27 september 2021

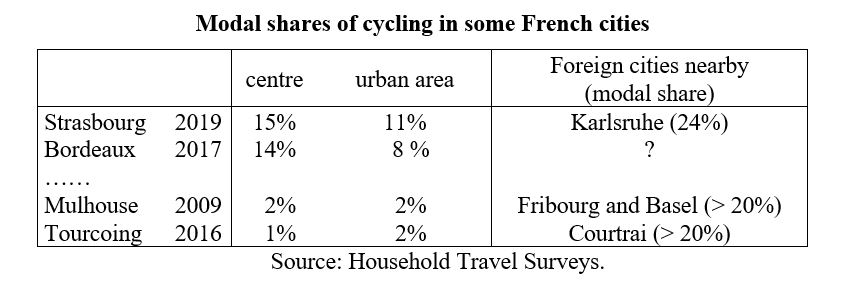

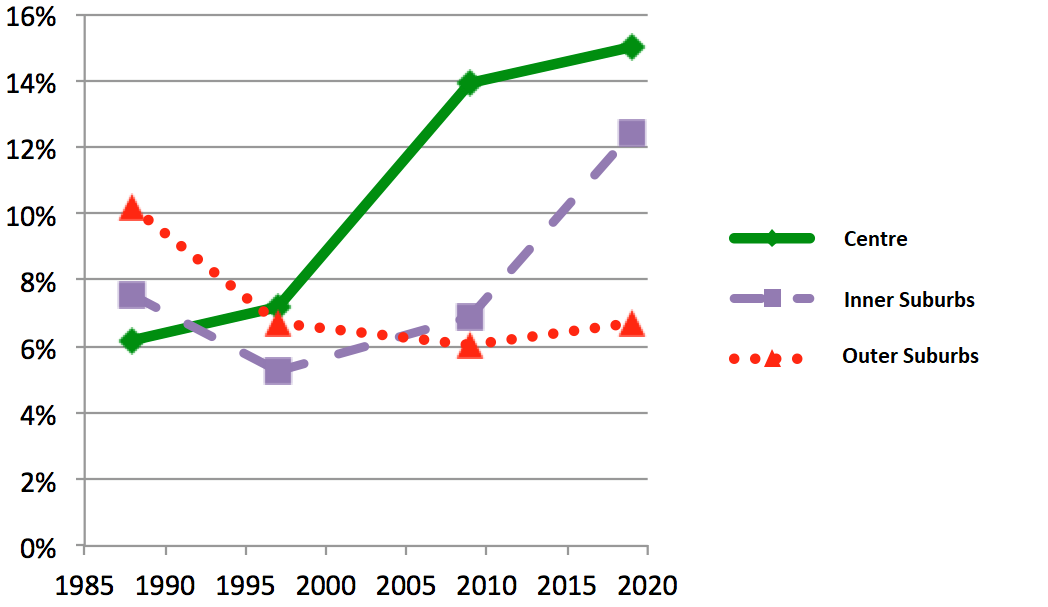

Strasbourg is the leading bicycle city in France and a constant source of inspiration for all French cities that want to promote cycling. With a modal share of 11% for the Metropolis and 15% in the city centre, it remains however somewhat below Europe’s leading cycling cities, but still ahead of Bordeaux or Grenoble, two cities which are progressing rapidly. How has the Strasbourg bicycle system developed? And can it serve as a model for other French cities?

In France, Strasbourg keeps implementing more and more bike-friendly innovations, most often by drawing inspiration from the best practices in foreign countries. Yet it’s worth dispelling one common misconception from the get-go: if Strasbourg has become so bike-friendly, it isn’t because of its proximity to Germany or especially to the city of Karlsruhe where cycling enjoys a modal share of 24%. In Bordeaux, for instance, where bicycle travel keeps growing, it would be hard to argue for any German influence. Meanwhile, Mulhouse, which is close to the very bike-friendly cities of Basel and Fribourg, only has a modest modal share of 2%, while Tourcoing, which is only 12 km from Courtrai, only has a modal share of 1%. We will therefore have to abandon this simplistic culturalist approach in order to explain Strasbourg’s evolution. After presenting the context, we will discuss some of the steps that facilitated the development of cycling, before introducing the measures that allowed for the development of a bicycle system.

