For the 2020 Paris municipal elections, many proposals and claims were made on the future of the ring road, the 35 km ring road around Paris: removing it, redesigning it as a main road with traffic lights, creating green spaces, making several dedicated lanes to promote different modes of transport, etc. The Mobile Lives Forum wanted to explore the option of totally removing it. What consequences would this have on the Parisian, metropolitan and regional scale? Under what conditions could this removal be part of a transition towards more desired and sustainable lifestyles?

Illustration : Caroline Delmotte – Forum Vies Mobiles

There are many reasons for putting the removal of the ring road on the political agenda: environmental problems, noise, visual pollution; urban divide; questioning the legitimacy of such a big highway that symbolizes an all-car ideology that is now obsolete, etc. Yet, the Postcar study revealed how people in the Ile-de-France region are heavily dependent on cars, and unevenly so depending on whether they live in Paris, the suburbs, or periurban and rural areas. While we see an increasing dualization of public policies that strongly question the place of cars within Paris all the while neglecting the other areas of Ile-de-France, the Forum entrusted a group of students from the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne with a research project on the current uses of the ring road, the problems that would arise from its removal and the redistribution of its uses on the scale of the various affected territories (Paris, suburbs, metropolis, Ile-de-France) and the conditions under which its removal could be part of the transition to desired and sustainable lifestyles.

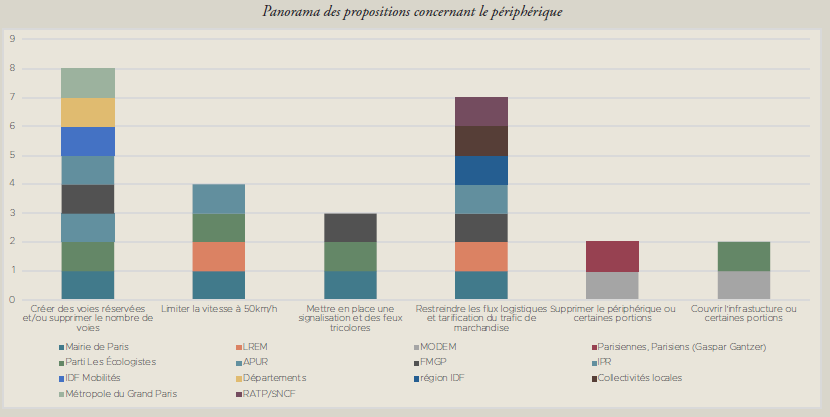

At first, the students established an overview of the different proposals for the ring road’s future; they questioned the representations underlying these proposals, in particular regarding the place of mobility in people’s lifestyles and of cars in their travel habits.

Then, the students examined the ring road and its uses using three methods: first, they analyzed data from the 2010 Global Transport Survey (EGT, Enquête Globale Transports), second they ran route simulations on Google Maps to identify alternatives to the ring road for various itineraries, and third they conducted interviews with users.

These interviews also allowed them to understand the relationship that users have to the ring road and identify six typical user profiles, based on their uses, social profile and place of residence: a senior executive living in the outer suburbs; a senior executive living in the inner suburbs; a worker/employee; and a student living near the ring road.

The students then conducted a forecasting workshop with about 20 participants who put themselves in the shoes of the different user-profiles identified, to think about scenarios in which the ring road’s removal could be part of the transition to desired and sustainable lifestyles. Two levers in particular were considered: modal shift and avoidance.

