Understanding the political economy of car dependence

Visuel

Transcription écrite

I’m Giulio Mattioli, a Research Fellow at TU Dortmund University, and I’m here to talk to you about a paper we recently published titled “The political economy of car dependence” with my colleagues Cameron Roberts, Julia Steinberger and Andrew Brown.

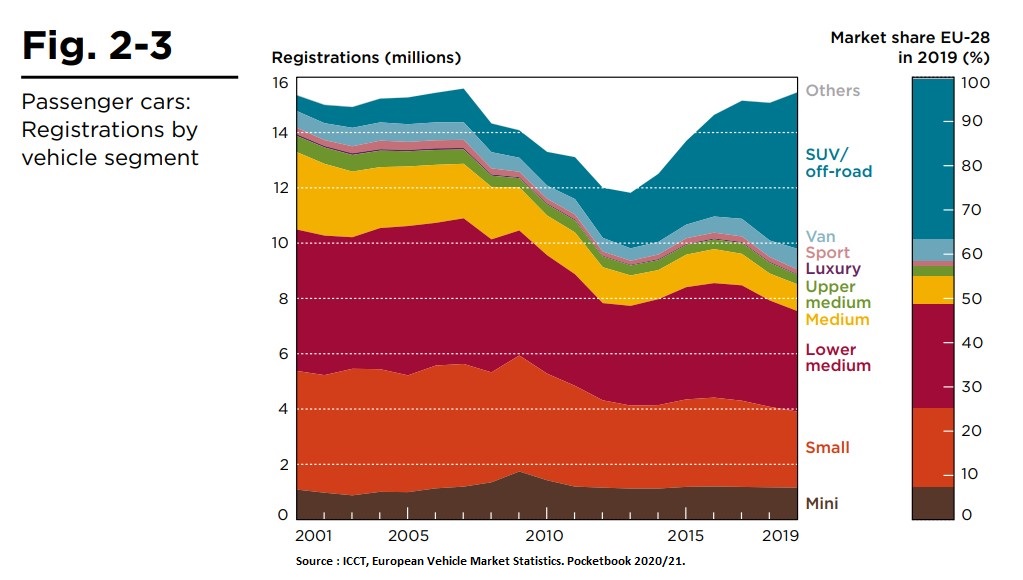

## The SUV boom

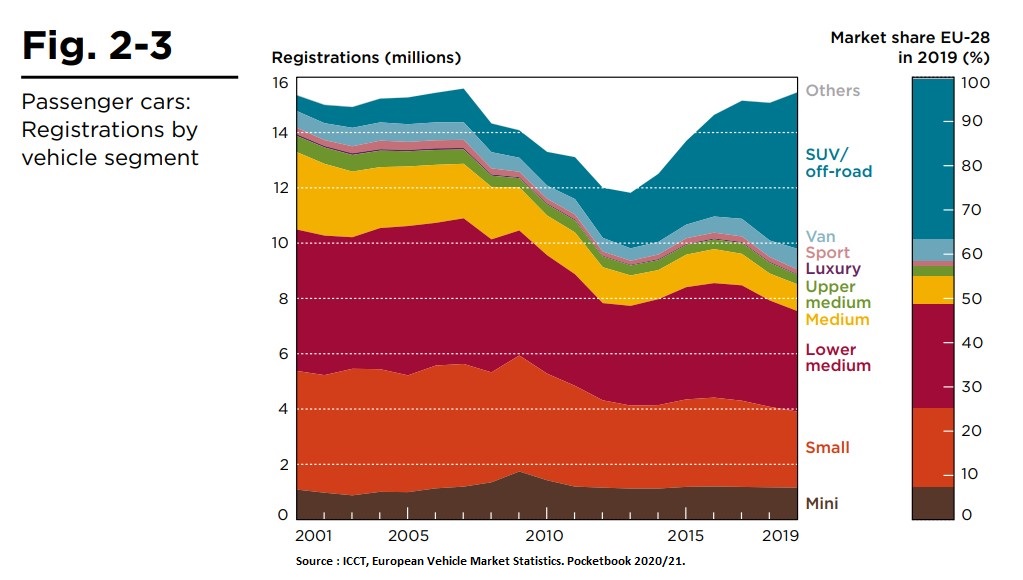

Before I get to that, I’d like to talk to you about the SUV boom which has very much been in the news, and it’s in some ways an illustration of the political economy of car dependence. So how do we explain that there’s an SUV boom in the European market? One needs to look both at the demand and the supply side.

The demand side is often emphasized by common interpretations, for example, by International Energy Agency, or by the media where it’s often argued that it’s a question of consumer taste and preferences - consumers have discovered a love for SUVs.

There certainly seems to be a latent demand for these vehicles and we don’t really know why that is. There are several explanations, more or less plausible regarding for example fashion, regarding the convenience of those larger vehicles, for people who have back problems, older people and so on. But also by the fact that these vehicles are perceived as safer, even though they are not necessarily safer, as they are more likely to roll over. But besides these reasons related to demand and consumer preferences and taste, there are also reasons on the supply side, and these are often neglected.

