07 February 2019

This research offered a geographical provocation in studying the use of running as a form of transport. Although rarely thought about in such terms, running is a surprisingly common and important contemporary mode of transport globally !

Thesis title : Running as Transport: a geographical provocation

Country : United Kingdom

University : Royal Holloway, University of London

Year : 2014

Research supervisor : Professor Phillip Crang

This research offered a geographical provocation in studying the use of running as a form of transport. Although rarely thought about in such terms, running is a surprisingly common and important contemporary mode of transport globally. While in developing areas of the world, whole journeys may be made by running due to lack of choice, running’s prominence as a transport mode is increasing within developed areas of the world too, even where alternatives exist. Based upon research conducted within the UK, this project investigates two such occurrences of running as transport within developed countries. The first, emergency running, is an unaccounted, rarely recognised but commonplace form of transport, which people employ to ensure punctuality. The second form of running as transport, and one that warrants a little more context, is that of run-commuting. In this article I focus mainly on run-commuting.

Run-commuters need to find their space in the commuting landscape. ©IAMRUNBOX

Run-commuting is the practice of running to and/or from work. It is a practice that has gained prominence and visibility over recent years, both on the streets and in cultural discourse. While very little is known about the practice, there has been a growth of initiatives and discussions surrounding the practice across the world. From run2work in the UK, The Run Commuter in the USA, Corrida Amiga in Brazil, and Turnschuhpendler in Germany to the smaller communities in South Africa, Denmark and Australia, there has been a growth of organisations seeking to encourage run-commuting and share hints and tips for those partaking in it. This has coincided with various run-commuting initiatives taking place around the world and even the establishment of companies and products tailored specifically to run-commuting. This growing cultural significance of run-commuting mirrors an increased prominence on the streets too. While there are no definite figures as to this prominence, perhaps the best estimate comes from Strava, the activity tracking giant. Their latest report on 2018 indicates that globally, run-commutes logged on their platform increased 70% from 2017, which itself increased by 50% from 2016. They claim that a total of 21,781,323 separate run-commutes were logged in 2018. These averaged 6.6km in length and most commonly took place in the UK and Germany where run-commuters averaged 3.29 and 2.88 weekly trips respectively. Run-commuting is more common in larger urban areas, with London often being billed as the global capital of run-commuting.

Run-commuters are not homogenous however, there can be many differences within their practices. While most run the entirety of their commute, many combine running with another mode of transport (a train most commonly) to complete their journeys to/from work. While most carry a backpack to transport the ‘stuff’ they need at both home and work, others dislike running with a bag and drop the ‘stuff’ off when travelling by another mode of transport instead. While many can shower at work, others use nearby gyms to do so, while others only opt to run home to overcome this issue. Some run-commuters run the same route every commute, while others vary their routes to explore their city and take in the sights. This all demonstrates that while run-commuting can be logistically challenging to achieve, with enough planning and organisation, it is a flexible enough practice to meet these varied needs and desires.

The research seeking to understand these types of running as transport was undertaken as part of a MA in Cultural Geography. The thesis itself drew on work in the culturally-inspired field of mobility studies as well as research more commonly associated with transport studies. Both fields, which had explored a wide range of mobilities, had seemingly not attended with any great depth to one of the most ubiquitous forms of human movement – running. In applying mobilities research to running, this research also brought mobilities research into closer conversation with literature in sport studies. Running is more commonly conceptualised as a practice associated with sport, health and fitness, and reframing it as a transport-related practice represents a novel aspect of the research.

This thesis employed a diverse range of methods in order to understand the various practices of running as transport. In order to understand the brute facts of movement, meanings and embodied experiences relating to run-commuting, a survey of run-commuters in the UK was conducted. This elicited 235 responses, mostly from larger urban areas, such as London and Birmingham, or smaller cities with pre-existing cultures of active commuting, such as Cambridge. From these respondents, 10 participants were selected for interviews in order to explore their motivations and experiences of run-commuting. The selected interviewees were all living in Guildford, an affluent town about 30 miles south of London and the study sought to use a case study town in order to explore running-as-transport cultures. The selection of interviewees aimed at achieving as broad a sample as possible, exploring run-commuting practices within a range of ages, jobs, genders and commuting types. Half of the interviewees were female, half were male and all ranged from 27 to 60 in age. All interviewees had white collar jobs in business, research, education or government. A mix of ordinary interviews and go-along interviews were used, depending on the feasibility and desirability for the participant. In the go-along interviews, I joined the participant on their run-commutes in order to interrogate the experiences of run-commuting with as close a temporal and spatial proximity as possible. These run-commutes ranged from 3 to 8 miles; some ran the whole way to work, others ran to another mode of transport, most commonly a train. An ethnographic approach was adopted to understand emergency-running in a train station (Guildford), in which observations of people running were recorded across five consecutive week days for eight hours each day.

