In 2015, a vast project of pedestrianization of Brussels’ main central avenues was launched, radically changing the face of a city-center that had been designed for cars. The study assessed the impact of this pedestrianization on people’s lifestyles. It focuses both on how activities, seen as signs of different lifestyles, are carried out in the built and social environment of the pedestrian area, and how these activities fit into each individual’s life. The purpose of this study was to understand what lessons we can draw from a project of drastic car reduction in the heart of a major city, and to assess the extent to which such a project can help the transition towards more desired and sustainable lifestyles.

Illustration by Tom Itterbeek

Urban policies from the 1950s to the 1980s embodied a vision of Brussels as both a consumption hub and an administrative capital, designing it to become a “convergence point of the national motorway network.” 1 Public space was then planned for cars, with central four-lane avenues, relegating pedestrians to crowded sidewalks and underground tramways. In the 1970s, social movements challenged this concept of a speed-prioritizing city and called for a rethinking of its organization that rehabilitates the idea of slowness. Besides claims pertaining to sustainability and citizen participation, other arguments focused more on the need to increase the attractiveness of Brussels’ city center and draw middle classes back inside the city. Indeed, Brussels had experienced a strong phenomenon of periurbanization, with well-off households settling in the mid or outer suburbs, leaving the city center largely to the working classes. At the same time, because of its high multifunctionality (in housing, businesses, administrations, tourism and leisure), the city center attracted people on a supra-local scale, leading to accessibility and mobility issues.

In this context, a project to extend Brussels’ pedestrian area to the central boulevards was launched in 2015 (called “le Piétionnier” in French), but it was poorly thought through. Indeed, the political decision to pedestrianize was rushed and aimed first and foremost to make Anspach Boulevard a car-free avenue, without any in-depth thought about how this space could be reinvested and reclaimed. This decision came as a response to a citizens’ initiative called PicNic The Streets: in 2012, a philosopher wrote an article in a daily newspaper calling on people to invade Anspach Boulevard for an open picnic. The article was massively shared on social media and over two thousand people showed up. It was a case of pedestrians reclaiming a space that was then dedicated to cars.

Public authorities thereby faced the challenge of reconciling the public’s aspirations to free up Brussels’ public space, as expressed through the PicNic The Streets event, with the interests of motorists, in a city that was still widely thought of as being an “auto-city.” They were therefore reluctant to make any profound reconsiderations as to the place of cars throughout the city and as a result, pedestrianization projects always implied the reorganization of car traffic onto adjacent streets in order to avoid penalizing motorists. From the very beginning, the project was therefore caught in a paradox, both trying to remove cars from the city center all the while ensuring that cars could still have access to it.

Subsequently, the project’s implementation was hesitant. It relied on three plans: one for mobility, one for reorganizing the public spaces and one for commercial development. The first was implemented almost two years before the second. Works on the reorganization of public spaces began in September 2017 on several sections of the boulevard. At the beginning of the study, the pedestrian area then included zones at different stages of developmentt: some were already properly developed while others nearby were still untouched or under construction.

The heterogeneity of the whole area was made worse by the diverse types of mobilities that use it. While the area was initially intended for pedestrians, other active modes (bicycles, scooters...) are permitted throughout, while in some places buses are allowed and even some vehicles under certain conditions: residents, deliveries and even taxis. A single lane of motorized traffic was also reopened in some parts of the pedestrian area, following legal claims against the town planning permits and police decisions.

The pedestrian area’s extension project caused much controversy, especially because of the lack of public consultation and the unpreparedness with which it was decided. It is in this context that the Brussels Center Observatory was created within the Brussels Studies Institute 2 to objectively debate the new pedestrian area and assess its impact on the city’s functioning. To monitor the current project on how pedestrianization affects lifestyles, a research team was established within this Observatory involving experts in sociology, anthropology, archaeology and geography. Working alongside them, a team of experts from the TOR Research Group at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) – leaders in the field of Time Use Surveys for several years – implemented a device for keeping spatial activity diaries.