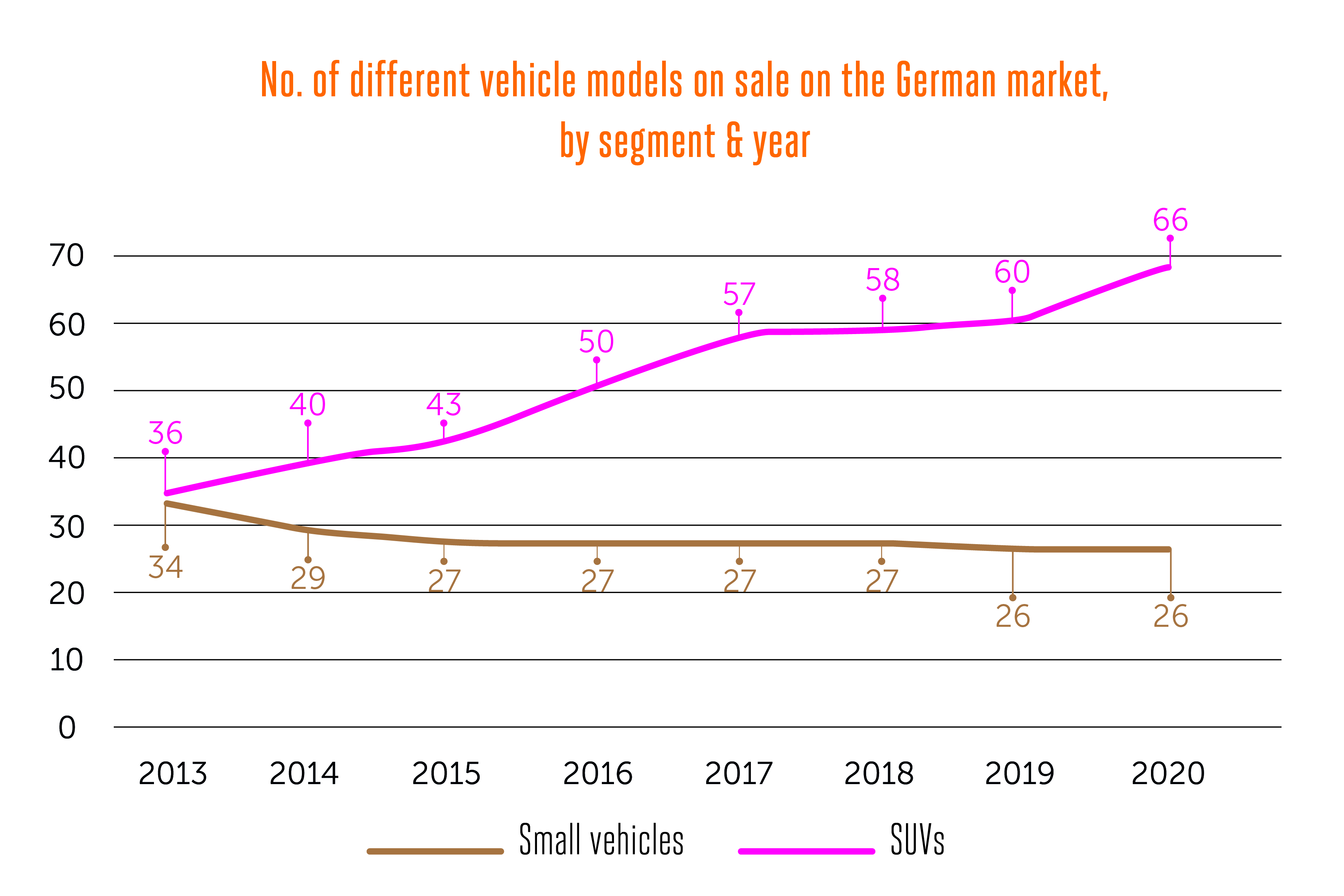

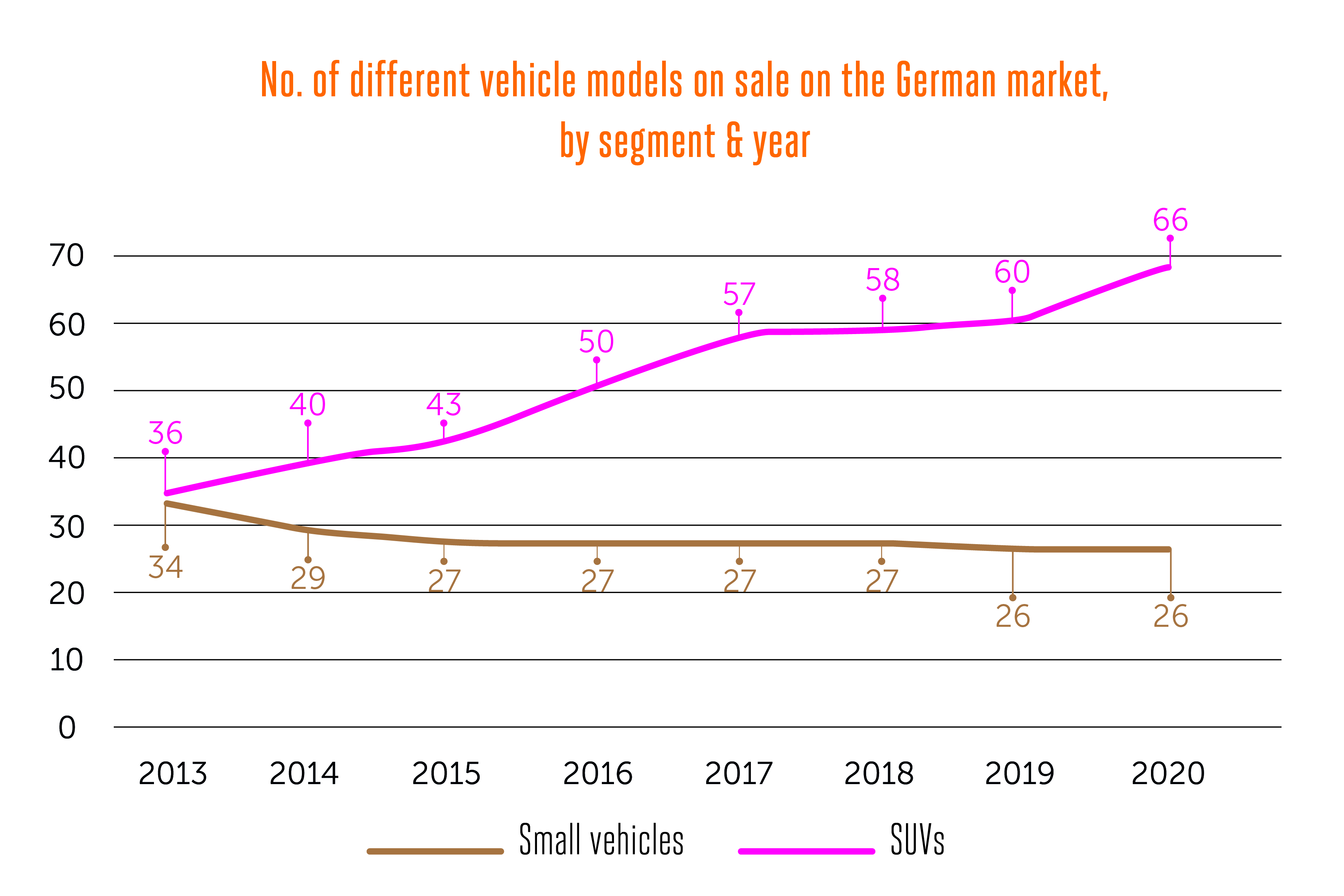

Car manufacturers seem to be able to extract a larger profit from these vehicles as compared to regular vehicles and that’s because SUVs are not much more expensive to make from a producers’ perspective - they’re just a bit taller, especially the new crossover models - but consumers perceive them as much more valuable and therefore they are willing to pay a much higher price on the market, and that tends to increase the profit margins for the auto makers which then obviously are keener to sell more and more of those vehicles with high profit margins as compared to other vehicles on which they make smaller margins. Then what happens is that an increasing number of models on the vehicle market - as we’ve seen in this graph for the German market - an increasing number of vehicles become SUVs and at the same time the producers tend to withdraw from the market other vehicles, such as small vehicles, as we see in this graph.

The demand side is often emphasized by common interpretations, for example, by International Energy Agency, or by the media where it’s often argued that it’s a question of consumer taste and preferences - consumers have discovered a love for SUVs.

There certainly seems to be a latent demand for these vehicles and we don’t really know why that is. There are several explanations, more or less plausible regarding for example fashion, regarding the convenience of those larger vehicles, for people who have back problems, older people and so on. But also by the fact that these vehicles are perceived as safer, even though they are not necessarily safer, as they are more likely to roll over. But besides these reasons related to demand and consumer preferences and taste, there are also reasons on the supply side, and these are often neglected.

Car manufacturers seem to be able to extract a larger profit from these vehicles as compared to regular vehicles and that’s because SUVs are not much more expensive to make from a producers’ perspective - they’re just a bit taller, especially the new crossover models - but consumers perceive them as much more valuable and therefore they are willing to pay a much higher price on the market, and that tends to increase the profit margins for the auto makers which then obviously are keener to sell more and more of those vehicles with high profit margins as compared to other vehicles on which they make smaller margins. Then what happens is that an increasing number of models on the vehicle market - as we’ve seen in this graph for the German market - an increasing number of vehicles become SUVs and at the same time the producers tend to withdraw from the market other vehicles, such as small vehicles, as we see in this graph.

The number of SUVs on the German market in 2020 was roughly double the one in 2013 while the number of small vehicles had declined during the same period. When that happens, it becomes more difficult for consumers to buy a non-SUV vehicle since so many of the vehicles on the market are SUVs. So that illustrates, demonstrates that you cannot understand this phenomenon by just looking at the consumer side and demand. You need to look at both consumption and production. This problem has deeper roots than just a change in taste and fashion. So you do need a broader and more systemic perspective to understand why these things happen.

## The political economy of car dependence

This was the motivation behind this review paper that we wrote about the political economy of car dependence. In some ways it was a reaction to much sustainable transport research and discourse on the part of activists which we found was too much focused on consumption at the expense of production, too much focus on win-win – so measures that will tick all boxes, all political goals and preferences - and too apolitical in that it tends to see sustainable transport as a technocratic endeavor. We argue by contrast that the fact that transport systems are car dominated is not just an oversight - something that happened despite our best intensions – but that the current car status quo is supported by powerful interests that have interest to make sure that things continue to be as car dominated as they are or become even more so in the future.