Simon Cook conducting a go-along interview

Theoretically, the first contribution of the project is to bring together different fields of study in understanding mobile practices. As noted earlier, mobilities research and transport studies had engaged little with sport studies. This project demonstrates the potential of engaging these fields in conversation, particularly around ideas of embodied practices, where sport sociology and physical cultural studies have much to offer. Connected to this, it challenges the classification of particular mobile practices as either sport or transport. In run-commuting especially, this project has explored a practice that blurs this boundary with interesting consequences. For example, it challenges the traditional space-time separation of commuting and sporting practices, asking them to co-exist within the space-times of rush-hour commuting corridors (i.e. walkers and runners moving at different speeds along the same streets). In turn, this is producing new interactions and encounters during the commute. For example, do runners belong more in a cycle lane (because of their speed) or in pedestrian space (because of their technology)? Is it acceptable to board a bus sweaty, in order to complete multi-modal journeys? Are runners permitted to run in a railway station to make their departing train? These questions surrounding how run-commuters manage to fit into commuting landscapes and what rights to space they have, are still being played out daily in streets all over the world. This blurring also poses a question of which organisations should be responsible for run-commuting, if any. Would the responsibility for encouraging and provisioning run-commuting lie with transport planning organisations or with running/sport organisations?

This work also added to arguments about reimagining the commute and the value of travel time. In particular, it invites us to think more widely about how commuting can be ‘productive’. The understanding of there being inherent value in travel time has often centred on the ways in which travelling can be seen as economically productive, rather than just a waste of time. This idea has generally focussed on the ability to both do work on the move, such as on a train, or on the opportunities to relax whilst travelling (reading, sleeping, window-gazing, catching up with friends/family), which in turn can make people more productive once at their destinations. However, run-commuting invites us to consider this productivity more widely to include physical activity and the productive jobs it performs - maintaining physical/mental health, completing ‘training’, and freeing up the time these activities would have occupied elsewhere in the day. In turn, run-commuting and its productivities also invite an adoption of a wider understanding of efficiency/convenience within transport mode selection. Run-commuting requires efficiency/convenience to be viewed on the scale of a whole day or even a week rather than just at the scale of the journey itself. Interviewees talked about run-commuting as a way of harmonising the competing demands of life, notably those which pertain to the realms of work, home, family and leisure, including obligations of work, childcare and running training programmes: “Allows me to fit training for races into my work/family life”, “Time effective way to get in training miles” and “It provides training time that I wouldn’t otherwise be able to justify”. Only by viewing run-commuting in these terms can we make sense of why run-commuters may select a slower, more physically demanding and logistically challenging mode of transport.

In regards to policy contributions, this project invites attention to be paid to active forms of transport beyond those of walking and cycling. Attention to practices such as run-commuting reveals creativity surrounding how daily life can be managed through mobility, how public health agendas may be implemented more widely through transport, and places much greater emphasis on the workplace in providing for such practices through a range of hard and soft measures. Hard measures relevant for run-commuting - those interventions which have a physical presence - could include the possibilities of running lanes in the streetscape, public water fountains, sweaty carriages on a train, workplace showers, storage options and changing facilities. In many ways, the ever-present nature of a backpack acts as a stop-gap for run-commuters when the hard measures do not yet meet their needs. Many endeavour to pack just the “bare bones really, just the stuff I need. I actually bought a set of smaller towels just so I don’t have to take a big towel with me because I need to get other things in there you know”. The aim to pack light is because of the embodied experiences of running with a backpack, which for many is unpleasant, enough even to act as a barrier to taking up the practice in the first place: “as a runner, while I have considered running to work I find it impractical ... I don’t like the idea of running with a backpack on my back”. Relevant soft measures, those which do not require anything to be built, could include initiatives such as flexible working hours and the promotion of active commuting.

Lastly, in focusing on the mundane ways in which people move, this project places a much greater emphasis on the importance of multi-modality and on adopting a door-to-door approach to transport and mobility planning/policy. Many commuters’ journeys involve the use of more than one method of transport; however, much transport planning and intervention focuses on the main mode of transport used for the commute only. This project’s investigation of running as transport demonstrates different ways in which people combine multiple modes of commuting. Many run-commuters run to a train and onwards again after alighting, combining running and rail voluntarily. However, running also plays an often involuntary role in rail mobilities, acting as an emergency mobility to ensure passengers make intended departure times. These forms of running as transport demonstrate the multiple yet often hidden ways in which running and train mobilities combine but equally, the difficulties commuters can have in combining these. Train stations are not designed for people to run in and often actively discourage it. Adopting a door-to-door approach to mobilities would attend to these intersections of different modalities much more centrally and work to increase the efficiency of these important spaces as sites of interchange.

