21 February 2019

Although often studied as a homogenous phenomenon, migration practices are actually complex and multifaceted. Recognizing that migration takes many different forms was the underlying premise of this thesis. The purpose of this research was therefore to explore how structural changes have reshaped the organization of labor in India and how migratory practices adapt and readjust themselves to these new and evolving structures of the labor markets.

Thesis title : Modernization, labor markets and circulation in India. A mixed and multiscale approach to internal work migration.

Country : France

University : University of Bordeaux

Year : June 2016

Research supervisor : François Combarnous (Professor and Research Director, University of Bordeaux, GREThA) and Isabelle Guérin (Research Director at IRD, CESSMA)

Mobility is part of daily life for a large proportion of Indians living in villages, as they resort to different practices depending on the seasons, needs, constraints and opportunities. Whether it is to move to a nearby village following a marriage, to commute to the closest city, to return to the village for a religious ceremony, to relocate to one of the countries’ main cities or to perform a simple trip (a pilgrimage, tourism, etc.), the many movements of the Indian population are the result of how India’s society, economy and geography are structured. Yet, few studies have focused specifically on the relationship between the liberalization processes and labor-related migrations within India. Indeed, liberalization of India’s labor market and of the economy at large have produced significant social and economic changes that call for a new approach and new tools to better understand migratory behaviors, especially in rural areas which so far have been fairly ignored.

Despite India not having a strong rural exodus (according to the World Bank, in 2015 almost 70% of the Indian population still lived in rural areas), back-and-forth movements between rural areas and urban work areas have multiplied, in part thanks to the growth in demand in non-agricultural sectors and improving means of transportation and communication. Significant efforts in education (especially in the southern states) have also contributed significantly to breaking down the barriers between urban and rural areas. Once limited to agricultural work, rural populations - in particular the young and educated - now have access to non-agricultural jobs in the city, thus encouraging movement. However, while these patterns are becoming more widespread, not all villages are evolving at the same rate, meaning that migration habits are far from uniform.

Although often studied as a homogenous phenomenon, migration practices are actually complex and multifaceted. Recognizing that migration takes many different forms was the underlying premise of this thesis.

The purpose of this research was therefore to explore how structural changes have reshaped the organization of labor in India and how migratory practices adapt and readjust themselves to these new and evolving structures of the labor markets.

To achieve this, we first focused on studying how the evolution of India’s labor markets contributed to changing internal migration patterns. Then, in a second stage, we looked at the characteristics and specificities of these migratory practices. We identified a variety of migration styles that differ greatly and that are always determined by factors such as space and social groupings.

This thesis aimed to combine a study of labor migrations with an analysis of labor markets in the particular context of India. We therefore sought to analyze and understand, on one hand, if the economic, political and social structures, at a global level, had a significant impact on migratory movements and, on the other, if the socio-economic characteristics of migrant units (such as castes, gender, class, etc.), embedded in a particular local context, guided migratory choices and opportunities. To answer this, we followed a multiscale approach, combining both macro- and micro-level analyses.