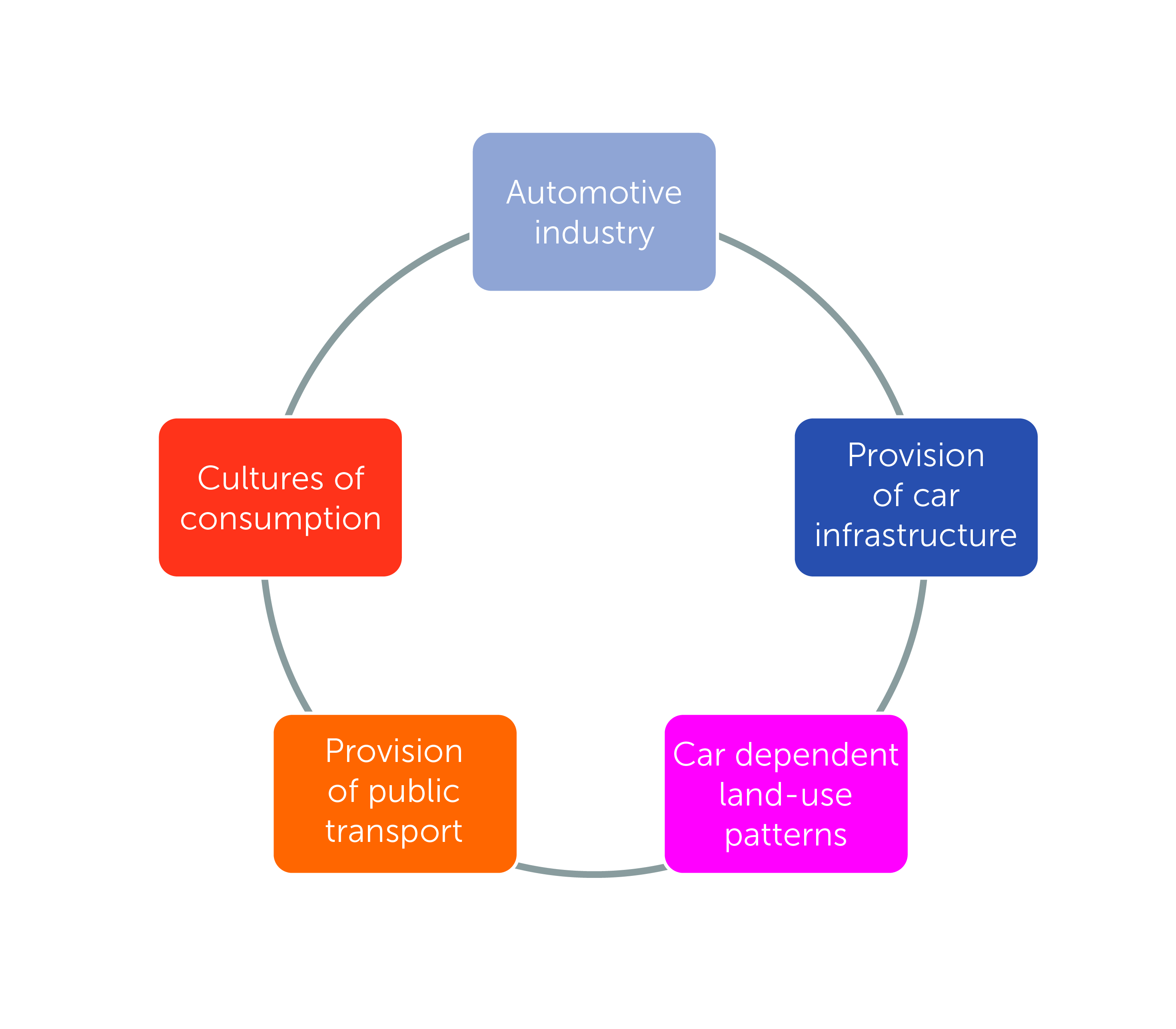

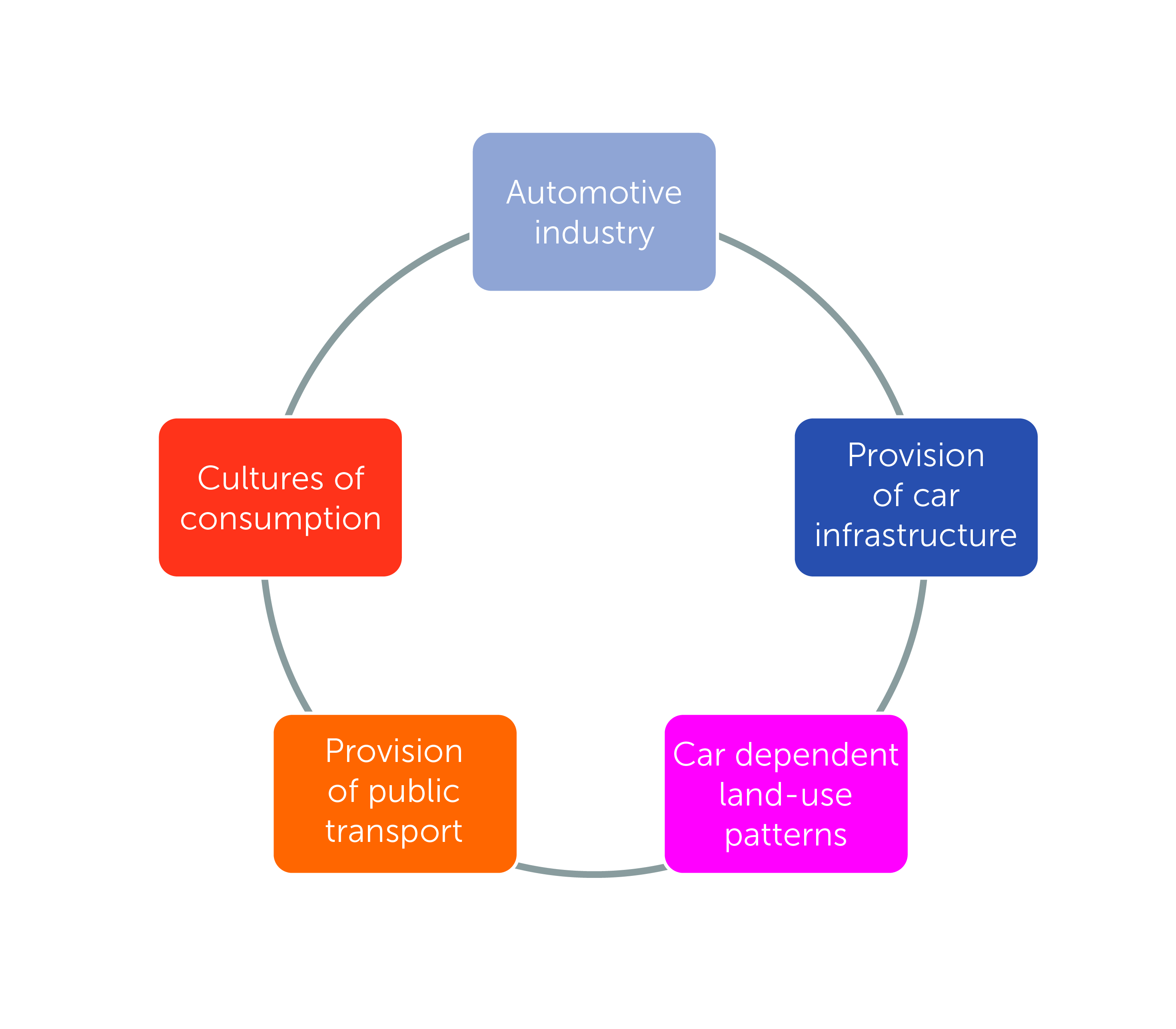

In this study, we identified 5 elements of the political economy of car dependence which you can see in this illustration.

The number of SUVs on the German market in 2020 was roughly double the one in 2013 while the number of small vehicles had declined during the same period. When that happens, it becomes more difficult for consumers to buy a non-SUV vehicle since so many of the vehicles on the market are SUVs. So that illustrates, demonstrates that you cannot understand this phenomenon by just looking at the consumer side and demand. You need to look at both consumption and production. This problem has deeper roots than just a change in taste and fashion. So you do need a broader and more systemic perspective to understand why these things happen.

## The political economy of car dependence

This was the motivation behind this review paper that we wrote about the political economy of car dependence. In some ways it was a reaction to much sustainable transport research and discourse on the part of activists which we found was too much focused on consumption at the expense of production, too much focus on win-win – so measures that will tick all boxes, all political goals and preferences - and too apolitical in that it tends to see sustainable transport as a technocratic endeavor. We argue by contrast that the fact that transport systems are car dominated is not just an oversight - something that happened despite our best intensions – but that the current car status quo is supported by powerful interests that have interest to make sure that things continue to be as car dominated as they are or become even more so in the future.

In this study, we identified 5 elements of the political economy of car dependence which you can see in this illustration.

And we looked at how they relate to each other, trying to cover both the production and consumption side. I will cover these briefly in this presentation starting from the car industry which is key in many respects.

## Understanding the car industry

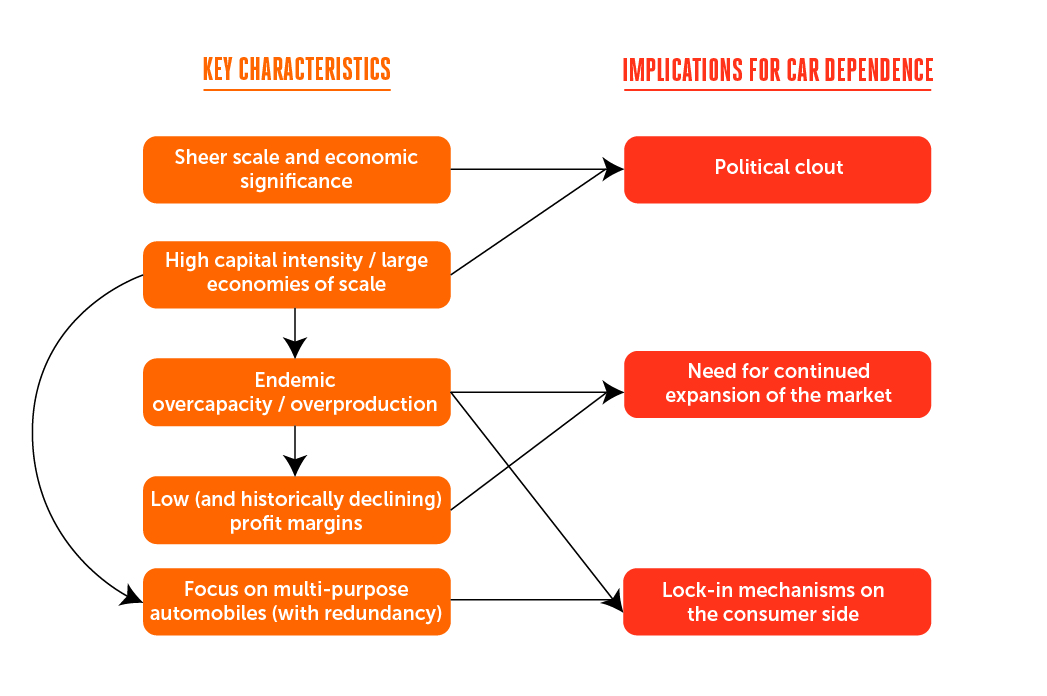

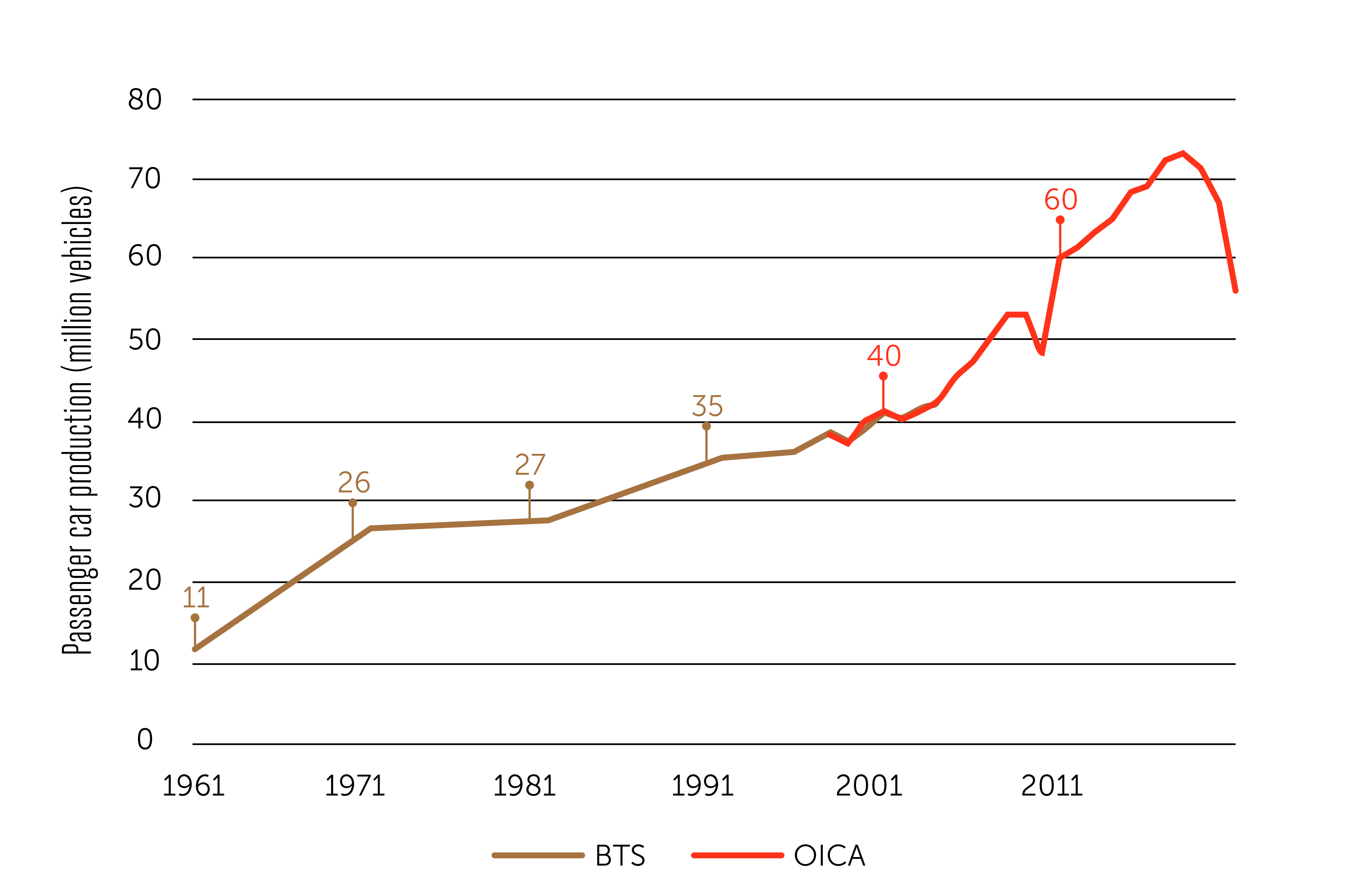

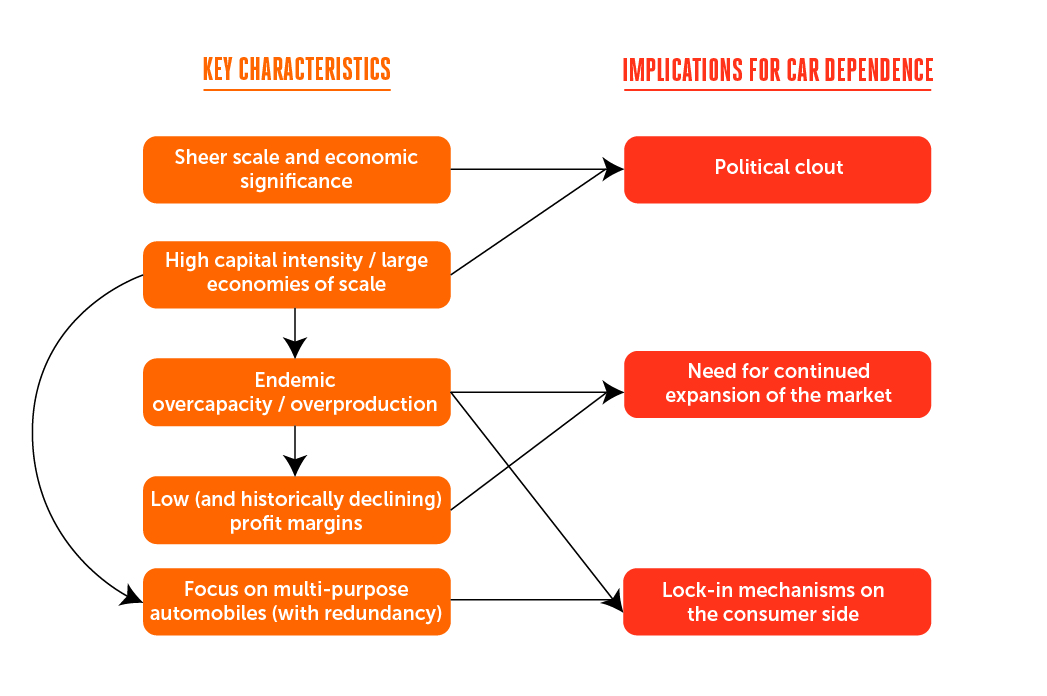

So if you want to understand how the car industry operates, there are a few key facts about it which we tried to summarize in this graph.

