21 november 2022

The city of Seville is unique for its success in promoting cycling as an integral part of its urban mobility in only five years (2006-2011), through the implementation of a well-designed, safe and comfortable network of cycle paths covering all the city. This achievement, however, has not been followed by a substantial improvement of cycling mobility in the years since. This article analyses the political, social and infrastructural causes behind this success and the following stagnation, including the role of the COVID-19 pandemic in this evolution. The author feels that both positive and negative lessons may be extracted from this analysis, which may be useful for other similar cities.

From 2011, the city of Seville became a global reference for promoting successful cycling policies. Seville was not unique, however, either for the figures reached by the bicycle in the city’s modal share, or for any special features of its cycling infrastructure. In this regard, practically any Dutch, Danish or German city would surpass Seville in its achievement. What made Seville different was the short period of time (no more than four years) in which the city went from being a place where the bicycle was barely used, to one in which cycling is present as a mode of transport in the everyday life of its citizens.

This exceptional period, where bicycle use rose from almost nothing to 6% in the modal share of the city, was followed by a period of stagnation and decline, where bicycle use remained approximately constant with oscillations, including during the Covid-19 pandemic, when cycling promotion policies were largely absent.

This article reports on the main relevant facts during the boom in bicycle use during the period 2007-2011 and the causes of the subsequent stagnation and decline, as well as the main current challenges for cycling promotion policies in the city.

Seville is a city with a compact urban design in its central area (the municipality of Seville), surrounded by an extensive metropolitan ring formed by a multitude of small and medium-sized municipalities. The population of the municipality of Seville has remained practically constant from 1990 to the present, at around 700,000 inhabitants. In sharp contrast, the population of the metropolitan ring has been growing continuously since 1990 to the present, reaching figures similar to those of the central area. But its population density is considerably lower than in the central area (more than 10 times less) which has hindered the creation of an effective, integrated public transport network. Moreover, the outer ring is largely made up of commuter towns that are economically dependent on the central area, which together with poor public transport, generates high car dependence and significant congestion problems on access roads. This article refers mainly to the central area, but we will return briefly to the outer ring and to the possible role of the bicycle in this area in the final section.

Since the 1990s, Seville has had a strong pro-cycling movement, represented by the association A Contramano. As an example, Fig.1 shows the cover photo of a local newspaper, El Correo de Andalucía, from 31 May 1993, of a cyclists’ demonstration organized by A Contramano the previous day with the slogan “Cycle Paths Now!” More than 10,000 people participated in this protest.

Fig.1 Cover page of the “El Correo de Andalucía” 05/31/1993

In 2004, the main social democratic party of the country, the Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) won the municipal elections and formed a coalition with Communist and Green parties to govern the city. The latter members of the governing coalition were strongly influenced by the pro-cycling social movement and asked for the implementation of a network of bike paths. People such as deputy mayor Paula Garvin and José Antonio García-Cebrian 1 , as well as the mayor, the socialist Alfredo Sánchez-Monteseirin, played an important role in the negotiations and the subsequent decision to build an extensive network of cycle paths in only four years. The strong political will of these politicians, and their close collaboration with the pro-cycling social movement, nurtured the success of the initiative. The political decision to create the entire cycle network in just four years was instrumental in its success, because it immediately made the entire city accessible to citizens likely to cycle. As a consequence, many citizens chose to cycle, as we show below. Ultimately, this was a socially successful initiative which led to a political achievement for the political leaders who drove it.

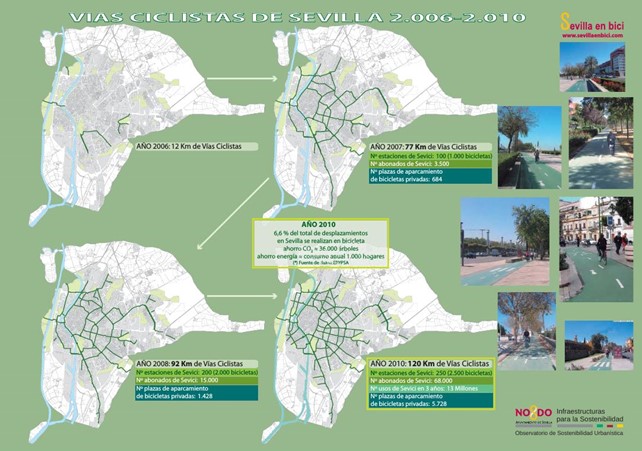

Fig.2: Evolution of Seville's network of cycle-paths (2006-2010). Source: Municipality of Seville