In the post-war years, Strasbourg wasn’t much different from other major French cities.

Strasbourg is today a city of 285,000 inhabitants. The metropolis has 505,000 inhabitants and an urban area of 785,000 inhabitants. Enclosed in its historic fortifications until the end of the 19th century, the inherited city is very dense. Suburbanisation extended the urban growth in the near periphery until the middle of the 20th century. Social housing estates were hastily built on the outskirts, from the 1950s to the 1970s. Since then, residential areas have greatly expanded the villages in the periphery. The urban area’s expansion is limited to the east by the Rhine and its port, and is located in the highly dense Plain of Alsace (400 inhabitants/km2).

The city is almost entirely flat (with some hillsides to the west) and has many rivers and canals. In 1968, together with some other large cities, it established and became part of an urban community (the CUS, Communauté Urbaine de Strasbourg) and, from the outset, became responsible for transport, thus helping it construct a coherent policy in this domain. An urban planning agency was created in the process to assist this (later named ADEUS – Agency for the development and urban planning of the Strasbourg agglomeration).

To cope with the very rapid growth of motorisation, as in all major French cities, the French government took two major initiatives.

1/ From the 1950s, it designed a spider-web motorway network around the city, to "preserve the centre" by keeping cars away, while facilitating access to it. This network is now almost complete, except in the east, as the Autonomous Port has always refused to sell its land. As a result, a very congested motorway (the A35) bypasses the city centre to the west, less than a kilometre from the cathedral, on what was supposed to remain a green belt (see Figure 1). Today, and despite strong opposition, the Great Western Bypass is under construction, always with the argument of preserving the centre.

2/ In 1971, the government drew up a traffic plan that established one-way traffic on main roads, coordinated junctions with traffic lights and created off-street parking facilities. As a result, two main roads traverse the city centre, one going north-to-south (50,000 vehicles per day) and one going east-to-west (30,000 vehicles per day).

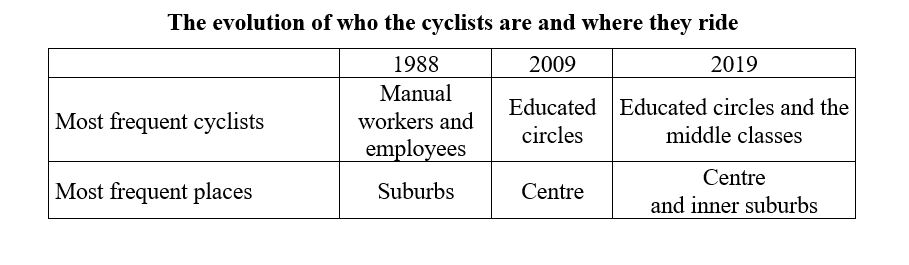

Consequently, just like everywhere else in France and even in Europe, throughout the 1960s and 1970s cycling was in free fall. But despite this unfavourable context, Strasbourg managed to save cycling from disappearing altogether, thanks to a mix of fortuitous circumstances and deliberate initiatives in which a few individuals, who deserve mentioning, played a prominent role.

Figure 1. Map of Strasbourg’s city centre. Source: https://www.mystrasbourg.com/data/img_1610447383.jpgThe three decades from the 1970s to the 1990s were crucial for the future of cycling in Strasbourg and are worth recounting.

In the early 1970s, the government realised that cars would never be able to cover all trips people needed to make and that it would have to reinvest in public transport. Because Strasbourg couldn’t afford to build a metro, in 1975 it opted for constructing a tramway. But the old tram system was only decommissioned in 1960, 12 years earlier. And building a tram means shutting down traffic through the city centre. Strasbourg was hesitant. In 1983, a pro-car mayor was elected, and in 1986, the city decided to build a metro, but construction was delayed to avoid works during the 1989 elections.

Meanwhile, the city didn’t invest much in its public transport: buses were getting old, they kept getting stuck in traffic, and were few and far between in the evenings and in the outskirts. Due to this lack of public transport, many residents of Strasbourg kept their bicycles. Especially students whose population rapidly increased, with their campus being built near the city centre, on former military grounds (while in other cities, new university campuses were more generally being built on the outskirts).