And we looked at how they relate to each other, trying to cover both the production and consumption side. I will cover these briefly in this presentation starting from the car industry which is key in many respects.

## Understanding the car industry

So if you want to understand how the car industry operates, there are a few key facts about it which we tried to summarize in this graph.

The key one is that the industry is characterized by very large economies of scale for reasons that have to do with steel production and all steel-body car productions and that tends to have several important implications, chief among them the fact that there are very high break-even points. A high volume of production is required to recover the capital expense. And when that is the case, that means that the industry needs to keep production levels very high and it cannot go very much below a certain rate of production otherwise it will lose money instead of making money. And that being the case, that means that the industry finds it difficult to cope with reductions in demand. So as soon as they have committed to a new large plant, they cannot then adjust production levels to slightly below what they have planned, because if they do so they will not recover their expenses.

So that makes it very difficult for them during an economic crisis when one of the first expenditures that households tend to cut is new cars. It’s very difficult for the industry to cope with this reduction in demand and so that’s why typically then the State jumps in and bails them out with taxpayers’ money. And another implication of economies of scale is that production tends to be concentrated in a small number of very large multinational firms which are then very powerful, but also concentrated in a small number of production sites where there are very large plants which, along with their suppliers, account for a lot of employment in certain regions for example in Europe.

And that means that when the automotive industry enters a crisis, that’s a very big problem for employment at the local level and that also tends to magnify the bargaining power of the automotive industry when it comes to negotiating bailouts and so on. Economies of scale also tend to explain why something happens which environmentalists tend to hate, but also not to understand, which is why we have very large vehicles - 5-seater vehicles which weigh tons - even though most of us use them for driving alone to work. And that’s a typical criticism on the part of environmentalists: that’s irrational wastefulness, why don’t we have smaller and lighter vehicles?

Well that might make sense if you want to optimize ecological efficiency, but from the industry perspective it very much makes sense to produce a lot of 5-seaters because these are suited to all kinds of uses: you can use them to go on holidays, to go to work, and so on. And you don’t need to have different vehicles for all these different purposes, and different people don’t need to have that many different vehicles. If you want to achieve economies of scale, it does make sense to have a general-purpose vehicle like that as the main one on the market.

The key one is that the industry is characterized by very large economies of scale for reasons that have to do with steel production and all steel-body car productions and that tends to have several important implications, chief among them the fact that there are very high break-even points. A high volume of production is required to recover the capital expense. And when that is the case, that means that the industry needs to keep production levels very high and it cannot go very much below a certain rate of production otherwise it will lose money instead of making money. And that being the case, that means that the industry finds it difficult to cope with reductions in demand. So as soon as they have committed to a new large plant, they cannot then adjust production levels to slightly below what they have planned, because if they do so they will not recover their expenses.

So that makes it very difficult for them during an economic crisis when one of the first expenditures that households tend to cut is new cars. It’s very difficult for the industry to cope with this reduction in demand and so that’s why typically then the State jumps in and bails them out with taxpayers’ money. And another implication of economies of scale is that production tends to be concentrated in a small number of very large multinational firms which are then very powerful, but also concentrated in a small number of production sites where there are very large plants which, along with their suppliers, account for a lot of employment in certain regions for example in Europe.

And that means that when the automotive industry enters a crisis, that’s a very big problem for employment at the local level and that also tends to magnify the bargaining power of the automotive industry when it comes to negotiating bailouts and so on. Economies of scale also tend to explain why something happens which environmentalists tend to hate, but also not to understand, which is why we have very large vehicles - 5-seater vehicles which weigh tons - even though most of us use them for driving alone to work. And that’s a typical criticism on the part of environmentalists: that’s irrational wastefulness, why don’t we have smaller and lighter vehicles?

Well that might make sense if you want to optimize ecological efficiency, but from the industry perspective it very much makes sense to produce a lot of 5-seaters because these are suited to all kinds of uses: you can use them to go on holidays, to go to work, and so on. And you don’t need to have different vehicles for all these different purposes, and different people don’t need to have that many different vehicles. If you want to achieve economies of scale, it does make sense to have a general-purpose vehicle like that as the main one on the market.

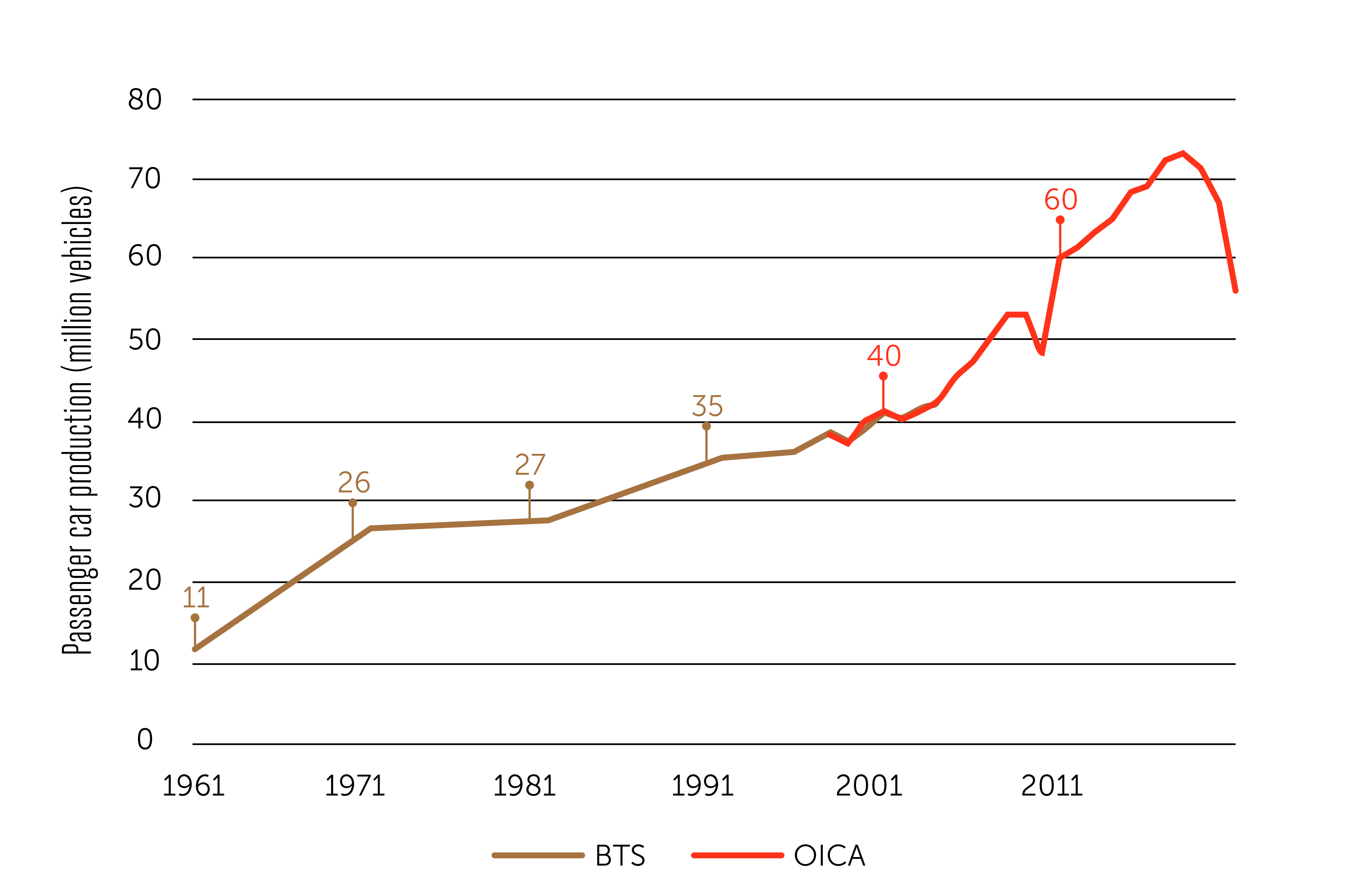

One of the key tendencies of the automotive industry is to push through as many vehicles as possible and that’s happened over the course of the twentieth century as we see in this graph, the number of vehicles produced per year has increased very rapidly up to very recently where it has declined mostly because of Covid but also because of saturation of the Chinese market and a shortage of superconductors probably, that’s what some people argue, we don’t really know - but we will see how long this reduction in car production will last. It might bounce back after Covid and certainly the long-term trend is towards increasing numbers of vehicles produced over time.

And as more and more vehicles are produced that creates a pressure on society to accommodate all these vehicles.