This network was planned and built from 2006 to 2010 (Fig.2), with a budget of €32 million. By 2010 the network was 120 km long and covered all the populated areas of the municipality with a bidirectional, continuous, homogeneous and comfortable cycling infrastructure. Strong restrictions were imposed on non-residents’ car traffic in the city center, where the very old and narrow streets prevented the creation of bike paths. Instead, traffic calming policies were implemented including the creation of new pedestrian areas. A public bicycle-sharing system with 2,500 bicycles and 250 stations covering the whole city was also implemented in 2007, which soon served thousands of participants.

Fig.3: A typical cycle path in Seville at peak hour. Author’s photograph

Fig.3 shows a picture of a cycle path in the city. Thousands of cyclists per day pass through the most crowded points of the network. It also illustrates the typical design of Seville's cycle paths. They were mostly built at the same level as the pavement, in order to enhance the feeling of safety for potential cyclists, but they were situated on former car parking lanes, in order to not reduce the space available for pedestrians. The remaining line of trees, located where the pavement previously ended, helps to define the spaces for pedestrians and cyclists in an unobtrusive way.

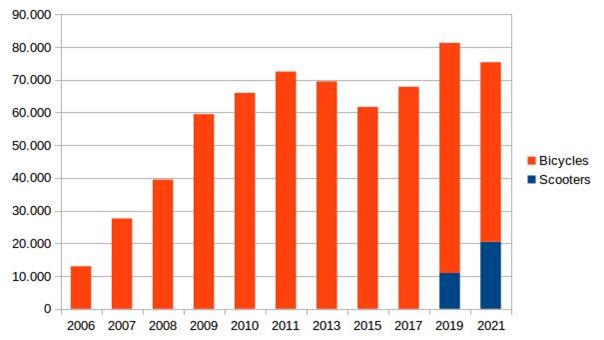

Because of this policy, cycling grew sharply in the city, reaching an estimated modal share of around 6% of total trips 2 . Fig.4 shows the estimates of the total number of trips in the network of cycle paths on a typical working day from 2006 to 2021. It is interesting to note that the peak of cycling trips in 2011 coincided with the establishment of robust restrictions on traffic in the city center

Fig.4: Evolution of the number of trips on the network of cycle paths on a typical sunny working day. These estimates are based on systematic counts at specific points along the network, where the percentage of trips on public bikes is measured. Since the total number of public bike rentals in the city is known, the total number of trips can be easily estimated from this data. Source: Municipality of Seville and author's own elaboration. Special thanks to Manuel Calvo for providing the data for this graph.

The sharp increase of urban cycling in the period 2006 – 2011 can be clearly seen in Fig.4. This period was followed by a stagnation with oscillations and a decline in the subsequent years. The peak of cycle trips recorded in 2011 was followed by a reduction of around 10,000 trips from 2011 to 2015 (from 72,000 to just 62,000). It then increased once again in the next four years to levels similar to 2011 (70,000 trips counting only bicycles and not scooters). It then declined again to 55,000 bicycle trips in 2021. The cycling boom correlated with the creation of the network of cycle paths, and the subsequent period of decline reflects the presence in the city of a more pro-car mayor, from the main conservative party of the country -the People’s Party (PP) - who ended the pro-cycling policies of his predecessor: Cycling promotion initiatives were curtailed, and specific measures such as restrictions on car traffic in the city center were reversed, although not without opposition from many pro-cycling social movements. In fact, the People’s Party’s electoral victory was mainly fueled by national policy priorities (such as the economic crisis) and did not reflect any significant popular opposition to the previous pro-cycling policy. This is evidenced in part by the resilience of cycling mobility choices, which experienced only a moderate decline.