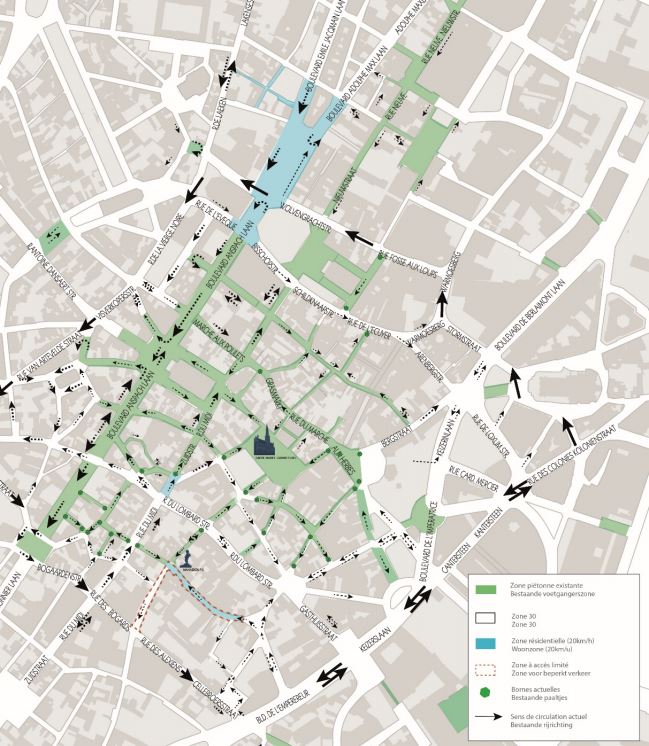

Map of the pedestrian area (source: City of Brussels, March 2019 ; reviewed by the authors)

The research aimed to understand how the organization of the pedestrian area impacted the lifestyles of those who frequent it, as well as those who used to frequent it and those who live in the area without necessarily frequenting it. Indeed, many different kinds of people may have been impacted by the extension of the pedestrian area: inhabitants of the pedestrian area, people who work in the area, occasional or regular users, inhabitants of the city of Brussels, former users of the city-center, etc. The researchers therefore hypothesized that the project had an impact not only on the regular users of the city center, those who are visible in the public space, but also on those who aren’t regularly seen there, whose entire range of activities, from shopping habits to leisure, mobility and social connections may also have been reconfigured. The project may have also influenced their representations of the area, of their living environment, of Brussels or even their opinion on the pedestrianization of city centers.

The researchers also postulated that it is possible to observe, in the public space of the new pedestrian area, traces of the lifestyles of those who now use it. The diverse populations and uses that inhabit this space, coupled with the heterogeneity of the redevelopment which is still in different stages of advancement, makes this whole pedestrian area a true laboratory for studying the social interactions, mobilities and behaviors of those who use it. Three sub-hypotheses were thus proposed:

To investigate these questions, researchers relied on a double methodology, consisting of two research modules conducted simultaneously.

The researchers first emphasize how the project’s lack of focus, from its conception to its implementation, impacted how people perceived and appropriated the new Piétonnier pedestrian area. This lack of focus refers to the unclear nature of the new pedestrian area’s status and vagueness in defining its identity; for example, interviews conducted show that respondents find it difficult to imagine what the area might look like once completed and how it might work.

First of all, political officials were very unclear in communicating their ambitions for the city center with regards to the pedestrianization project. Indeed, it involved different actors (cabinets, administrations, parapublic bodies) and different levels of power (communal, regional, federal) that don’t necessarily share a common vision and sometimes disseminate conflicting messages about the project and the city center. This unclear communication wasn’t helped by differing positions expressed by the media, associations, businesses, citizen platforms, etc.

As a result, this lack of clarity generated apprehension, misunderstanding and rejection from a majority of respondents (residents, traders, local employees, public service workers, real estate developers, etc.). During the period between the closure of the area to cars and the beginning of works, the area was perceived as being abandoned for several months. This sense of abandonment was reinforced by the lack of information about the duration of the work or its different phases, which was particularly stressful for local business owners for whom the project represented significant losses.

One of the reasons for of this lack of focus surrounding the project is that its status has changed several times, with vehicles sometimes being allowed to pass through, and other times not. For instance, before March 2019, one of the sections was defined as a meeting area where cars were allowed to circulate. In March 2019, the section was pedestrianized again and was then later reopened to traffic for several weeks in the summer of 2019, without clear communication. These hesitations led to misunderstandings, with motorists unsure of which lanes they were allowed to use, and pedestrians sometimes surprised to see cars in a zone that they thought was pedestrianized. Consequently, incidents often occurred - such as pedestrians crossing in front of cars - as well as a general sense of insecurity reported by the interviewees. The researchers further found that city services took a while to properly grasp the legal status of the area, in particular the police, leading to problems between users and police officers. For example, the owner of a delivery company reported that on several occasions, his drivers were fined for driving within the perimeter despite being there during authorized delivery times.