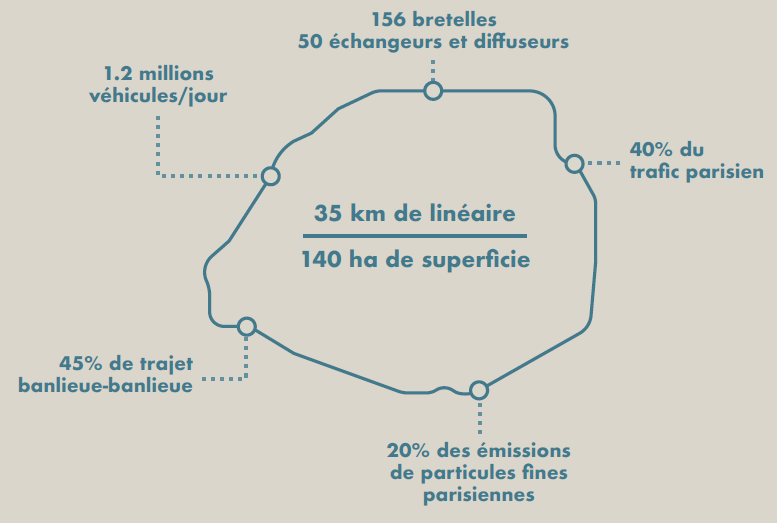

The ring road - the 35-kilometer-long ring road around Paris - is the busiest urban road in Europe, with 1.2 million vehicles per day, or 40% of Paris’ traffic.

Key features of the ring road

The ring road is a disruptive element between Paris and the neighboring cities. This disruption is more or less important depending on how the gates (called portes) are designed, especially whether they have multimodal transport options, easy access for pedestrians and bicycles and are coherent in terms of landscape, architecture and functionality.

For example, in the north of Paris, the ring road between Porte de la Chapelle and Porte de Clignancourt constitutes a strong division between Paris and the suburbs, which has seen a growth of informal settlements since the 2010s. Conversely, Porte Dorée, with the Bois de Vincennes forest, enjoys important continuity between the spaces located on either side of the ring road, thanks to the infrastructure being underground and a gradual transition from city to green spaces.

In recent years, several works have been published about the future of the ring road. In a 2016 report, the Paris Urbanism Workshop (APUR, Atelier Parisien d’Urbanisme) proposed measures to reduce the division caused by the ring road by building crossings and green spaces that would create some landscape continuity. In 2018, the Metropolitan Forum of Greater Paris (FMGP, Forum Métropolitain du Grand Paris) worked on the future of mobility in Ile-de-France and proposed that the ring road be transformed into an urban boulevard. The proposed measures aim to reduce car dependence and promote public transport and soft mobility, as part of a thought-process that isn’t limited to Paris but that instead includes the ring road in the wider metropolitan area. Finally, the Paris Region Institute (IPR, Institut Paris Région, formerly IAU) claims that turning the ring road into an urban boulevard is too complex in the short term, for economic (cost of works) and logistical reasons (managing the transfer of traffic). The Institute instead proposed measures aimed at reducing speed on the boulevard, reducing the number of lone drivers and promoting public transport.

As part of the municipal campaign, political actors also addressed these issues. The City of Paris proposed to requalify the ring road as an urban boulevard by 2050, with quieter traffic, reserved lanes for carpooling, public transport and clean vehicles. The green party made similar proposals.

Meanwhile, the presidential majority proposed modulating the speed according to the time of day. While right-wing politicians overwhelmingly support the project of covering up the ring road in order to mitigate the urban disruption created by the infrastructure and to allow the construction of housing, some elected officials from the MODEM party have called for a closure of some of the ring road’s gates.

Gaspard Gantzer is the only candidate to call for totally removing the ring road, in addition to developing bike lanes all across the Greater Paris area.

Panorama of proposals for the ring road

After analyzing the data from the 2010 Global Transport Survey (EGT, Enquête Globale Transport), three main type of trips on the ring road were identified.

Short journeys that allow people to reach neighboring or nearby municipalities; the main areas in this regard are the north-east of Paris, between Montreuil, Pantin, Le Pré-Saint-Gervais and the 20th arrondissement. These are the least numerous overall due to the presence of alternate roads or modal alternatives (tramway, RER). The second type of trip is the most common: the “bypass trip” which people make to reach a destination on the opposite side of Paris; for example, it can be a journey between the 15th and 17th arrondissements. Finally, long trips, which connect urban poles located on the outskirts (Roissy-en-France, Versailles, Chessy, Nanterre, etc.).