## Provision of car infrastructure

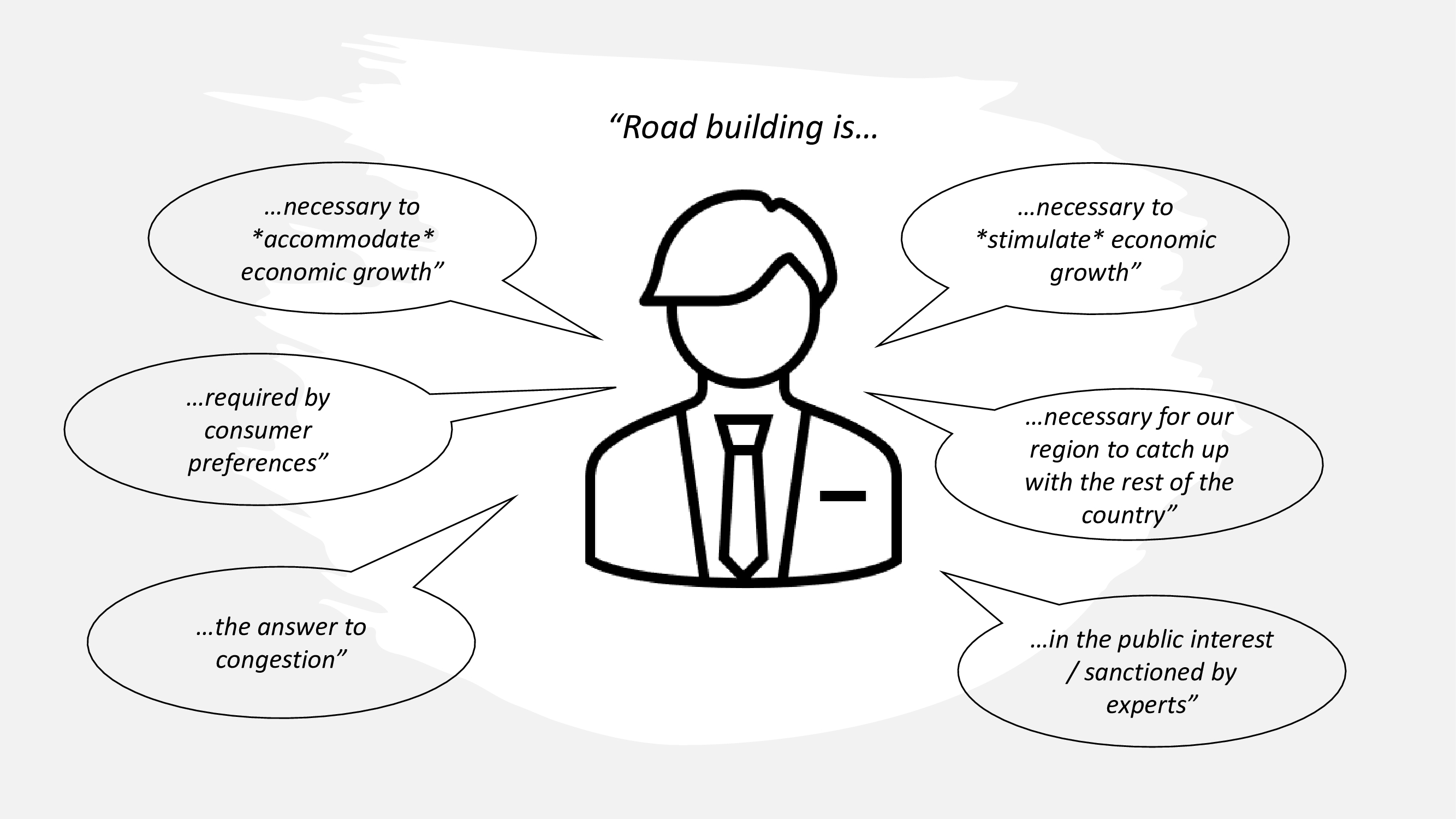

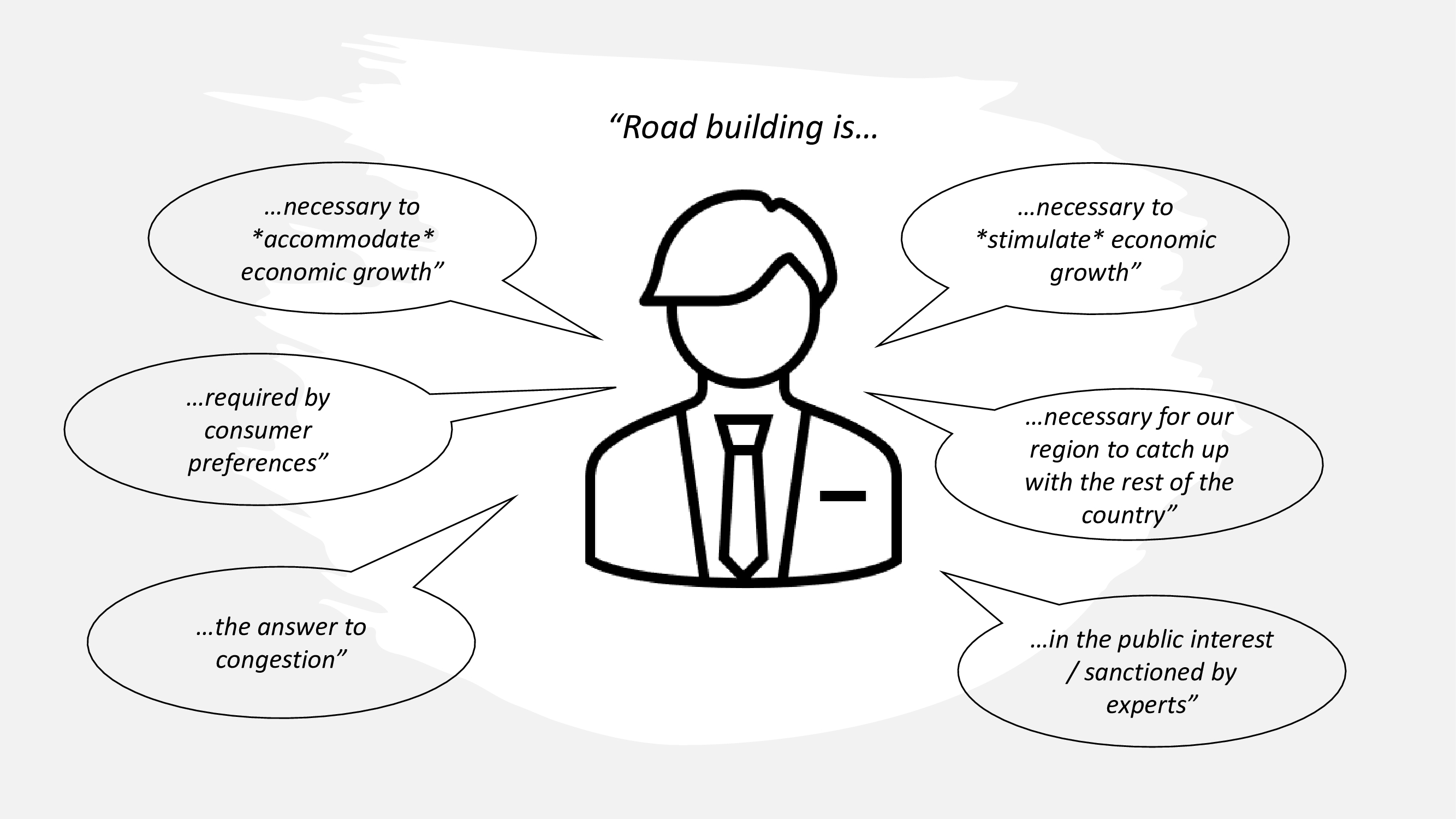

And the way in which that has happened brings us to the second point in our list which is car infrastructure and by that we mean roads and parking and all those kinds of things which accommodate vehicles in public space. This is where a lot of public money has gone into accommodating vehicles over the last decades, into expanding the road network and so on. Things like road building tend to be justified by policy makers in a variety of different ways which we’ve tried to summarize in this figure.

One of the key tendencies of the automotive industry is to push through as many vehicles as possible and that’s happened over the course of the twentieth century as we see in this graph, the number of vehicles produced per year has increased very rapidly up to very recently where it has declined mostly because of Covid but also because of saturation of the Chinese market and a shortage of superconductors probably, that’s what some people argue, we don’t really know - but we will see how long this reduction in car production will last. It might bounce back after Covid and certainly the long-term trend is towards increasing numbers of vehicles produced over time.

And as more and more vehicles are produced that creates a pressure on society to accommodate all these vehicles.

## Provision of car infrastructure

And the way in which that has happened brings us to the second point in our list which is car infrastructure and by that we mean roads and parking and all those kinds of things which accommodate vehicles in public space. This is where a lot of public money has gone into accommodating vehicles over the last decades, into expanding the road network and so on. Things like road building tend to be justified by policy makers in a variety of different ways which we’ve tried to summarize in this figure.

As we’ve seen here, there are very many different justifications there, partly contradictory, as for example when road building is justified as necessary to accommodate economic growth which results in increased traffic and congestion, whereby it is argued that we need to predict and provide in advance for these increases in traffic.

But it’s also sometimes argued that road building is necessary to stimulate economic growth, so basically, whether your economy is growing or not growing, you sort of always need road building from this perspective. And there are other ways less politically charged, less economically focused to justify road building, such as: it’s a way to accommodate consumer preferences; there are more left-wing ways to justify road building in terms of making sure that certain rural regions in particular can catch up with the rest of the country in economic terms; there are more technocratic ways of justifying that, as in for example because cost-benefit analysis has sanctioned that to be in the common interest; and so on. There are many different ways to justify road building and they tend to cover pretty much all of the political spectrum and other aspects as well, which makes any discourse that goes against road building marginalized. It almost doesn’t have any citizenship in the political debate.

## Car dependent land use patterns

A third factor related to car dependencies are car dependent land use patterns, often referred to as urban sprawl. That tends to be seen in the debate as something that has happened despite our best intentions, a form of planning oversight, an irrational and wasteful form of urban development that we should have known better than to implement. I suppose there’s some truth to that argument, but we argue in this paper that it’s not entirely an accidental outcome, that these land use patterns tend to prevail, because even though they are wasteful, they tend to maximize demand for certain goods, for certain industries such as the housing industry, which builds all those small houses in the periurban areas. Demand for road building, demand for oil, demand for cars and so on. So what we argue is that urban sprawl can also be seen as a form of stimulus, that the State encourages in order to create demand for a certain key industry, and it’s certainly been a form of stimulus at some point in History, in some countries.

## Provision of public transport

The next element that you need to consider in the political economy of car dependence, is public transport. It is often argued that public transport is impossible to provide in a convenient way when land use patterns are too car-oriented.

I suppose that’s true to some extent but it’s also not true in that you can provide decent public transport even in low density areas, but you do need to follow a certain approach which is called network planning, which requires public transport to be very much integrated and that you can only do if there is a rather strong public control on at least the planning of public transport. And that means that it’s not possible to provide competitive public transport in countries where public transport has been very much deregulated and privatized, such as for example in the UK, and that’s also a political economy factor that we need to take into account.

## The culture of car consumption

And last but not least in our list of elements of the political economy of car dependence comes the cultures of car consumption. We argue that of course consumers are attached to cars after decades of car dependence in many ways, they tend to perceive them as symbols of freedom, of social status, of masculinity sometimes, of independence for women. Also more recently as cocoons that protect you from a hostile urban environment. But mostly they tend to be seen nowadays as the normal thing to do, as something taken for granted. All of us who try to live without a car know that you sort of need to justify that choice with your peers, whereas you don’t need to justify the choice to buy one most of the time. So it tends to be very much entrenched in our culture nowadays. And this cultural aspect is important in explaining the SUV boom as consumers tend to perceive them as very aggressive cars, or powerful, cars that tell something about your social status and allow you to prevail in a competition with other drivers on the road.