This project suggests that the practice of run-commuting has emerged as a growing and rapidly changing practice occurring all across the world. This increase invites a much greater investigation of this practice, with particular attention needing to be paid to its geographies, the processes through which it has emerged and is changing, as well as the complex actualisation of run-commuting practices. In this way, run-commuting can act as an interesting case study into how active and sustainable transport modes can emerge, take root and be sustained, as well as the impacts that such changing practices can have on people, spaces, and wider society.

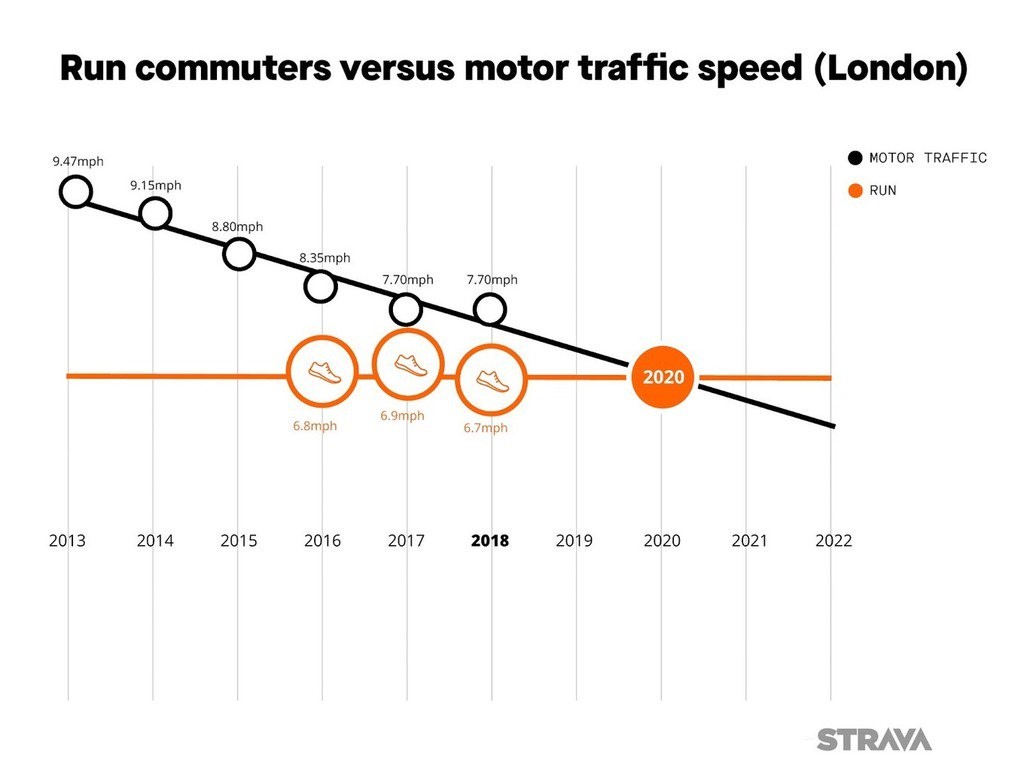

Trajectories of run-commuting and motor-traffic speeds in London. ©Strava

More broadly, this project into running as transport invites a greater exploration of how multi-modality actually happens and the ways in which bodies, design and materials engage to enable journeys from door-to-door. Both forms of running as transport investigated in this project reveal the significance, yet also difficulties, of combining multiple modes of mobility for commuting. A more detailed investigation of how this happens and how it could be improved, especially for more common multi-modality journeys (such as walking and bus/train), would be most welcome in helping to produce effective and efficient transport systems.

The project has also invited the broadening of understandings around travel time, productivity and efficiency/choice. Many of the logics of run-commuting stand in opposition to traditional transport rationales, and investigating further how productivity and travel time can be understood in different ways would be extremely helpful, particularly in understanding active travel beyond walking and cycling.

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xMovement is the crossing of space by people, objects, capital, ideas and other information. It is either oriented, and therefore occurs between an origin and one or more destinations, or it is more akin to the idea of simply wandering, with no real origin or destination.

En savoir plus xTo cite this publication :

Simon Cook (07 February 2019), « The Rise of run-commuting », Préparer la transition mobilitaire. Consulté le 29 April 2025, URL: https://forumviesmobiles.org/en/new-voices/12852/rise-run-commuting