Two pedestrian areas were established at that time: the Cathedral Square and surrounding streets, and the alleys of the Petite France area. The goal was to promote the city’s heritage, but the development of pedestrian streets also helped make cycling safer. Despite some initial reluctance and setbacks, local business owners were generally satisfied with them and ended up calling for more. Pedestrian streets continued to expand and today, they offer a vast network of quiet streets, except during pedestrian rush hours.

In 1969, following the death of a parishioner who was hit by a car while riding a Solex moped, a young pastor named Jean Chaumien devoted himself to defending "light two-wheelers." He regularly lobbied the mayor, Pierre Pflimlin (centre-right), who was known to be rather opposed to cars and didn’t have a driving licence. In 1975, he created CADR (Comité d'action deux-roues, the Two-Wheeler Action Committee). This organisation frequently carried out educational initiatives that kept the media and residents of Strasbourg interested in cycling.

In 1980, Chaumien founded the FUB (Fédération française des usagers de la bicyclette, the French Federation of Bicycle Users), whose headquarters are still in Strasbourg, then in 1983 took part in the creation of the ECF (the European Cyclists’ Federation).

With the energy crisis of 1974, as everywhere in Europe, the French government decided to promote cycling, but the priority at this time was to invest in public transport, which had been neglected for 30 years. Cycling benefited from national subsidies but these unfortunately only lasted two years (1978 and 1979) before drying up because of budget cuts linked to the second oil crisis, and then to decentralisation. Like several other cities in France (Grenoble, Lille, Bordeaux...), Strasbourg seized this opportunity to start drawing up a "bicycle master plan."