## Four cross cutting characteristics of political car dependence

So to conclude, our analysis of the different elements of the political economy of car dependence leads us to identify 4 underlying and cross cutting characteristics of car-dependent transport system that sort of cut across these different elements. The first one being the role of social technical systems of provision which sounds very academic jargon but what it means basically is that you need to look at both social aspects and technical aspects, and both consumption and production, and that’s something that no discipline can do on its own, you do require a sort of interdisciplinary approach, a more systemic approach to capture the complexity of such a thing.

The second characteristic is what we call the opportunistic use of contradictory economic arguments, which we’ve seen for example in road building whereby both economic growth and economic decline are reasons to build roads. But you also see that with the car industry, which is simultaneously presented as a free-market champion but also in need of public bailouts every couple of years when demand goes down. And the third characteristic is perhaps the most important, it is the creation of an apolitical façade around car dependence and car decision-making and the current pro-car status quo, in that it is normalized, it is seen as taken for granted, and even though lots of public resources go into supporting it through hidden subsidies, that is seen as normal and almost not as a subsidy at all, whereas subsidies that go into competitors such as public transport tend to be questioned in terms of waste of public money and so on.

There are other manifestations of that such as when the domination that the car has over public space is seen as a normal thing to do and taking away a little bit of that space and giving it to other modes is seen as something radical, even though there is no reason when you think about it why so much space should go into providing space for a certain section of the population which owns and uses cars to the detriment of others who don’t. So this sort of apolitical façade creates a situation where it’s just seen as common sense to support this status quo and if you question it, you’re marginalized and portrayed as someone lacking common sense, as a hippie or as an authoritarian who wants to take away things from the population that are taken for granted.

The fourth and final characteristic is what we call the capture of the State by the car dependent transport system and here we refer to the fact that pro-car decision making is very much entrenched and very hard to dislodge and there are many reasons for that. One is lobbying of course, there are some powerful interests that lobby upon the State to do so. But it goes deeper than that in that there is something called State dependence, whereby the State is dependent on the automotive industry for income revenue, for employment and so on. So it doesn’t see its interests as different from those of the industry, and you see that particularly strongly in certain countries which have a particularly large and powerful automotive industry.

## Going beyond car dependence

So to conclude on a slightly more positive note, if I can, what lessons can we draw from this analysis in terms of how to go beyond car dependence and car dependent transport system? Two steps are necessary there in our opinion. The first one is a more cognitive one, it’s to see sustainable transport as more of a political endeavor, not as something technocratic that will appeal to all sides and all interests, but as something that is actively opposed by certain powerful interests that need to be named and identified otherwise there will be little chance to go beyond it.

Second, we would argue that since all these elements exist very much interconnected with one another, then a successful strategy to go beyond a car dependent transport system will need to tackle all of these elements at once. Because if you focus on just one or two of them, there are powerful synergies between them that tend to support the status quo. So one needs to have a bit more of a systemic and global vision of this problem than has perhaps been the case to date.

As we’ve seen here, there are very many different justifications there, partly contradictory, as for example when road building is justified as necessary to accommodate economic growth which results in increased traffic and congestion, whereby it is argued that we need to predict and provide in advance for these increases in traffic.

But it’s also sometimes argued that road building is necessary to stimulate economic growth, so basically, whether your economy is growing or not growing, you sort of always need road building from this perspective. And there are other ways less politically charged, less economically focused to justify road building, such as: it’s a way to accommodate consumer preferences; there are more left-wing ways to justify road building in terms of making sure that certain rural regions in particular can catch up with the rest of the country in economic terms; there are more technocratic ways of justifying that, as in for example because cost-benefit analysis has sanctioned that to be in the common interest; and so on. There are many different ways to justify road building and they tend to cover pretty much all of the political spectrum and other aspects as well, which makes any discourse that goes against road building marginalized. It almost doesn’t have any citizenship in the political debate.

## Car dependent land use patterns

A third factor related to car dependencies are car dependent land use patterns, often referred to as urban sprawl. That tends to be seen in the debate as something that has happened despite our best intentions, a form of planning oversight, an irrational and wasteful form of urban development that we should have known better than to implement. I suppose there’s some truth to that argument, but we argue in this paper that it’s not entirely an accidental outcome, that these land use patterns tend to prevail, because even though they are wasteful, they tend to maximize demand for certain goods, for certain industries such as the housing industry, which builds all those small houses in the periurban areas. Demand for road building, demand for oil, demand for cars and so on. So what we argue is that urban sprawl can also be seen as a form of stimulus, that the State encourages in order to create demand for a certain key industry, and it’s certainly been a form of stimulus at some point in History, in some countries.

## Provision of public transport

The next element that you need to consider in the political economy of car dependence, is public transport. It is often argued that public transport is impossible to provide in a convenient way when land use patterns are too car-oriented.

I suppose that’s true to some extent but it’s also not true in that you can provide decent public transport even in low density areas, but you do need to follow a certain approach which is called network planning, which requires public transport to be very much integrated and that you can only do if there is a rather strong public control on at least the planning of public transport. And that means that it’s not possible to provide competitive public transport in countries where public transport has been very much deregulated and privatized, such as for example in the UK, and that’s also a political economy factor that we need to take into account.

## The culture of car consumption

And last but not least in our list of elements of the political economy of car dependence comes the cultures of car consumption. We argue that of course consumers are attached to cars after decades of car dependence in many ways, they tend to perceive them as symbols of freedom, of social status, of masculinity sometimes, of independence for women. Also more recently as cocoons that protect you from a hostile urban environment. But mostly they tend to be seen nowadays as the normal thing to do, as something taken for granted. All of us who try to live without a car know that you sort of need to justify that choice with your peers, whereas you don’t need to justify the choice to buy one most of the time. So it tends to be very much entrenched in our culture nowadays. And this cultural aspect is important in explaining the SUV boom as consumers tend to perceive them as very aggressive cars, or powerful, cars that tell something about your social status and allow you to prevail in a competition with other drivers on the road.

## Four cross cutting characteristics of political car dependence

So to conclude, our analysis of the different elements of the political economy of car dependence leads us to identify 4 underlying and cross cutting characteristics of car-dependent transport system that sort of cut across these different elements. The first one being the role of social technical systems of provision which sounds very academic jargon but what it means basically is that you need to look at both social aspects and technical aspects, and both consumption and production, and that’s something that no discipline can do on its own, you do require a sort of interdisciplinary approach, a more systemic approach to capture the complexity of such a thing.

The second characteristic is what we call the opportunistic use of contradictory economic arguments, which we’ve seen for example in road building whereby both economic growth and economic decline are reasons to build roads. But you also see that with the car industry, which is simultaneously presented as a free-market champion but also in need of public bailouts every couple of years when demand goes down. And the third characteristic is perhaps the most important, it is the creation of an apolitical façade around car dependence and car decision-making and the current pro-car status quo, in that it is normalized, it is seen as taken for granted, and even though lots of public resources go into supporting it through hidden subsidies, that is seen as normal and almost not as a subsidy at all, whereas subsidies that go into competitors such as public transport tend to be questioned in terms of waste of public money and so on.

There are other manifestations of that such as when the domination that the car has over public space is seen as a normal thing to do and taking away a little bit of that space and giving it to other modes is seen as something radical, even though there is no reason when you think about it why so much space should go into providing space for a certain section of the population which owns and uses cars to the detriment of others who don’t. So this sort of apolitical façade creates a situation where it’s just seen as common sense to support this status quo and if you question it, you’re marginalized and portrayed as someone lacking common sense, as a hippie or as an authoritarian who wants to take away things from the population that are taken for granted.

The fourth and final characteristic is what we call the capture of the State by the car dependent transport system and here we refer to the fact that pro-car decision making is very much entrenched and very hard to dislodge and there are many reasons for that. One is lobbying of course, there are some powerful interests that lobby upon the State to do so. But it goes deeper than that in that there is something called State dependence, whereby the State is dependent on the automotive industry for income revenue, for employment and so on. So it doesn’t see its interests as different from those of the industry, and you see that particularly strongly in certain countries which have a particularly large and powerful automotive industry.

## Going beyond car dependence

So to conclude on a slightly more positive note, if I can, what lessons can we draw from this analysis in terms of how to go beyond car dependence and car dependent transport system? Two steps are necessary there in our opinion. The first one is a more cognitive one, it’s to see sustainable transport as more of a political endeavor, not as something technocratic that will appeal to all sides and all interests, but as something that is actively opposed by certain powerful interests that need to be named and identified otherwise there will be little chance to go beyond it.

Second, we would argue that since all these elements exist very much interconnected with one another, then a successful strategy to go beyond a car dependent transport system will need to tackle all of these elements at once. Because if you focus on just one or two of them, there are powerful synergies between them that tend to support the status quo. So one needs to have a bit more of a systemic and global vision of this problem than has perhaps been the case to date.

The demand side is often emphasized by common interpretations, for example, by International Energy Agency, or by the media where it’s often argued that it’s a question of consumer taste and preferences - consumers have discovered a love for SUVs.

There certainly seems to be a latent demand for these vehicles and we don’t really know why that is. There are several explanations, more or less plausible regarding for example fashion, regarding the convenience of those larger vehicles, for people who have back problems, older people and so on. But also by the fact that these vehicles are perceived as safer, even though they are not necessarily safer, as they are more likely to roll over. But besides these reasons related to demand and consumer preferences and taste, there are also reasons on the supply side, and these are often neglected.

Car manufacturers seem to be able to extract a larger profit from these vehicles as compared to regular vehicles and that’s because SUVs are not much more expensive to make from a producers’ perspective - they’re just a bit taller, especially the new crossover models - but consumers perceive them as much more valuable and therefore they are willing to pay a much higher price on the market, and that tends to increase the profit margins for the auto makers which then obviously are keener to sell more and more of those vehicles with high profit margins as compared to other vehicles on which they make smaller margins. Then what happens is that an increasing number of models on the vehicle market - as we’ve seen in this graph for the German market - an increasing number of vehicles become SUVs and at the same time the producers tend to withdraw from the market other vehicles, such as small vehicles, as we see in this graph.

The demand side is often emphasized by common interpretations, for example, by International Energy Agency, or by the media where it’s often argued that it’s a question of consumer taste and preferences - consumers have discovered a love for SUVs.

There certainly seems to be a latent demand for these vehicles and we don’t really know why that is. There are several explanations, more or less plausible regarding for example fashion, regarding the convenience of those larger vehicles, for people who have back problems, older people and so on. But also by the fact that these vehicles are perceived as safer, even though they are not necessarily safer, as they are more likely to roll over. But besides these reasons related to demand and consumer preferences and taste, there are also reasons on the supply side, and these are often neglected.