At the same time, this period at the beginning of the project’s implementation also allowed for cases of spontaneous appropriation of the space, thanks in particular to temporary facilities along the boulevard such as ping-pong tables.

Being 925 meters long and 26 meters wide, the new pedestrian area has a strong longitudinal profile, inherited from its former function as an urban boulevard. Three public squares interrupt the area’s linearity: Place Fontainas in the south, Place De Brouckère in the north and Place de la Bourse in the middle; this delineates six sections, each with its own identity and atmosphere. For those surveyed, the linearity of the new pedestrian area is what makes it specific; its “enormous” and “excessive” nature, according to the words of some respondents, contrasts with their perception of a public space. Because of its linearity, the pedestrian area is experienced more as a promenade or as a place for strolling than as a public square where people stay in place. And yet, the researches observed more varied behaviors.

The researchers saw how users invest this space differently depending on the hours of the day and days of the week. They show that despite the extended space dedicated to them, pedestrians mostly use the sidewalks to move around while people on bikes prefer the central strip. On weekday mornings, people seem to use the pedestrian area in a mostly functional way, not stopping, mainly transiting through the area; at noon, traffic increases, with pedestrians overflowing onto the central strip, some wandering while others pass through, and the public space is generally occupied more statically. In the late afternoon, researchers again observed more functional trips with people returning home from work; when the weather is nice, families are also present (going home from school, children playing in the pedestrian area, etc.). Evenings vary according to the seasons; in winter, the pedestrian area is mainly deserted, while in the summer it is packed with users who settle there and occupy the whole space.

People’s use of the pedestrian area also differs according to the facilities that are available there. In particular, the researchers observed how the benches were designed and occupied by people, noting that they were part of what made the pedestrian area attractive as they enable multiple uses.The benches that were installed are large and wide with backrests that don’t run the entire length of the bench; as a result, they can be used as simple benches but also as picnic tables thanks to the central backrest.

The zone’s ground coating is another element that influences people’s uses. The choice to have unsmooth, irregular pavements makes it difficult for certain categories of users to get around, especially people in wheelchairs or with strollers.

Finally, the researchers also showed that the construction works themselves, present throughout the whole pedestrian area, also created their own uses. They arouse the curiosity of passers-by, who stop to look over the fences. While during the day the fences force users to bypass the construction sites, in the evenings when the work stops, people regularly ignore the restrictions: many open the fences to get across quicker, while others even settle inside the construction sites - this is the case for some homeless people who take shelter there at night or store their belongings there.

The interviews complement the observations carried out in the public space by providing insights into people’s experience of the pedestrian area. First, they revealed that the local inhabitants, especially those who often walk or use public transport, spend more time in the pedestrian area than they used to. Whereas before the pedestrianization, the strong presence of cars and associated nuisances (pollution, noise, trouble crossing roads) led many respondents to avoid the boulevard, they now use it more often thanks to how is easy it is to navigate. They see it as a connecting element in Brussels’ city center. However, from another point of view, pedestrianization is sometimes experienced as having created a strong disruption in east-west connections within the city center, especially by motorists who can no longer drive through it and have to take other routes that they aren’t necessarily familiar with, leading some to cancel their trips or not use their car.

However, while the lack of cars is appreciated by pedestrians, the fact that the space is now shared by different and new modes of transport creates its own sources of insecurity. For example, the presence of bicycles or scooters during rush hour gives pedestrians a sense of insecurity, as well as the presence - legal or not - of motor vehicles in the pedestrian area or at intersections with non-pedestrian lanes. This insecurity particularly affects parents with young children or the elderly.

Another form of insecurity, linked to crime, is subject to debate among respondents. While some feel unsafe in the pedestrian area because they see it as a cut-throat street, others claim that the high number of visitors makes them feel safer. The researchers showed that some respondents associated various occupants of the pedestrian area with crime, complaining that pedestrianization has attracted pickpockets and drug dealers. Generally speaking, “marginal people” (homeless or vulnerable people who hang around the area during the day) who are numerous throughout the pedestrian area, are perceived as a source of insecurity - especially in relation to alcohol. The interviews also revealed that there is a gender-based sense of insecurity affecting some women. When observing the pedestrian area, the researchers witnessed some cases of men catcalling women. One respondent also pointed out that the place and position of the benches also contributes to women’s sense of insecurity, as men can just sit there and stare at them as they go by.