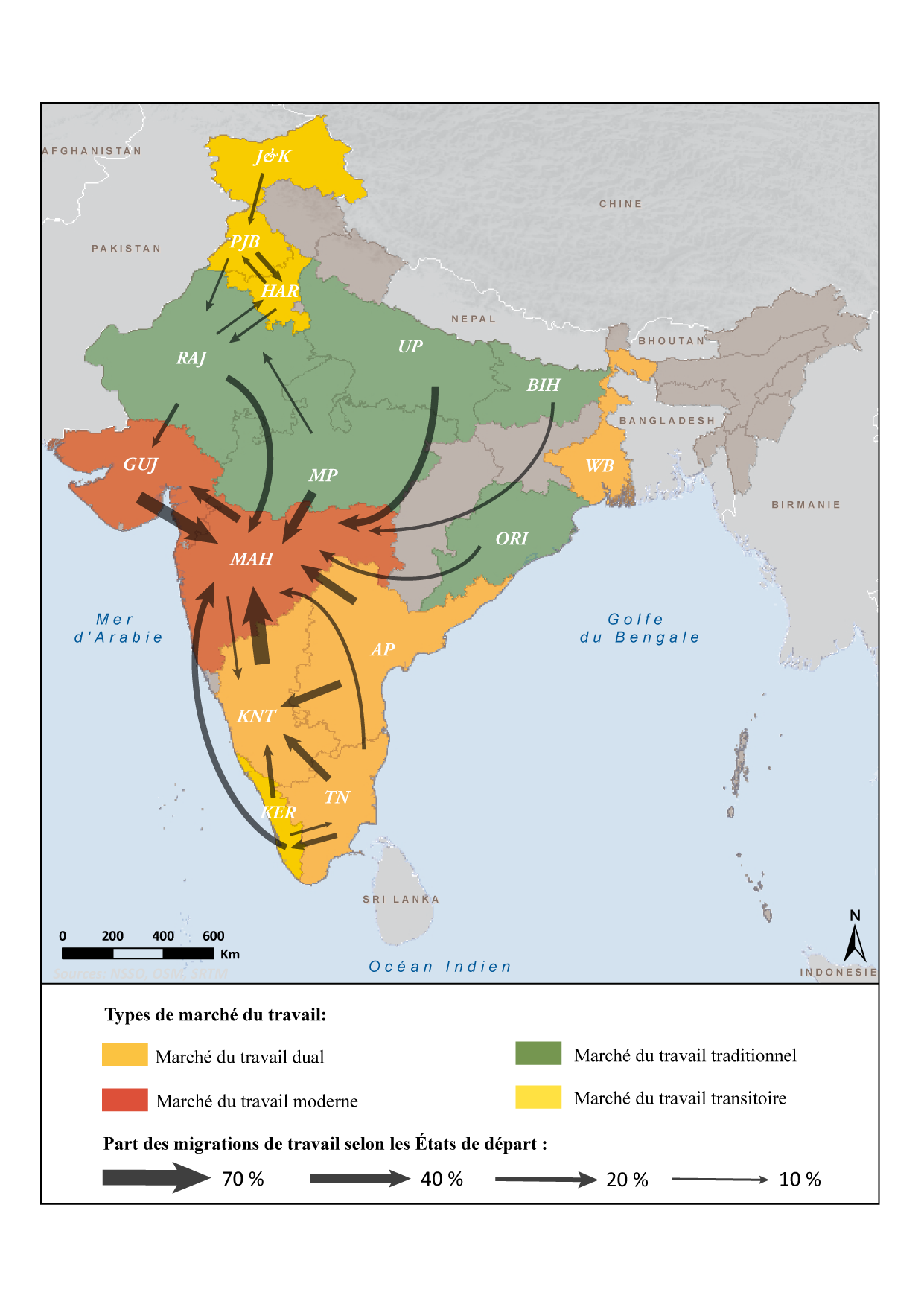

First of all, to identify the major trends at the national level, we built a typology of the labor markets in India based on the characteristics of the labor markets within each State in terms of the employment structure within different industries, informality of employment, job quality, etc. Thus, four types of labor markets were identified, highlighting regional spatial inequalities within the Indian subcontinent and differences in modernization 1 between these labor markets. We could then establish a gradation of these labor markets in terms of their modernization on a regional level, ranging from states that are still heavily reliant on a labour-intensive primary sector with low productivity, to states that feature secondary and tertiary sectors that are far more developed and productive. From this typology, we were able to study the labor-related migratory flows which we then spatialized in order to make them easier to read and to identify their patterns (see Figure 1). This spatialization reveals that the more “modern” states are also the most attractive. In contrast, the more “traditional” states saw increased departures of people towards more “modern” markets.

©Sébastien Michiels

Finally, by using a gravity model 2 we were able to identify with greater precision how labor markets, as structural elements, impact labor movements. A given labor market’s modernity is a factor that encourages immigration patterns simultaneously reducing emigration towards other forms of markets. In contrast, the traditional aspects of a labor market are unattractive and trigger labor-related migrations.