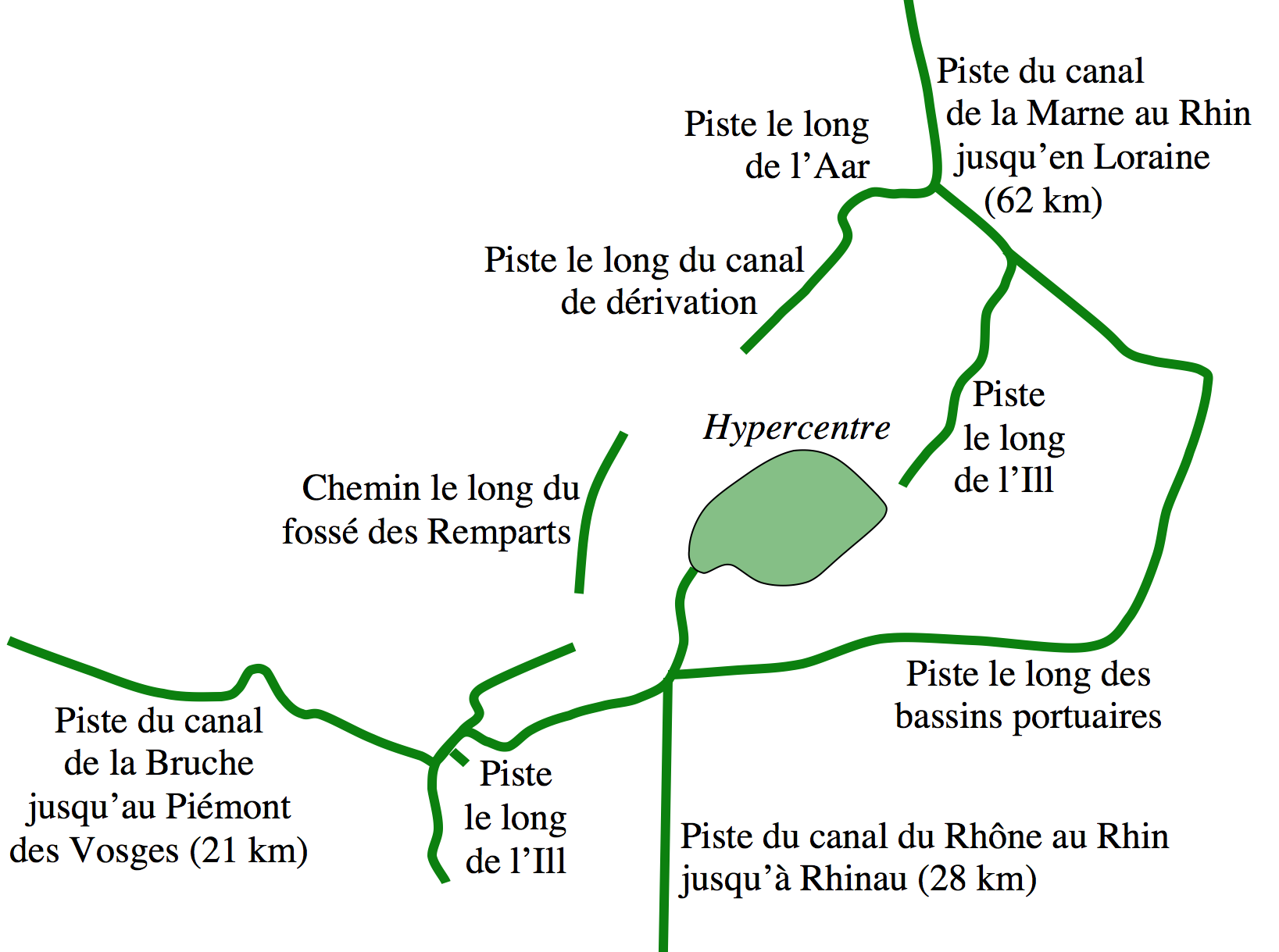

To inform their plan, Chaumien suggested to the mayor that they organize a trip to the Netherlands. In June 1978, along with the president of the Urban Planning Agency, the director of the DDE (Departmental Directorate of Equipment) 1, as well as some elected officials and local engineers, they travelled to The Hague where they were welcomed by the mayor. Pflimlin returned to Strasbourg convinced of the benefits of cycling and decided to build a network of bike paths, so long as they interfered as little as possible with car traffic. The plan was therefore mainly to establish bike paths along rivers and canals (see Figure 2), through the parks and forests of the urban community and on the widest sidewalks.

Figure 2. Cycling facilities along waterways. Scale: map width = 8 km. Map made by the author of this article.

Two-way cycling was widespread in the Netherlands as early as the late 1970s. Chaumien, who believed in their usefulness and safety, wanted to create some in Strasbourg. The city reluctantly agreed on the condition that they be removed if they led to any accidents. But no such issue ever occurred and twenty years later, three quarters of all two-way bike lanes in France were located in Strasbourg. Other cities tried to do the same until a national decree of 2008 renamed them two-way bike lanes and finally made them mandatory in one-way streets in 30 km/h zones.

Outside Paris, Strasbourg is France’s third busiest railway station (after Lyon and Lille) in terms of passenger numbers. Currently, 70,000 people arrive or leave by train every day, 90% of which travel on the TER (regional trains). In the 1970s and 1980s, some people were already in the habit of keeping a bike waiting for them upon arrival, which they then used to get around the city, and then parked near the station at night, on weekends and during holidays. From the 1980s, there was a bike parking facility near the station that could store about twenty bikes. Created by CADR, it wasn’t free of charge, but it was guarded and could carry out small repairs. Demand continued to grow and today 3,000 bicycles are routinely parked around the station, secured to open-air hoops or in bicycle parking facilities.

In March 1989, Catherine Trautmann (PS, socialist party) was elected mayor of Strasbourg. She advocated for a tramway, rather than a metro, in order to rid the city centre of cars. A student of Protestant theology (like Jean Chaumien) and a member of CADR, she defended humanist values, seeking to build a city for people rather than for cars. She therefore championed a coherent travel policy, aiming to reduce car traffic in favour of public transport, walking and cycling, which meant completely redeveloping the public space around tram lines. In November 1994, the first line was inaugurated and was a great success. Trautmann was easily re-elected in March 1995.

That year, for the first time in France, the urban community appointed a full-time “cycling officer”: Jean-Luc Marchal. A historian and journalist, and former member of CADR, he quickly understood that building cycling facilities wasn’t enough, and that it was also necessary to establish what would later be called a bicycle system 2, by developing as many initiatives as possible to strengthen the image and practice of cycling. He was efficiently supported in this goal by ADEUS, of which several members were in favour of cycling (notably Michel Messelis, an urban planner, and Daniel Hauser, a project manager).