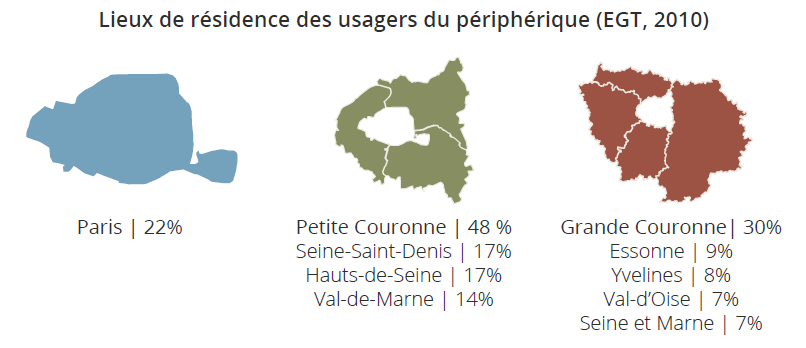

In 2010, only 20% of people using the ring road lived in Paris. Nearly 80% live in the other departments of Ile-de-France. Half of all users of the ring road live in the inner suburbs (called petite couronne, i.e. the first ring of suburbs around Paris). They constitute the main starting point (47%) and main destination (48%) of all trips using the ring road. Furthermore, a quarter of all trips using the ring road start and end within these inner suburbs.

Place of residence of the users of the ring road (EGT, 210)

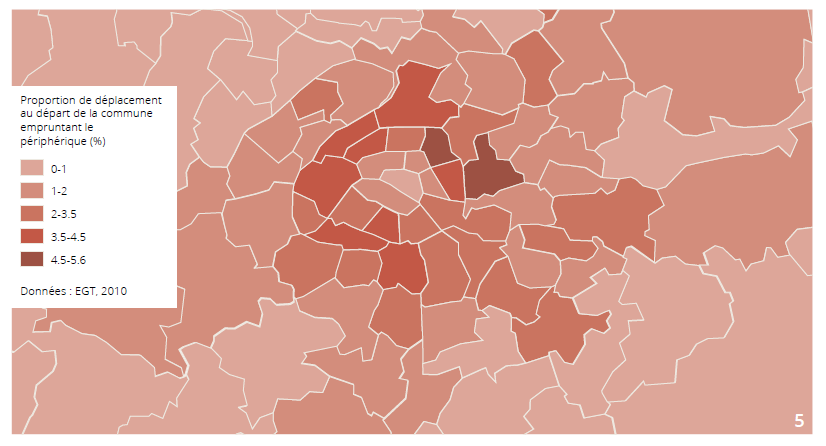

The most dependent areas on the ring road are the those that border it, both inside or outside Paris’ city limits; this is particularly the case for the north-east of Paris (19th arrondissement, Montreuil, Bagnolet, Romainville): most journeys using the ring road originate from one of these areas. The ring road is however far less important for trips originating in the outer suburbs (less than 1% of trips that originate in the outer suburbs use it).

Proportion of trips using the ring road, starting in a town or arrondissement

In addition to analyzing the Global Transport Survey data, the students developed a tool for modeling journeys in Ile-de-France using Google Maps. When requesting from Google Maps an itinerary originating or ending in Paris or neighboring towns, the app overwhelmingly suggests taking the ring road, confirming that Paris and its inner suburbs depend most heavily on it.

