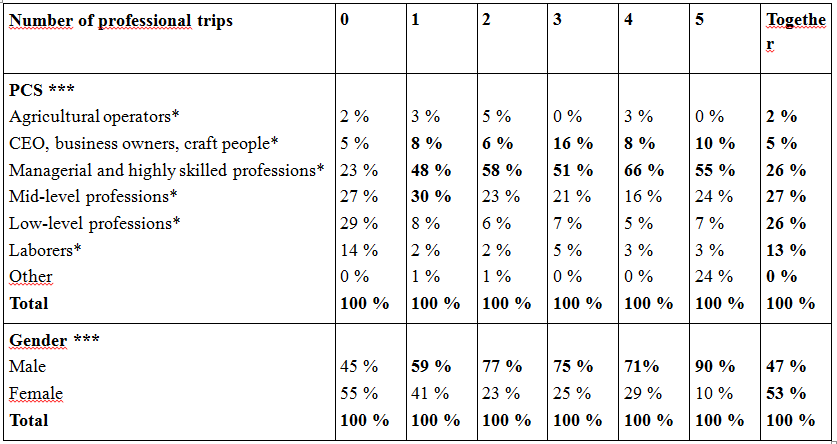

First, this work helps deconstruct the myth that highly-mobile individuals are only businessmen, in line with the work of Emmanuel Ravalet, Stéphanie Vincent-Geslin and Vincent Kaufmann (2014). Admittedly, men are more likely to travel for work than women (and with greater frequency), and managers are largely overrepresented among professionally mobile individuals. However, artisans, shopekeepers and entrepreneurs are overrepresented as well. Intermediate occupations are also very much present (though under-represented against the general population), as shown in the cross-tabulation presented below.

Interpretation: Senior executives and superior intellectual occupations accounted for 58% of people who had made two business trips in the month preceding the survey, whereas they represent only 26% of all individuals surveyed. Similarly, men account for 59% of the individuals who had made a business trip in the month preceding the survey, whereas they represented 47% of all individuals surveyed.

*(Table - Link between the number of business trips made in the month and individuals’ gender/socio-professional category.

Note: The three stars beside the PCS and Gender variables indicate that the p-value obtained for the χ2 test is less than 0.01.

Source: 2008 National Transport and Travel Survey, INSEE. Author’s calculations

Field: All of France, working person not including long-distance travelers not including daily commuters.

The interviews confirm that there is effectively wide variety of highly mobile people that included all age categories - from 24 to 62 – and a wide range of areas of residence. Additionally, several individuals had jobs that are rarely associate with "highly mobiles" in the collective imagination. For example, Claude, a podiatrist, frequently travels to follow athletes during intensive training sessions and competitions, thus dispelling the myth that they all hold executive positions.

Secondly, this work challenges the idea that the hyper-mobile individuals’ mobility is "reversible" 4 (Vincent-Geslin and Ortar, 2012). While individual trips do not destabilize individuals socially, as a whole they bring about changes in practices and spatial representations.

Thirdly, this work adds fuel to the debate on what high-speed transportation development policies to follow, notably the “all-TGV” policy. By making a larger area accessible in less time, these policies favor short-term business travel, whose territorial needs and impacts must be anticipated. High mobility situations are still marginal and thus have a relatively weak concrete impact on territorial planning (beyond industrial and airport zones). However, were they to become more widespread, their effects could become consequent. Contrary to current policies, many highly-mobile people expressed their desire not to have Wi-Fi available on transportation modes, which are among the few spaces left where they can still rest or work without interruption.

My thesis calls for further research on situations of frequent, work-related high mobility by differentiating them from multi-locational high mobility or long-distance commuting.

The effect of such high mobility on tourist and leisure mobility suggests more general effects on individuals’ personal spatial practices. As such, these results point to the need to further research on highly-mobile people’s daily use of space, focusing in particular on their relationship to their residential areas, in line with the work of researchers from the MEREV research program on people circulating between European metropolises (Dubucs et al., 2011). Does the high-mobility associated with frequent business trips strengthen people’s attachment to their city or residential area, or serve to uproot them?

As this master thesis has demonstrated, given the growing attendance level of airport and industrial zones as a result of business trips, it might also be interesting to analyze the effects of the latter on the territory through an approach based on the place rather than the individual. It is therefore a matter of identifying the possible impacts of this rise in business trips on the organization of these spaces, like, for instance, relocating service companies close to high-speed transport routes, or providing meeting rooms in such areas.