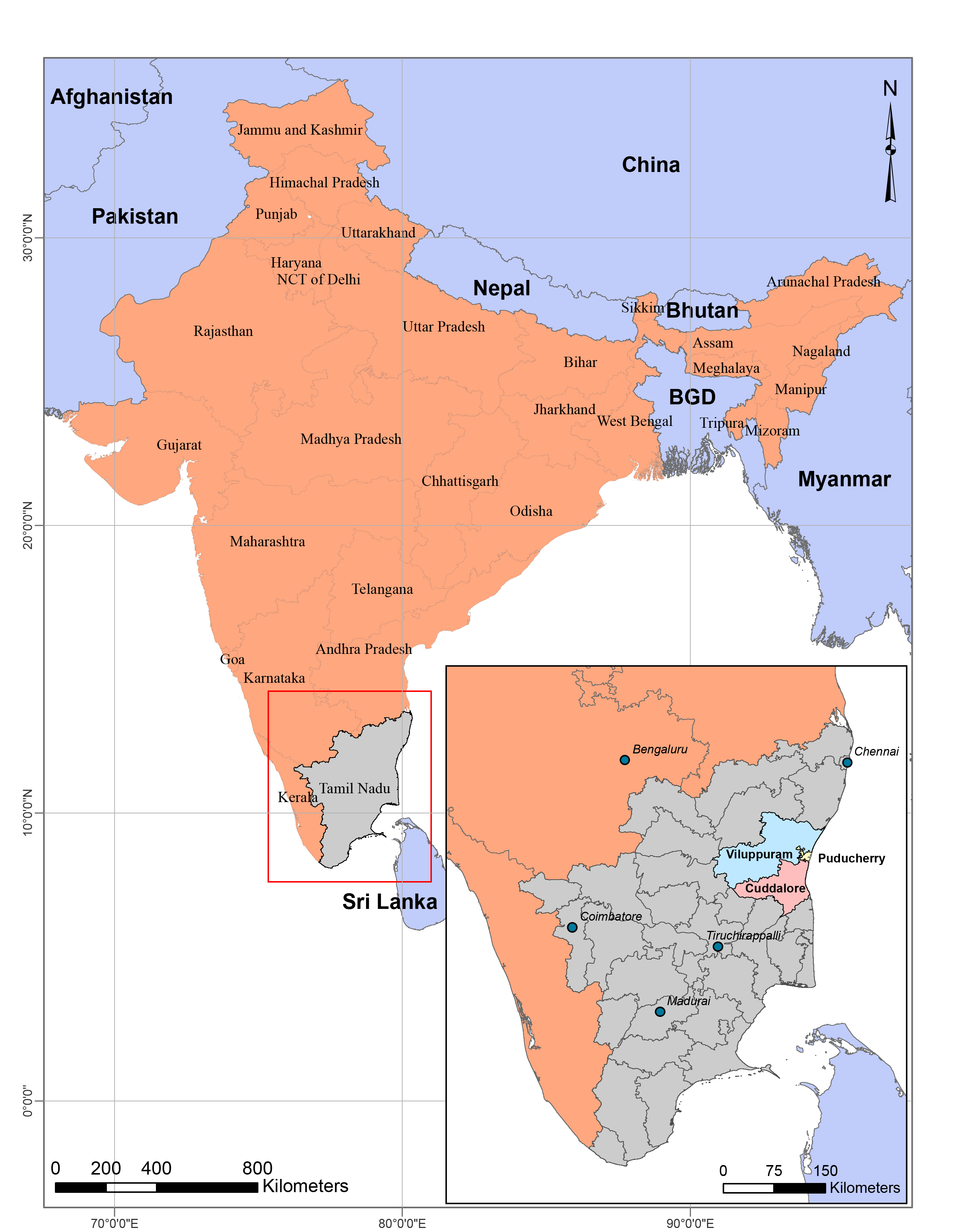

The second part, which focuses on an empirical study conducted in a rural area of Tamil Nadu (see Figure 1), allowed us to develop a more contextualized approach of migration practices in India. In the first stage, we used a socio-economic approach - considering that economic practices, whatever they may be, are embedded in social, cultural and political institutions - to represent the structural mutations facing Tamil rural areas. In the second stage, and based on these observations, we used a mixed approach combining qualitative (life histories, participant observation and focus groups) and quantitative (based on the RUral Microfinance and Employment survey carried out in 2010 with 405 rural households) methods.