Car manufacturers seem to be able to extract a larger profit from these vehicles as compared to regular vehicles and that’s because SUVs are not much more expensive to make from a producers’ perspective - they’re just a bit taller, especially the new crossover models - but consumers perceive them as much more valuable and therefore they are willing to pay a much higher price on the market, and that tends to increase the profit margins for the auto makers which then obviously are keener to sell more and more of those vehicles with high profit margins as compared to other vehicles on which they make smaller margins. Then what happens is that an increasing number of models on the vehicle market - as we’ve seen in this graph for the German market - an increasing number of vehicles become SUVs and at the same time the producers tend to withdraw from the market other vehicles, such as small vehicles, as we see in this graph.

The number of SUVs on the German market in 2020 was roughly double the one in 2013 while the number of small vehicles had declined during the same period. When that happens, it becomes more difficult for consumers to buy a non-SUV vehicle since so many of the vehicles on the market are SUVs. So that illustrates, demonstrates that you cannot understand this phenomenon by just looking at the consumer side and demand. You need to look at both consumption and production. This problem has deeper roots than just a change in taste and fashion. So you do need a broader and more systemic perspective to understand why these things happen.

## The political economy of car dependence

This was the motivation behind this review paper that we wrote about the political economy of car dependence. In some ways it was a reaction to much sustainable transport research and discourse on the part of activists which we found was too much focused on consumption at the expense of production, too much focus on win-win – so measures that will tick all boxes, all political goals and preferences - and too apolitical in that it tends to see sustainable transport as a technocratic endeavor. We argue by contrast that the fact that transport systems are car dominated is not just an oversight - something that happened despite our best intensions – but that the current car status quo is supported by powerful interests that have interest to make sure that things continue to be as car dominated as they are or become even more so in the future.

In this study, we identified 5 elements of the political economy of car dependence which you can see in this illustration.

The number of SUVs on the German market in 2020 was roughly double the one in 2013 while the number of small vehicles had declined during the same period. When that happens, it becomes more difficult for consumers to buy a non-SUV vehicle since so many of the vehicles on the market are SUVs. So that illustrates, demonstrates that you cannot understand this phenomenon by just looking at the consumer side and demand. You need to look at both consumption and production. This problem has deeper roots than just a change in taste and fashion. So you do need a broader and more systemic perspective to understand why these things happen.

## The political economy of car dependence

This was the motivation behind this review paper that we wrote about the political economy of car dependence. In some ways it was a reaction to much sustainable transport research and discourse on the part of activists which we found was too much focused on consumption at the expense of production, too much focus on win-win – so measures that will tick all boxes, all political goals and preferences - and too apolitical in that it tends to see sustainable transport as a technocratic endeavor. We argue by contrast that the fact that transport systems are car dominated is not just an oversight - something that happened despite our best intensions – but that the current car status quo is supported by powerful interests that have interest to make sure that things continue to be as car dominated as they are or become even more so in the future.

In this study, we identified 5 elements of the political economy of car dependence which you can see in this illustration.

And we looked at how they relate to each other, trying to cover both the production and consumption side. I will cover these briefly in this presentation starting from the car industry which is key in many respects.

## Understanding the car industry

So if you want to understand how the car industry operates, there are a few key facts about it which we tried to summarize in this graph.

And we looked at how they relate to each other, trying to cover both the production and consumption side. I will cover these briefly in this presentation starting from the car industry which is key in many respects.

## Understanding the car industry

So if you want to understand how the car industry operates, there are a few key facts about it which we tried to summarize in this graph.

The key one is that the industry is characterized by very large economies of scale for reasons that have to do with steel production and all steel-body car productions and that tends to have several important implications, chief among them the fact that there are very high break-even points. A high volume of production is required to recover the capital expense. And when that is the case, that means that the industry needs to keep production levels very high and it cannot go very much below a certain rate of production otherwise it will lose money instead of making money. And that being the case, that means that the industry finds it difficult to cope with reductions in demand. So as soon as they have committed to a new large plant, they cannot then adjust production levels to slightly below what they have planned, because if they do so they will not recover their expenses.

So that makes it very difficult for them during an economic crisis when one of the first expenditures that households tend to cut is new cars. It’s very difficult for the industry to cope with this reduction in demand and so that’s why typically then the State jumps in and bails them out with taxpayers’ money. And another implication of economies of scale is that production tends to be concentrated in a small number of very large multinational firms which are then very powerful, but also concentrated in a small number of production sites where there are very large plants which, along with their suppliers, account for a lot of employment in certain regions for example in Europe.

And that means that when the automotive industry enters a crisis, that’s a very big problem for employment at the local level and that also tends to magnify the bargaining power of the automotive industry when it comes to negotiating bailouts and so on. Economies of scale also tend to explain why something happens which environmentalists tend to hate, but also not to understand, which is why we have very large vehicles - 5-seater vehicles which weigh tons - even though most of us use them for driving alone to work. And that’s a typical criticism on the part of environmentalists: that’s irrational wastefulness, why don’t we have smaller and lighter vehicles?

Well that might make sense if you want to optimize ecological efficiency, but from the industry perspective it very much makes sense to produce a lot of 5-seaters because these are suited to all kinds of uses: you can use them to go on holidays, to go to work, and so on. And you don’t need to have different vehicles for all these different purposes, and different people don’t need to have that many different vehicles. If you want to achieve economies of scale, it does make sense to have a general-purpose vehicle like that as the main one on the market.

The key one is that the industry is characterized by very large economies of scale for reasons that have to do with steel production and all steel-body car productions and that tends to have several important implications, chief among them the fact that there are very high break-even points. A high volume of production is required to recover the capital expense. And when that is the case, that means that the industry needs to keep production levels very high and it cannot go very much below a certain rate of production otherwise it will lose money instead of making money. And that being the case, that means that the industry finds it difficult to cope with reductions in demand. So as soon as they have committed to a new large plant, they cannot then adjust production levels to slightly below what they have planned, because if they do so they will not recover their expenses.

So that makes it very difficult for them during an economic crisis when one of the first expenditures that households tend to cut is new cars. It’s very difficult for the industry to cope with this reduction in demand and so that’s why typically then the State jumps in and bails them out with taxpayers’ money. And another implication of economies of scale is that production tends to be concentrated in a small number of very large multinational firms which are then very powerful, but also concentrated in a small number of production sites where there are very large plants which, along with their suppliers, account for a lot of employment in certain regions for example in Europe.

And that means that when the automotive industry enters a crisis, that’s a very big problem for employment at the local level and that also tends to magnify the bargaining power of the automotive industry when it comes to negotiating bailouts and so on. Economies of scale also tend to explain why something happens which environmentalists tend to hate, but also not to understand, which is why we have very large vehicles - 5-seater vehicles which weigh tons - even though most of us use them for driving alone to work. And that’s a typical criticism on the part of environmentalists: that’s irrational wastefulness, why don’t we have smaller and lighter vehicles?

Well that might make sense if you want to optimize ecological efficiency, but from the industry perspective it very much makes sense to produce a lot of 5-seaters because these are suited to all kinds of uses: you can use them to go on holidays, to go to work, and so on. And you don’t need to have different vehicles for all these different purposes, and different people don’t need to have that many different vehicles. If you want to achieve economies of scale, it does make sense to have a general-purpose vehicle like that as the main one on the market.

One of the key tendencies of the automotive industry is to push through as many vehicles as possible and that’s happened over the course of the twentieth century as we see in this graph, the number of vehicles produced per year has increased very rapidly up to very recently where it has declined mostly because of Covid but also because of saturation of the Chinese market and a shortage of superconductors probably, that’s what some people argue, we don’t really know - but we will see how long this reduction in car production will last. It might bounce back after Covid and certainly the long-term trend is towards increasing numbers of vehicles produced over time.

And as more and more vehicles are produced that creates a pressure on society to accommodate all these vehicles.

## Provision of car infrastructure

And the way in which that has happened brings us to the second point in our list which is car infrastructure and by that we mean roads and parking and all those kinds of things which accommodate vehicles in public space. This is where a lot of public money has gone into accommodating vehicles over the last decades, into expanding the road network and so on. Things like road building tend to be justified by policy makers in a variety of different ways which we’ve tried to summarize in this figure.

One of the key tendencies of the automotive industry is to push through as many vehicles as possible and that’s happened over the course of the twentieth century as we see in this graph, the number of vehicles produced per year has increased very rapidly up to very recently where it has declined mostly because of Covid but also because of saturation of the Chinese market and a shortage of superconductors probably, that’s what some people argue, we don’t really know - but we will see how long this reduction in car production will last. It might bounce back after Covid and certainly the long-term trend is towards increasing numbers of vehicles produced over time.

And as more and more vehicles are produced that creates a pressure on society to accommodate all these vehicles.

## Provision of car infrastructure

And the way in which that has happened brings us to the second point in our list which is car infrastructure and by that we mean roads and parking and all those kinds of things which accommodate vehicles in public space. This is where a lot of public money has gone into accommodating vehicles over the last decades, into expanding the road network and so on. Things like road building tend to be justified by policy makers in a variety of different ways which we’ve tried to summarize in this figure.

As we’ve seen here, there are very many different justifications there, partly contradictory, as for example when road building is justified as necessary to accommodate economic growth which results in increased traffic and congestion, whereby it is argued that we need to predict and provide in advance for these increases in traffic.

But it’s also sometimes argued that road building is necessary to stimulate economic growth, so basically, whether your economy is growing or not growing, you sort of always need road building from this perspective. And there are other ways less politically charged, less economically focused to justify road building, such as: it’s a way to accommodate consumer preferences; there are more left-wing ways to justify road building in terms of making sure that certain rural regions in particular can catch up with the rest of the country in economic terms; there are more technocratic ways of justifying that, as in for example because cost-benefit analysis has sanctioned that to be in the common interest; and so on. There are many different ways to justify road building and they tend to cover pretty much all of the political spectrum and other aspects as well, which makes any discourse that goes against road building marginalized. It almost doesn’t have any citizenship in the political debate.

## Car dependent land use patterns

A third factor related to car dependencies are car dependent land use patterns, often referred to as urban sprawl. That tends to be seen in the debate as something that has happened despite our best intentions, a form of planning oversight, an irrational and wasteful form of urban development that we should have known better than to implement. I suppose there’s some truth to that argument, but we argue in this paper that it’s not entirely an accidental outcome, that these land use patterns tend to prevail, because even though they are wasteful, they tend to maximize demand for certain goods, for certain industries such as the housing industry, which builds all those small houses in the periurban areas. Demand for road building, demand for oil, demand for cars and so on. So what we argue is that urban sprawl can also be seen as a form of stimulus, that the State encourages in order to create demand for a certain key industry, and it’s certainly been a form of stimulus at some point in History, in some countries.