The researchers also point out the important issue of cleanliness in the pedestrian area, which many respondents mention. Indeed, many view the pedestrian area as dirty, partly due to poor waste management. In fact, during their observations, researchers often saw garbage bags left unsupervised and unorganized in the public space, often close to the many food establishments and cafes. This sense of uncleanliness further tarnishes the pedestrian area’s reputation.

Despite these problems that the researchers identified through their interviews and observations, the pedestrian area is also perceived as being a friendly area; the numerous café terraces liven up the boulevard, while the area hosts various events from protests to street shows.

The interviews were also an opportunity to explore how pedestrianization had changed people’s lifestyles and examine whether it had led them to reduce their use of cars. However, the research took place during a transitional phase where the development works were not completed; as a result, the researchers could only observe limited impacts of pedestrianization on people’s mobility practices.

Overall, they identified a difference between people living in the city center and those living in the outskirts. The inhabitants of the city center report walking a little more than before and using the pedestrian area more often as they can now cross it more easily. They also use their cars a little less than before the pedestrianization, although they didn’t use them much then. However, these inhabitants of the city center do report that pedestrianization has impacted their social life: some indicate that their relatives no longer want to come to visit them because of how difficult it is to drive into the city center, and so they are now the ones who more often than not travel to go and see their relatives.

For people living in the periphery, who often prefer to travel by car, pedestrianization has led them to avoid the city center, or to go there by other means than by car. Some, however, have not changed their mobility habits and continue to use their cars when they go to the center, as they know the area well enough to find alternatives.

Finally, the researchers show that beyond the observable behaviors and lifestyles that unfold there, the pedestrian area is an interesting subject of study because it constitutes a space that polarizes debates, an arena where several imaginaries collide. They use the image of a fight, showing a struggle between different imaginaries carried by various actors who weigh differently in the game: some have more ease and tools than others to support and materialize their visions for the city.

Two imaginaries are developed: on the one hand that of an appeased city for pedestrians in opposition to a city designed for cars; on the other, that of the future of the city center.

The new pedestrian area embodies the imaginary of a city made for pedestrians, in connection with the idea of a city that is less polluted and more environmentally friendly; it also defines itself in opposition to the automotive city. This imaginary is supported in particular by the Brussels-Capital Region through various mobility plans, such as the IRIS 2 Plan put in place in 2011, which aims to combat the omnipresence of cars and promote active modes and public transport. Subsequently, a new Regional Mobility Plan (Good Move) aims to make Brussels a walkable city where everyone can find basic services within walking distance of their home.

The pedestrian area thus symbolizes a shift in power, to the disadvantage of those who support cars. However, this shift is not fully championed at the level of the City of Brussels; for example, the mayor never uses the word “piétonnier” (the name of the new pedestrian area), instead speaking of the “central boulevards”; researchers point to electoral issues and note that the opposition between pedestrians and motorists is too sensitive a subject to be addressed head-on. Indeed, cars are still very present in the imaginary of Brussels and those who defend them have protested the pedestrianization project by deploying arguments that rely on the victimization of motorists, who find themselves “relegated to a fraction of the road” and “stigmatized” (Freesponsible association).

These opposing points of view are reflected in the interviews, especially between the respondents living in the city center and those living in the outskirts. While the former enjoy being able to cross the pedestrian area more easily, the latter generally view the project unfavorably. For some respondents, the noise, car horns and bustle are part of city life and what makes it lively, and that is more desirable than what they perceive as a large, empty, lifeless space. According to them, the city as a public space should be accessible to cars. Meanwhile, people living in the city center are generally in favor of pedestrianization.

As a result, public authorities are faced with these tensions between those who defend cars and those who support pedestrianization. In their analysis, the researchers therefore saw public policies as a compromise aimed at removing cars from the pedestrian area without penalizing motorists. Car parks were set up close to the pedestrian area so that the city center remains accessible to cars. As such, the pedestrianization project doesn’t fundamentally challenge the central place of cars, as they remain too closely connected to the economic life of the center. Located in the heart of a metropolitan city center, the new pedestrian area remains a destination in itself and must be both accessible and attractive: therefore, both imperatives – i.e. making cars invisible in a calmer city center all the while ensuring that cars can still access it by other main roads - pursue the same quest for attractiveness.