Beaverstock, J. V., Derudder, B., Faulconbridge, J. R. et Witlox, F. (2009). « International business travel : some explorations ». Geografiska Annaler : Serie B, Human Geography, 91(3):193–202.

Depeau, S. et Ramadier, T. (2011). « Introduction ». In Se déplacer pour se situer : places en jeu, enjeux de classes , pages 9–24. Presses Universitaires de Rennes, Rennes.

Dubucs, H., Dureau, F., Giroud, M., Imbert, C., André-Poyaud, I. et Bahoken, F. (2011). « Les circulants entre métropoles européennes à l’épreuve de leurs mobilités. Une lecture temporelle, spatiale et sociale de la pénibilité. » Articulo - Journal of Urban Research [en ligne], 7. Consulté

en ligne le 24/02/2017 : http ://articulo.revues.org/1810.

Gherardi, L. (2008). La mobilité ambiguë. Pour une sociologie des classes sociales supérieures dans la société contemporaine . Thèse de doctorat, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales et Université Catholique de Milan.

Gherardi, L. et Pierre, P. (2010). « Mobilités géographiques et écarts de pouvoir au sein de trois entreprises mondialisées. Mobiles, immobiles et ubiquistes. » Reveue européenne des migrations internationales, 26(1):161–185.

Gustafson, P. (2009). « More cosmopolitan, no less local ». European Societies, 11(1):25–47.

Legrand, C. et Ortar, N. (2011). « L’hypermobilité est-elle à l’origine de nouveaux modes d’habiter ? » In Depeau, S. et Ramadier, T., éditeurs : Se déplacer pour se situer : places en jeu, enjeux de classes, pages 57–72. Presses Universitaires de Rennes, Rennes.

Ravalet, E., Vincent-Geslin, S. et Kaufmann, V. (2014). Tranches de vie mobile. Enquête sociologique et manifeste sur la grande mobilité liée au travail , éditions Loco /Forum Vies Mobiles, Paris.

Vincent-Geslin, S. et Ortar, N. (2012). « Aller et retour : une utilisation réversible de l’espace. » In Vincent-Geslin, S. et Kaufmann, V., éditeurs : Mobilité sans racines. Plus loin, plus vite ... plus mobiles ?, pages 35–49. Descartes & cie, Paris.

1 This survey, conducted by INSEE on a ten-year basis, aims to describe the mobility practices of French people during both work and leisure periods. For the 2008 version, the data collection was spread over a year (from April 2007 to 2008), to take into account the seasonality of the mobility. A total of 18,632 people responded to the survey. Among other things, they were asked to describe all of their trips over 100 km in the four weeks preceding the survey. It should be noted that the professional trips for people whose jobs were inherently mobile (airline pilots, stewards, lorrydrivers, etc.) are not described in these databases. More information on the methodology of the survey is available on the Ministry of Transport’s website: http://www.statistiques.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/sources-methodes/enquete-nomenclature/1543/139/ inquiry-national-transport-displacements-ENTD-2008.html.

2 To this end, several regression models explaining the number of business trips made in the month are presented. The most successful model, the Zero-inflated Negative Binomial, is a two-part model: a first set of variables was used to estimate the probability of an individual being professionally mobile (number of business trips during the month prior to the survey not equal to 0) and; a second set of variables was then used to estimate the number of business trips made by mobile individuals.

3 Though this method may involve biases, as it uses a personal network, it nonetheless seems the most suited for overcoming the difficulties companies can pose for such research, namely, as L. Gherardi and P. Pierre note, mistrust of the social sciences, difficulty identifying interviewees and their limited availability (2010).

4 According to S. Vincent-Geslin and N. Ortar, all mobility involving travelling great distances via rapid transportation modes and in the short term are reversible because they do not demand any real change or represent a potential imbalance for the traveller. (Vincent-Geslin and Ortar, 2012, p.41).

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xTo cite this publication :

Magali de Raphélis (24 November 2017), « The influence of work-related travel on highly-mobile peoples practices and representations of space », Préparer la transition mobilitaire. Consulté le 09 May 2025, URL: https://forumviesmobiles.org/en/new-voices/12258/influence-work-related-travel-highly-mobile-peoples-practices-and-representations-space