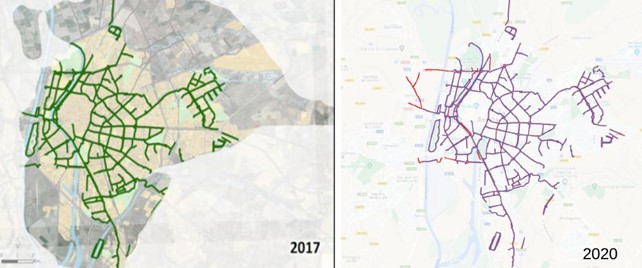

The fact that this decline was contemporary of a further growing of the cycle network (see Fig.6, left) may seem surprising, but it should be taken into account that such growth was mainly on peripheral areas and, most important, that whereas the implementation of basic cycle network ensuring safety for cyclists is a basic pre-condition of any successful policy aimed to promote urban cycling, once this condition has been fulfilled other measures, such as a traffic regulation favoring cyclists (and restricting car traffic), soft educational and promotional programs, political messages supporting cycling as an activity beneficial for the city, and so on, become more and more important. All these policies and messages were absent from the city government during the period 2011- 2015

In 2015 the main Spanish social democratic party (PSOE) won the local elections and rates of cycling rose once again. Since 2015 there has been a single-party PSOE led-government in Seville, which has been responsible for policies during the pandemic and after. One of the most salient features of recent years, see Fig.4, is the growing presence in the cycle paths of electric scooters, which are permitted to travel on them. I will return to this point later.

The special measures to tackle COVID-19 were imposed in Spain from March 2020 to June 2021, the hardest period lasting from the middle of March to the end of April 2020. During this period the population was confined at home, except for essential activities. By the end of April, the population was allowed to return to outdoor spaces, at first for physical exercise only and then, gradually, for other non-essential activities. This resulted in an explosion of cycling and walking in the city, as illustrated in Fig.5, which shows a traffic light on one of the most central avenues of the city, crowded with cyclists and pedestrians, but devoid of cars.

Fig.5: A traffic light in a main avenue of Seville crowded with cyclists and pedestrians but devoid of cars during the pandemic. Author’s photograph.

Many cities around the world took advantage of this situation to promote active mobility, opening new pop-up bicycle lanes and expanding pedestrian or traffic calming areas. These policies were absent in Seville where no pop-up bicycle lanes or new pedestrian areas were created. Of course, the core network of bicycle paths continued to expand, albeit at a slower rate, following previously agreed plans, but almost all new cycle paths were in peripheral areas and did not contribute to any substantial improvement of the overall city network. Fig.6 shows the growth of this network in the period 2017-2020.

Fig.6: Expansion of the network of cycle paths from 2017 to the end of 2020. New cycle paths are in red. In total the network grew 8 km in this period, from 187 km in 2017 to 195 km in 2020. Source: Municipality of Seville and author's own elaboration.

To further illustrate the myopic attitude of the municipality: while many cities in Europe promoted their public bicycle-sharing schemes, offering their citizens a healthy alternative form of transport to cars during the lockdown, in Seville (as in most Spanish cities) these schemes were closed. Bicycle handlebars were blamed for spreading infection in the population, but grab rails on buses were not!

Seville was not the only Spanish city that had developed effective pro-cycling policies in this period. Before Seville, San Sebastian (Donosti), in the Basque Country, and Barcelona had successfully implemented networks of bicycle paths. Simultaneously or shortly after Seville, Vitoria, Valencia, Zaragoza and Cádiz also implemented such networks following a similar design. In most of these cities the local government was formed by left-wing parties (including the PSOE or others), with the notable exception of Vitoria, were the conservatives led the transformation. In Barcelona and Valencia, pop-up bicycle lanes were created during the pandemic. In many of these cities public bicycle-sharing schemes were also implemented. In all cases such policies had a meaningful impact on city mobility, with substantial increases in urban cycling. In all cases too, pro-bicycle associations, federated in a national network, participated in these initiatives.

Seville, therefore, was not an isolated case. Currently, those Spanish cities interested in developing pro-cycling policies participate in a network, the Red de Ciudades por la Bicicleta, and the Spanish Government, led by a coalition between the PSOE and Unidas Podemos, has developed a National Cycling Strategy (2021) with the aim of improving cycling as a part of urban mobility. This strategy includes the creation of cycling infrastructure (cycle paths, bicycle parking and bicycle-sharing systems) as well as campaigns (cycle to work) along with specific objectives in areas including health promotion and cycle tourism. However, it should be emphasized that it is only a transversal strategy, without its own dedicated budget.