This team designed a new "bicycle master plan," adopted in 1994, which aimed to develop cycling facilities throughout the city, including on major roads, by reassigning space previously used by cars if necessary.

Like all other modes of travel, cycling is a system with four components: a reliable mode, a sufficiently interconnected network, a competent user, and a set of common rules 3. Here is how a series of measures allowed for the development of each of these components.

Access to a bike - and one in good condition - is an essential prerequisite. The city offers a bike rental service – Vélhop – for variable durations (from one hour to one year), at a low price, limited in time and with the obligation to return the bike to the departure station. This solution has three advantages: 1/ it greatly reduces the cost of such a service to the community compared to a system of self-service bicycles like the Vélib' in Paris, 2/ it can offer a wide variety of bicycles: classic, electric, for children, delivery bicycles and tricycles, tandem bikes... and 3/ it encourages residents to choose a bike that is adapted to their needs. There are currently 6,500 bicycles available throughout the city in 20 automatic stations and 5 shops (or manned stations).

The city supports several bike self-repair workshops, some of which are mobile and travel to social housing estates and to various events. It also lends out several kinds of cargo bikes, for a maximum of one month, enough time to grasp the utility of these machines. The city also offers a financial incentive for the purchase of electric bicycles (or for retrofitting a traditional bicycle with an electric motor) and cargo bicycles, with the amount varying based on family income.