We studied the regularity of migration patterns and the forms they can take. To do this we used exploratory multidimensional data analysis (a Multiple Correspondence Analysis, followed by a Hierarchical Cluster Analysis) which enabled us to identify on the one hand the diverse forms of migratory behaviors and on the other the different profiles of migrating households.

First of all, we identified five forms of mobility:

First of all, we identified five forms of mobility:

The difference between these various forms of mobility therefore hinges mainly on the type of migratory work (agricultural or not; qualified or not), its duration, its recruitment method (whether through an intermediary who organizes the migration or in a more individual fashion) and whether it constitutes a primary or supplemental activity.

From these quantitative analyses five distinct profiles of migrant households emerged:

Castes and classes (measured by levels of income, assets and savings) are of course major factors in establishing a typology of households, but the level of land ownership, the diversity of activity and the precariousness of living conditions are also important elements for distinguishing types of households.

This double typology has allowed us to identify a certain diversity in labor-related mobilities, characterized, among other things, by the persistence of certain kinds of labor (in particular relating to enslavement practices) and by the development of new forms of migration (especially in non-agricultural urban employment).

Finally, we resorted to qualitative interviews with migrants, whose narratives allowed us more specifically to study their chosen migration strategies and the constraints in organizing migration practices. This empirical study allowed us to deepen our understanding of the rural world in Tamil Nadu, in particular when meeting all the stakeholders involved in the migration channels, and improved the overall research by supplementing, illustrating and sometimes challenging the results of the quantitative approach.

Approximately 60 interviews were conducted between 2009 and 2015. Here is an example of an interview that highlights the diversity of migratory practices and their extremely segmented nature.

©Sébastien Michiels

With this second qualitative stage, we were able to analyze what meaning these individuals gave to their practices and to identify the main determinants of migration while taking into account the logics of segmentation that influence the labor market (including caste, class and gender). The range of profiles we established demonstrates the various migration strategies that can occur in the rural parts of Tamil Nadu. Whether these migration strategies are the result of necessity, as is the case for the vast majority of brickyard migrants, or of a pursuit of opportunities, they take place within an institutional web that intertwines factors such as local labor market structure, village remoteness, social networks and segmentation in land ownership. While caste and class continue to influence migration patterns, social categories evolve and the increasing development of interactions between villages and cities tends to encourage more diverse migration practices and strategies.

©Sébastien Michiels

First of all, contrary to many studies in which migration is seen as a homogenous phenomenon, we have demonstrated that such a vision is inappropriate in the case of the India. Indeed, we have identified many different forms of migration, each responding to its own dynamics and characteristics. These results appear all the more relevant as the migratory strategies adopted by individuals or households (strategies which should always be considered as part of a web of constraints) may be different even though their migratory behavior is the same. Therefore, we believe that labor migration as studied here in the case of India, far from being a homogenous phenomenon, requires a comprehensive and multidimensional analysis of its practices - practices which are themselves in a permanent dialectic between structural constraints and individual/family strategies.

Another key finding concerns inequality. It appears that migratory activity remains segmented according to caste and class (with some overlap), as well as in terms of gender. In this sense, we observed that migratory behavior tends to perpetuate the logics of social reproduction, especially in remote villages where “traditional” hierarchical structures still organize social relations and work. While we see a graduation in migration practices (see Figure 4), the strong correlation with class and caste shows how social reproduction operates:

We also observed the persistence of gender inequalities which, despite significant progress in terms of education, continue to limit mobility opportunities for female populations. Indeed, their confinement for reasons of social prestige and their lack of opportunities outside the village (even for young and educated women) are significant barriers to entry into the labor market for women.