Within the city, two levels are potentially in conflict: the level of the whole city and the level of each neighborhood. In other words, the global and globalized dimension comes into conflict with the local, “inhabitant” dimension. In the case of the new pedestrian area and the controversies surrounding it, the researchers highlighted an opposition between these two dimensions, between visitors and inhabitants. They find that it is difficult to reconcile the goal of creating a pleasant city for inhabitants with that of revitalizing the center’s economic attractiveness by targeting visitors and tourists, especially considering that the pedestrian area is at the heart of a European capital that relies in part on its economic, tertiary and commercial activities. The pedestrian area thereby questions the scale on which we imagine the city of Brussels.

In fact, in the interviews, the respondents worry that the goal of increasing the center’s attractiveness will take precedence over the interests of local inhabitants and small business owners. They point in particular to the transformation of the pedestrian zone’s commercial landscape, with the arrival of large retailers taking over local stores, or shops tailored to an upper middle-class clientele, unsuited to the modest households that inhabit the area. Some respondents also fear what they call a “disneylandization” of the city center, through projects and facilities that favor tourists at the expense of local users. In particular, there has been a surge in available accommodation for tourists in and around the city center, such as many new listings on Airbnb, which could eventually drive out the more modest local inhabitants and encourage gentrification. Another striking example of how the pedestrian area has been transformed in pursuit of attractiveness is the “Belgian Beer Experience” project which is set to open up in the Stock Exchange building. To offset its cost and pay its employees, it would require no less than 400,000 visitors a year and is therefore considered a major tourist attraction.

The case of Brussels therefore reveals that while pedestrianization can locally reduce the negative impacts of cars (noise, pollution, spatial appropriation) and offer pedestrians the opportunity to reclaim public space, such a policy is not without its difficulties. This project seems in keeping with the analysis offered by Brenac et al. 3 of European city centers, where, according to them, the main motivation for pedestrianization is to raise attractiveness; such projects are likely to benefit the dominant economic actors and be detrimental to local inhabitants, business owners and users, and all without fundamentally challenging the place of cars on a metropolitan scale.

Download the synthesis (in French only)

Download the full report (in French only)

Download the appendices (in French only)

1 DE VISSCHER, J.-P., NEUWELS, J., VANDERSTAETEN, P. and CORIJN, E., 2016. Brève histoire critique des imaginaires à la base des aménagements successifs des boulevards, In : CORIJN, E., HUBERT, M., NEUWELS, J., VERMEULEN, S. and HARDY, M. (eds), Portfolio#1 : Cadrages - Kader, Ouvertures - Aanzet, Focus. Brussels : BSI-BCO, pp. 135-147, http://bco.bsi-brussels.be/portfolio-1/.

2 The Brussels Studies Institute (BSI) is a research platform bringing together 27 research centers and more than 250 researchers from 6 different universities specializing in various fields. It consists of a team of academic and nonacademic experts who support research projects and help disseminate the findings. BSI is currently pursuing 15 research projects involving teams that are multidisciplinary, multi-stakeholder, inter-university and cross-community, tailored to the subjects at hand. The Brussels Center Observatory (BSI - BCO) was formed within the Brussels Studies Institute (BSI) to deal with the controversies raised by the pedestrian area project and render the debates more objective. It studies the effects of pedestrianizing central avenues on the multi-scalar functioning of the city-metropolis. This Observatory now includes around 50 academics and researchers from various fields, affiliated with 15 research centers and linked to 5 different universities.

3 Thierry Brenac, Hélène Reigner, Frédérique Hernandez. Centres-villes aménagés pour les piétons : développement durable ou marketing urbain et tri social ?. Recherche Transports Sécurité, NecPlus, 2014, Piétons, 2013 (04), pp.267-278.

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xTo cite this publication :

Gabrielle Fenton et Jean-Louis Genard (17 January 2019), « City-centre, pedestrianization and lifestyles », Préparer la transition mobilitaire. Consulté le 20 May 2025, URL: https://forumviesmobiles.org/en/project/12832/city-centre-pedestrianization-and-lifestyles

Projects by Forum Vies Mobiles are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 France License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at contact.

Other publications