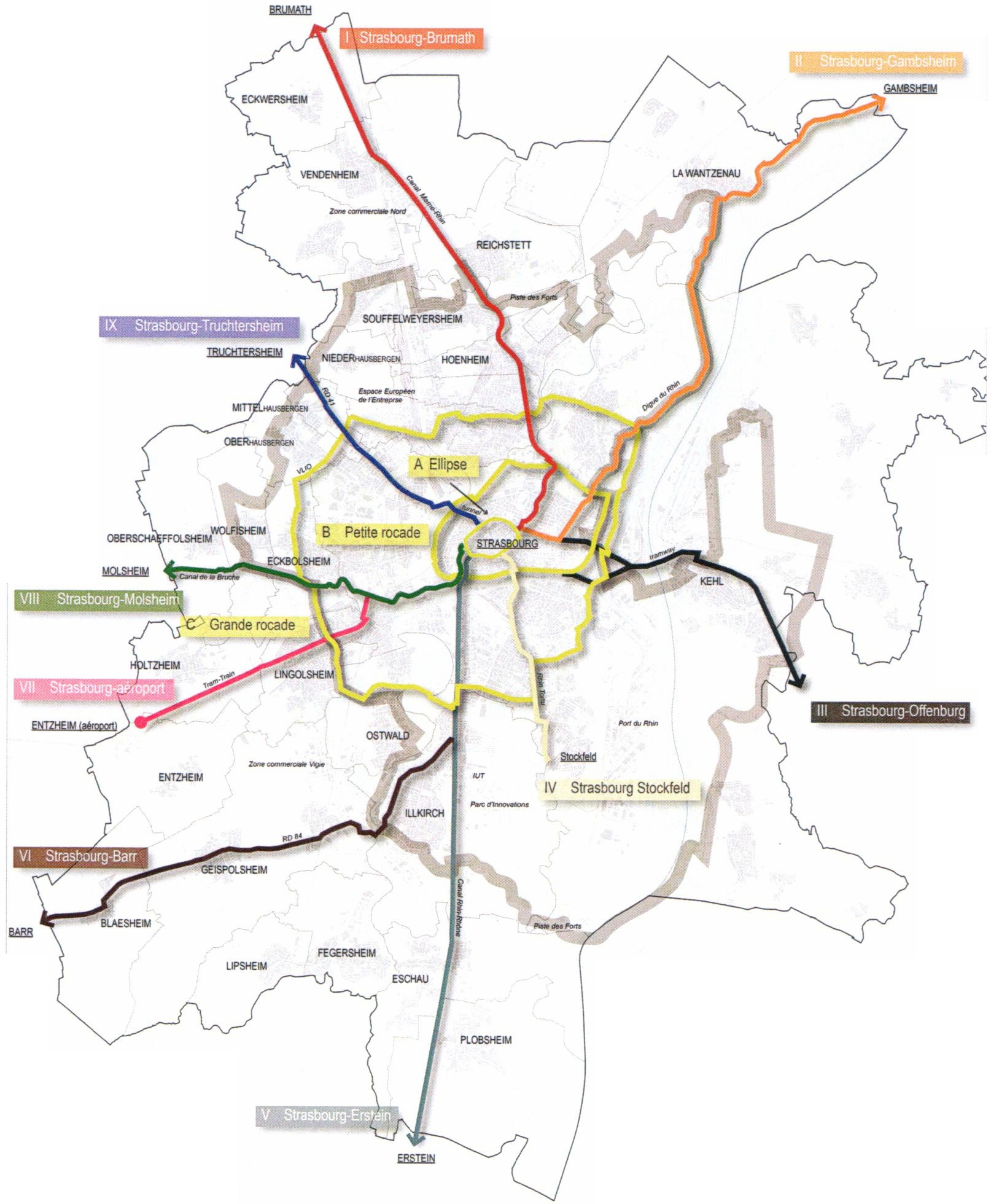

The goal isn’t only to increase the total number of cyclable kilometres, but also to calm car traffic on all networks, for the benefit of all modes as well as residents, by adding more 30 km/h zones and meeting areas, eliminating transit in neighbourhoods and in front of schools, turning four-lane roads into two-lane roads (such as with the Avenue des Vosges in 2019) to avoid setting up bike lanes on sidewalks 4, and even slowing down traffic on highways and urban expressways. The tramway extension (6 lines + now a bus with rapid transit) greatly contributes to calming traffic in the city. Since 2011 and the third bicycle master plan, the city has been trying to develop a structuring network of super bike paths (called Vélotras, see Figure 3), promoting long journeys, including in the outskirts. Recreational bike paths are also part of the plan, including the “Fort Trail” (85 km) that connects the old forts surrounding the city.

Figure 3. The Vélotras project, super bike paths. Source: ADEUS.

Secure parking reduces the risk of theft and promotes intermodality. Strasbourg built several large “bike-parks” where, for €40 per year, cyclists can be guaranteed a good quality of service: 350 places in the city centre, 1,600 places near the station. Strasbourg also increased the number of bike shelters near major public transport stations and set a mandatory minimum number of bike parking spots in new buildings.

Strasbourg has striven to make cycling attractive to newcomers by developing and supporting various services and initiatives (as reported in the 2019 Action Plan for Active Mobilities 5), such as a bicycle school for adults, training programs for schoolchildren, a hugely successful challenge called "Bike to work” (Au boulot à vélo, involving 382 companies and 11,000 employees in 2019), and specific actions aimed at underprivileged housing estates.

Strasbourg’s communication strategy is particularly innovative in trying to make cycling an essential part of its identity. At the start of the 1990s, it launched its slogan "Strasbourg, a bike ahead" (Strasbourg, un vélo d’avance). In 2000, the widely-read local newspaper Dernières Nouvelles d'Alsace published a sixteen-page supplement on cycling by CADR. In recent months, a new poster appeared around town, with the following slogan: "Bikes for social distancing." Since 1989, successive mayors and several of their deputies have regularly cycled through the city. CADR, fully supported by the urban community (which has since become a Metropolis), has taken part in countless events.

In 2012, City Councillor Dr. Feltz launched the concept of "prescription cycling." Patients with a prescription can use Vélhop bicycles for free for the duration prescribed by their doctor. This initiative has been widely commented on, even abroad, and its creator recently published a book called "Prescription Sport for Health" (Sport santé sur ordonnance).

In this domain too, Strasbourg has been a pioneer city in France. We have already mentioned two-way cycling. In the early 1990s, bus lanes were opened to cyclists (as in Rennes or Annecy). In 1996, mopeds were banned on bike paths, a provision that was adopted nationwide by decree in 1998. From 2012 to 2017, the city experimented with reduced fines for cyclists (50% reduction), to make them more acceptable but also more systematic. Cyclists are indeed much less dangerous to others than cars. But the scheme was eventually abandoned, under pressure from a new prosecutor who disliked the measure. In 2017, the city created the first “bikestreet” (vélorue) in France (rue de la Division Leclerc), a street where cyclists have right of way over motorists.