Furthermore, the available infrastructure in their local village and more generally their living conditions play a non-negligible role in migration processes. The pressures that exist for much of the year on the labor supply in the local market, partly due to poor irrigation infrastructure and repeated droughts, have encouraged the development of migration patterns towards non-agricultural activities - especially in brickyards (see Figure 5) - that have become durable and institutionalized. Furthermore, circular migration, which is accentuated on the one hand by the development of small urban centers, transport and communication (i.e. improved roads and bus networks, Internet access even in remote areas, etc.) and non-agricultural work, and on the other by the persistence of seasonal migration, is destined to continue and become more complex. Indeed, the economic, geographic, political and social changes that are taking place in rural areas are expected to lead to the development of new variations in labor-related migration patterns and to increasingly complex migration strategies.

We therefore believe this study contributes to the literature on the circulation of labor in India, offering a comprehensive reading of migration practices.

Beyond having identified a variety of migration practices, this thesis has highlighted several points. On the one hand, it revealed the persistence of migration channels that perpetuate the enslavement of the most vulnerable populations. On the other, it showed the development of new and more positive forms of migration, although they are usually limited to the highest levels of Indian rural society. The spatialization of labor migrations allowed us first of all to see how India’s unequal development is caused by a political desire to energize the modern sectors of large cities while neglecting the countryside - despite the fact that two-thirds of India's population still live there. Furthermore, classifying the different types of migration also helped us identify these vulnerable populations and understand their components by recognizing that labor migrations contain heterogeneous situations. Finally, the qualitative interviews were very informative, allowing us to illustrate the diversity of migration practices in the evolving rural areas of Tamil Nadu. Indeed, we were able to see how there is a tension between people’s ties to the traditional lifestyle of their village and their more modern aspirations to be part of the attractive urban world. Additionally, we observed how patterns of enslavement and empowerment can appear or be reproduced.

Despite undoubtable theoretical and empirical contributions, however, this study lacked one fundamental dimension, a dynamic aspect that would have made it possible to study these migration practices over time. This limitation was partially overcome when a second survey (Networks, dEbt, Employment, Mobilities and Skills in India Survey) was conducted in 2016-2017 among the same households as the RUME survey referenced in the thesis. This new survey now enables a longitudinal analysis of migration practices, which is a fundamental dimension given how this is a field of study that is under constant and rapid change.

Ciculatory lives in Western India

1 Modernization is understood here as the transition from a “pre-modern” or “traditional” society to a so-called “modern” society, characterized by the expansion of processes of industrialization, tertiarization, urbanization and individuation.

2 Gravity models are used to determine the intensity of a relationship between spatial units, taking into account their potential (for example, demographic weight) and their distance.

3 The concept of a "dominant caste" was defined by Srinivas [1971: 10] as being numerically large and occupying a high place in the local caste hierarchy, and owning a substantial part of the local arable land.

4 The Dalits (previously known as Untouchables) are a group of individuals in India who are excluded from the caste system and traditionally relegated to demeaning tasks, for little or no pay, and often considered to be impure from a religious point of view: they are beggars, butchers, fishermen, hunters, cemetery caretakers, midwives, etc.

5 The Other Backward Class (or OBC) is an administrative category of the Indian population and consists mainly of lower-ranking castes (Shudras). They are most often farmers, breeders and craftsmen and represent slightly more than half of India's population.

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xMovement is the crossing of space by people, objects, capital, ideas and other information. It is either oriented, and therefore occurs between an origin and one or more destinations, or it is more akin to the idea of simply wandering, with no real origin or destination.

En savoir plus xA lifestyle is a composition of daily activities and experiences that give sense and meaning to the life of a person or a group in time and space.

En savoir plus xPolicies

Theories

To cite this publication :

Sébastien Michiels (21 February 2019), « Labor markets and circulation in India : new ways of life », Préparer la transition mobilitaire. Consulté le 09 May 2025, URL: https://forumviesmobiles.org/en/new-voices/12871/labor-markets-and-circulation-india-new-ways-life