## Provision of public transport

The next element that you need to consider in the political economy of car dependence, is public transport. It is often argued that public transport is impossible to provide in a convenient way when land use patterns are too car-oriented.

I suppose that’s true to some extent but it’s also not true in that you can provide decent public transport even in low density areas, but you do need to follow a certain approach which is called network planning, which requires public transport to be very much integrated and that you can only do if there is a rather strong public control on at least the planning of public transport. And that means that it’s not possible to provide competitive public transport in countries where public transport has been very much deregulated and privatized, such as for example in the UK, and that’s also a political economy factor that we need to take into account.

## The culture of car consumption

And last but not least in our list of elements of the political economy of car dependence comes the cultures of car consumption. We argue that of course consumers are attached to cars after decades of car dependence in many ways, they tend to perceive them as symbols of freedom, of social status, of masculinity sometimes, of independence for women. Also more recently as cocoons that protect you from a hostile urban environment. But mostly they tend to be seen nowadays as the normal thing to do, as something taken for granted. All of us who try to live without a car know that you sort of need to justify that choice with your peers, whereas you don’t need to justify the choice to buy one most of the time. So it tends to be very much entrenched in our culture nowadays. And this cultural aspect is important in explaining the SUV boom as consumers tend to perceive them as very aggressive cars, or powerful, cars that tell something about your social status and allow you to prevail in a competition with other drivers on the road.

## Four cross cutting characteristics of political car dependence

So to conclude, our analysis of the different elements of the political economy of car dependence leads us to identify 4 underlying and cross cutting characteristics of car-dependent transport system that sort of cut across these different elements. The first one being the role of social technical systems of provision which sounds very academic jargon but what it means basically is that you need to look at both social aspects and technical aspects, and both consumption and production, and that’s something that no discipline can do on its own, you do require a sort of interdisciplinary approach, a more systemic approach to capture the complexity of such a thing.

The second characteristic is what we call the opportunistic use of contradictory economic arguments, which we’ve seen for example in road building whereby both economic growth and economic decline are reasons to build roads. But you also see that with the car industry, which is simultaneously presented as a free-market champion but also in need of public bailouts every couple of years when demand goes down. And the third characteristic is perhaps the most important, it is the creation of an apolitical façade around car dependence and car decision-making and the current pro-car status quo, in that it is normalized, it is seen as taken for granted, and even though lots of public resources go into supporting it through hidden subsidies, that is seen as normal and almost not as a subsidy at all, whereas subsidies that go into competitors such as public transport tend to be questioned in terms of waste of public money and so on.

There are other manifestations of that such as when the domination that the car has over public space is seen as a normal thing to do and taking away a little bit of that space and giving it to other modes is seen as something radical, even though there is no reason when you think about it why so much space should go into providing space for a certain section of the population which owns and uses cars to the detriment of others who don’t. So this sort of apolitical façade creates a situation where it’s just seen as common sense to support this status quo and if you question it, you’re marginalized and portrayed as someone lacking common sense, as a hippie or as an authoritarian who wants to take away things from the population that are taken for granted.

The fourth and final characteristic is what we call the capture of the State by the car dependent transport system and here we refer to the fact that pro-car decision making is very much entrenched and very hard to dislodge and there are many reasons for that. One is lobbying of course, there are some powerful interests that lobby upon the State to do so. But it goes deeper than that in that there is something called State dependence, whereby the State is dependent on the automotive industry for income revenue, for employment and so on. So it doesn’t see its interests as different from those of the industry, and you see that particularly strongly in certain countries which have a particularly large and powerful automotive industry.

## Going beyond car dependence

So to conclude on a slightly more positive note, if I can, what lessons can we draw from this analysis in terms of how to go beyond car dependence and car dependent transport system? Two steps are necessary there in our opinion. The first one is a more cognitive one, it’s to see sustainable transport as more of a political endeavor, not as something technocratic that will appeal to all sides and all interests, but as something that is actively opposed by certain powerful interests that need to be named and identified otherwise there will be little chance to go beyond it.

Second, we would argue that since all these elements exist very much interconnected with one another, then a successful strategy to go beyond a car dependent transport system will need to tackle all of these elements at once. Because if you focus on just one or two of them, there are powerful synergies between them that tend to support the status quo. So one needs to have a bit more of a systemic and global vision of this problem than has perhaps been the case to date.

As we’ve seen here, there are very many different justifications there, partly contradictory, as for example when road building is justified as necessary to accommodate economic growth which results in increased traffic and congestion, whereby it is argued that we need to predict and provide in advance for these increases in traffic.

But it’s also sometimes argued that road building is necessary to stimulate economic growth, so basically, whether your economy is growing or not growing, you sort of always need road building from this perspective. And there are other ways less politically charged, less economically focused to justify road building, such as: it’s a way to accommodate consumer preferences; there are more left-wing ways to justify road building in terms of making sure that certain rural regions in particular can catch up with the rest of the country in economic terms; there are more technocratic ways of justifying that, as in for example because cost-benefit analysis has sanctioned that to be in the common interest; and so on. There are many different ways to justify road building and they tend to cover pretty much all of the political spectrum and other aspects as well, which makes any discourse that goes against road building marginalized. It almost doesn’t have any citizenship in the political debate.

## Car dependent land use patterns

A third factor related to car dependencies are car dependent land use patterns, often referred to as urban sprawl. That tends to be seen in the debate as something that has happened despite our best intentions, a form of planning oversight, an irrational and wasteful form of urban development that we should have known better than to implement. I suppose there’s some truth to that argument, but we argue in this paper that it’s not entirely an accidental outcome, that these land use patterns tend to prevail, because even though they are wasteful, they tend to maximize demand for certain goods, for certain industries such as the housing industry, which builds all those small houses in the periurban areas. Demand for road building, demand for oil, demand for cars and so on. So what we argue is that urban sprawl can also be seen as a form of stimulus, that the State encourages in order to create demand for a certain key industry, and it’s certainly been a form of stimulus at some point in History, in some countries.

## Provision of public transport

The next element that you need to consider in the political economy of car dependence, is public transport. It is often argued that public transport is impossible to provide in a convenient way when land use patterns are too car-oriented.

I suppose that’s true to some extent but it’s also not true in that you can provide decent public transport even in low density areas, but you do need to follow a certain approach which is called network planning, which requires public transport to be very much integrated and that you can only do if there is a rather strong public control on at least the planning of public transport. And that means that it’s not possible to provide competitive public transport in countries where public transport has been very much deregulated and privatized, such as for example in the UK, and that’s also a political economy factor that we need to take into account.

## The culture of car consumption

And last but not least in our list of elements of the political economy of car dependence comes the cultures of car consumption. We argue that of course consumers are attached to cars after decades of car dependence in many ways, they tend to perceive them as symbols of freedom, of social status, of masculinity sometimes, of independence for women. Also more recently as cocoons that protect you from a hostile urban environment. But mostly they tend to be seen nowadays as the normal thing to do, as something taken for granted. All of us who try to live without a car know that you sort of need to justify that choice with your peers, whereas you don’t need to justify the choice to buy one most of the time. So it tends to be very much entrenched in our culture nowadays. And this cultural aspect is important in explaining the SUV boom as consumers tend to perceive them as very aggressive cars, or powerful, cars that tell something about your social status and allow you to prevail in a competition with other drivers on the road.

## Four cross cutting characteristics of political car dependence

So to conclude, our analysis of the different elements of the political economy of car dependence leads us to identify 4 underlying and cross cutting characteristics of car-dependent transport system that sort of cut across these different elements. The first one being the role of social technical systems of provision which sounds very academic jargon but what it means basically is that you need to look at both social aspects and technical aspects, and both consumption and production, and that’s something that no discipline can do on its own, you do require a sort of interdisciplinary approach, a more systemic approach to capture the complexity of such a thing.

The second characteristic is what we call the opportunistic use of contradictory economic arguments, which we’ve seen for example in road building whereby both economic growth and economic decline are reasons to build roads. But you also see that with the car industry, which is simultaneously presented as a free-market champion but also in need of public bailouts every couple of years when demand goes down. And the third characteristic is perhaps the most important, it is the creation of an apolitical façade around car dependence and car decision-making and the current pro-car status quo, in that it is normalized, it is seen as taken for granted, and even though lots of public resources go into supporting it through hidden subsidies, that is seen as normal and almost not as a subsidy at all, whereas subsidies that go into competitors such as public transport tend to be questioned in terms of waste of public money and so on.

There are other manifestations of that such as when the domination that the car has over public space is seen as a normal thing to do and taking away a little bit of that space and giving it to other modes is seen as something radical, even though there is no reason when you think about it why so much space should go into providing space for a certain section of the population which owns and uses cars to the detriment of others who don’t. So this sort of apolitical façade creates a situation where it’s just seen as common sense to support this status quo and if you question it, you’re marginalized and portrayed as someone lacking common sense, as a hippie or as an authoritarian who wants to take away things from the population that are taken for granted.

The fourth and final characteristic is what we call the capture of the State by the car dependent transport system and here we refer to the fact that pro-car decision making is very much entrenched and very hard to dislodge and there are many reasons for that. One is lobbying of course, there are some powerful interests that lobby upon the State to do so. But it goes deeper than that in that there is something called State dependence, whereby the State is dependent on the automotive industry for income revenue, for employment and so on. So it doesn’t see its interests as different from those of the industry, and you see that particularly strongly in certain countries which have a particularly large and powerful automotive industry.

## Going beyond car dependence

So to conclude on a slightly more positive note, if I can, what lessons can we draw from this analysis in terms of how to go beyond car dependence and car dependent transport system? Two steps are necessary there in our opinion. The first one is a more cognitive one, it’s to see sustainable transport as more of a political endeavor, not as something technocratic that will appeal to all sides and all interests, but as something that is actively opposed by certain powerful interests that need to be named and identified otherwise there will be little chance to go beyond it.

Second, we would argue that since all these elements exist very much interconnected with one another, then a successful strategy to go beyond a car dependent transport system will need to tackle all of these elements at once. Because if you focus on just one or two of them, there are powerful synergies between them that tend to support the status quo. So one needs to have a bit more of a systemic and global vision of this problem than has perhaps been the case to date.

Activer

Désactivé

Ajouter le trianglesi ce contenu est affiché dans la quinzaine

Désactivé

Chapô

The reduction of greenhouse gas emissions generated by the car is at the heart of ecological transition strategies. In order to understand its dominant role and envisage its future, supporters and detractors alike question the demand for cars: citizens have an insatiable desire for them, with a preference for large and powerful vehicles that appear safe to drivers. However, the supply side, i.e. the car industry and the political economy that supports it, has long been overlooked in research. Giulio Mattioli proposes to take a closer look at it in order to revisit our dependence on the car.

Envoyer une notification

Désactivé

Thématique