However, the relationship between cyclists and pedestrians remains a contentious issue. Due to its high density, Strasbourg is very busy, crowded with both pedestrians and cyclists, who often compete for space in its vast pedestrian zone. Some believe that cyclists should be banned from the pedestrian zone (like in Fribourg), while others claim that both will eventually cohabit peacefully, with both sides having to understand that bikes are silent.

If cycling has been so successful in Strasbourg, it is first and foremost thanks to a continuous cycling policy that began in 1978 and hasn’t stopped since 6. This success rests first on the determination of a dozen men and women who promoted cycling despite much opposition: in the 1980s, including in Strasbourg, cyclists were openly seen as a "minority group." Cycling in Strasbourg also benefitted from some favourable circumstances: the land is almost entirely flat, the high density means shorter travel distances 7, and public transport has historically been deficient.

Strasbourg has empirically discovered the value of a systemic approach to cycling, which not only leads to the construction of cycling facilities, but also fosters a "cycling culture" in all areas. Inspired by best practices throughout Europe, it has again and again experimented with original initiatives, some of which have failed, but which have always kept cycling in the news, as a modern, friendly, ecological, economic, user-friendly and democratic solution. The “cycling city” policy is more broadly part of a coherent urban travel policy that is progressing just as a fast as car traffic is slowing down 8.

However, many challenges remain: extending the network on the outskirts and completing the Vélotras (which is far from completion), relying less on the tramway system, removing 4-lane roads in the city and eliminating bike paths on sidewalks, dealing with gaps and interruptions in the cycling network, reducing the number of traffic light junctions, finally achieving a "30 km/h city" and getting underprivileged people to reconnect with bicycles 9.

Many ingredients of Strasbourg’s recipe for success are perfectly transferable to other French cities and many are inspired by them, even if there are – as always – local specificities that aren’t reproducible or require some adaptations.

FIgure 4. Modal share of bikes by place of residence. Perimeter: Urban Community of Strasbourg. Source: 1988, 1997, 2009 and 2019 household travel surveys.

1 Hubert Peigné, who later became interministerial coordinator for the development of cycling from 2006 to 2011.

2 Frédéric Héran, “The bicycle system”, Mobile Lives Forum’s dictionary.

3 Frédéric Héran, « Une analyse structurale des systèmes modaux », [A structural analysis of modal systems], Revue d'économie régionale et urbaine, n° 2, 2021, p. 225-245.

4 The city overused this solution and following a complaint from a pedestrians’ association, it was ordered by the Administrative Court in 2013 to properly delimit cycling and pedestrian spaces.

5 https://www.strasbourg.eu/documents/976405/1084289/0/b3fb3dac-3170-6921-a7c6-240844dd5b20

6 Only La Rochelle’s policy is older (since 1976) and it has enjoyed similar success.

7 In the Eurometropolis, 45% of internal trips are less than 1 km, 26% are 1 to 3 km, 14% are 3 to 5 km, 10% are 5 to 10 km and 5% are over 10 km (see Thimothé Kolmer (dir), Mobility Survey 2019. Essential, results, ADEUS, Strasbourg, 2019, p. 32). Therefore, 50% of internal travel is between 1 and 10 km, and would be possible by bicycle.

8 Frédéric Héran, « Vers des politiques de déplacements urbains plus cohérentes » [Towards more coherent policies in terms of urban mobility], Norois, n° 245, 2017, p. 89-100.

9 Cycling has remained more popular in Strasbourg than in other cities (especially Grenoble or Bordeaux), but it has still regressed a lot in social housing estates. Strasbourg strives to bring services to these areas: bike schools, Vélhop stations, mobile self-repair workshops...

The bicycle system refers to all the facilities, materials, services, regulations, information and skills involved in ensuring effective, comfortable, safe cycling practice in a given territory.

En savoir plus xFor the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xTheories

Other publications