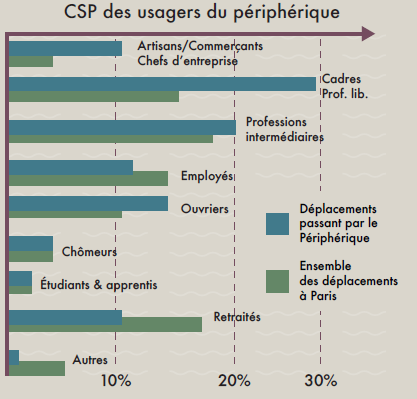

Three-quarters of all drivers on the ring road are men. Furthermore, the most advantaged socio-professional categories (executives and higher intellectual professions) and intermediate occupations (artisans/traders/business leaders) are over-represented among users. This is also the case for manual workers who make longer journeys (67 minutes on average) than executives (51 minutes on average), with the latter tending to make short trips (sometimes bypass trips) between arrondissements in Paris and/or the neighboring suburbs; indeed, analyzing their trips reveals a clear triangle linking the 15th and 16th arrondissements in the south, La Défense in the west and the 17th arrondissement in the north. Meanwhile, manual workers make trips that are more spatially spread out, originating mainly in northern and eastern suburbs and going to more distant poles (Créteil, the 16th arrondissement, Clichy, etc.). These results confirm the overall dynamics of Paris’ metropolitan area, with workers residing in the north and east and executives living in the west closer to their workplace.

Socioprofessional category of ring road users

Twenty semi-structured interviews were conducted with people who use or live near the ring road. Several user-profiles emerged: a mobile worker who depends on the ring road; an executive living in the outer suburbs; an executive living in the inner suburbs; a worker/employee; and a student living near the ring road. The majority of surveyed users take the ring road to commute or for work trips. While they are aware of the nuisances associated with the use of the ring road, they are rather against removing it as this would force some to give up using their car or, for others, to take longer routes. Only those living near the ring road but who don’t use it are in favor of removing it. Most respondents stressed the need to strengthen the public transport system before thinking about closing the ring road.

The students organized a workshop bringing together about twenty participants who put themselves in the shoes of typical users of the ring road to imagine how lifestyles would be reconfigured if it was removed, by mobilizing three models of action: increased accessibility, proximity and reinventing car-use. In the first model, the accessibility and performance of public transport was improved to encourage a massive shift from cars to public transport. In the second model, the participants imagined a reconfiguration of the urban landscape allowing for greater proximity between homes and workplaces and, consequently, a reduced use of cars. The third model – reinventing cars – imagined more car sharing to reduce the number of vehicles in circulation and allow a phasing out of the ring road by curbing the resulting congestion that would happen in the surrounding areas.

To reach the point of closing the ring road, the workshop participants imagined the gradual implementation of various measures. In the short term, they proposed measures such as lowering the authorized speed on the ring road or encouraging carpooling, pending the generalization of telework through greater pressure on companies to be responsible. Meanwhile, they imagined a network of bicyle lanes across the Ile-de-France region, the RER-Vélo, to promote modal shift and provide a comfortable alternative to cars for users who don’t travel very long distances. In the medium term, considering that most trips on the ring road are between locations in the inner suburbs, such trips could be transferred to public transport by optimizing the existing network or by resorting to the future Grand Paris Express; public transport would be fully automated and free. In the long term, the workshop participants imagined an urban exodus from Paris itself to the rest of the territory; they drew up a territorial model based on bioregions where the inhabitants carry out their activities within a 15-minute radius, calling for an evolution of the prevailing land planning model in order to promote more localized lifestyles.

Although the users of the ring road who were interviewed by the students were initially reluctant to see the ring road being removed, the study allowed us to imagine a future without the ring road that meets the aspirations of people living in and around Paris for more localized and slower-paced lives. For such a radical measure to be accepted, however, would require a gradual implementation, over a long period of time and in consultation with the inhabitants, of ambitious policies that aim to get away from an all-car model and promote a land-use planning that enables the transition to more sustainable and desirable lifestyles.

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xCar sharing is the pooling of one or several vehicles for different trips at different times. Three types of car sharing exist: commercial car sharing, peer-to-peer car sharing and “informal” sharing between individuals.

En savoir plus xTo cite this publication :

Professional Workshop Urban Planning and Development et Jean Debrie (07 February 2020), « Removing Paris’ périphérique ring road: towards more sustainable and desirable lifestyles? », Préparer la transition mobilitaire. Consulté le 18 May 2025, URL: https://forumviesmobiles.org/en/project/13215/removing-paris-peripherique-ring-road-towards-more-sustainable-and-desirable-lifestyles

Projects by Forum Vies Mobiles are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 France License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at contact.

Other publications