The absence of cycling promotion policies during and after the pandemic helps to explain why, as the data in Fig.4 for 2021 clearly shows, urban cycling in Seville has declined. Besides this fact, more profound causes can be discussed. Indeed, in the case of Seville it confirms that, while the implementation of a safe and comfortable network of bicycle paths is an essential component of any successful policy to promote urban cycling, further complementary strategies are necessary to fully integrate cycling in the city’s transport plan, as a part of a coherent policy towards sustainable mobility.

Firstly, effective car traffic restriction policies, as well as policies to create proximity by relocating activities, are essential for effectively promoting walking and cycling because the “mobility market” is a closed one, that is, the trips made each day by a given person are usually constant and relate to daily trips such as work, study and shopping. What occurs, therefore, is a transfer of trips, in this case from the car to the bicycle. In this respect it might be significant that the peak of cycling activity in Seville took place while traffic restrictions were imposed in the historical center of the city in 2011. In subsequent years, these restrictions were removed by the new pro-car mayor, and nowadays no effective car traffic restrictions are in place in the city center, despite the experience of the pandemic in showing pathways to implement them, and despite a new, more pro-cycling mayor is in the City Hall

Furthermore, no policies for safe bicycle parking have been implemented at the main origin (households) and destination points (workplaces, schools, shopping malls and public transport hubs). Although thousands of bicycle parking spaces were created in streets at the same time as the implementation of the network of cycle paths, and in recent years the municipality enacted policies to promote safe bicycle parking at households and at public transport hubs, this was not enough to encourage all citizens to cycle, because of their fear of bicycle theft, which strongly affects the disposition to cycle 3 . The most notable exception was the University of Seville which, prior to the implementation of the bicycle network, developed its own successful programme of closed bicycle parking lots (see Fig.7) for students, professors and administrative staff, which had a notably positive impact on cycling amongst this community, showing the effectiveness of these kinds of policies for promoting cycling.

Fig.7 A closed bicycle parking lot at Seville's University. Author’s photograph.

In addition, and as was already mentioned, the implementation of a complete network of cycle paths was restricted to the municipality of Seville. The metropolitan ring, with a population like that of the main municipality, has only a few bicycle paths, and these are not connected. Furthermore, there are not enough cycling bridges on the main ring roads, which in practice act as barriers to cycling. Such scant infrastructure prevents the formation of a real cycle network and needs to be improved, making it continuous and comfortable, since the usefulness of a network of cycle paths depends crucially on these two characteristics: continuity and comfort. Presently, such infrastructure is being improved, thanks to the efforts of many local authorities, partially taking advantage of EU Next Generation funding, but the lack of a unified plan is restricting its impact.

Also crucial for the integration of cycling in metropolitan mobility is its integration in the metropolitan urban transport system. Synergies between cycling and urban transport are well known, mainly for widening the catchment areas of public transport stations. In Seville these synergies are poorly developed. Bike on board schemes are only implemented in urban and suburban trains and not during rush hour periods. Bike and ride alternatives are also poorly developed, except for some insufficient cycle parking inside some suburban train stations. In the city of Seville, the municipality has implemented a big, closed parking lot at the main metropolitan train transport hub, but the usefulness of this initiative is limited by the absence of its counterparts in the metropolitan ring. More successful is the current bicycle-sharing system installed at the city’s main metropolitan bus station following the model of the Dutch O.V. fiets. But in any case, they are isolated initiatives which do not constitute a genuine system of intermodality between bicycles and public transport.

Finally, there is presently a significant and growing tendency to choose electric scooters over bicycles, as evidenced by the data for 2019 and 2021 (Fig.4). According to a national regulation, electric scooters without seats can be used on bicycle paths. These are very convenient vehicles that are more portable than bicycles. This fact might explain their success in a scenario where cyclists experience difficulties parking at home and at destinations or in combining them with public transportation. But, of course, electric scooters are motorised vehicles that do not provide the same health benefits and sustainability of bicycles. Seville's municipality has limited the use of cycle paths to scooters under 250 W (the same as for electric bicycles), but the opinion of this author is that the proliferation of motorised traffic on cycle paths requires a deeper discussion.

In summary, the experience of Seville is a good example of how the implementation of a safe and comfortable network of cycle paths results in a significant growth of urban cycling, but also shows that this is not sufficient for developing the full potential of cycling for active and sustainable mobility. Complementary policies, such as car traffic restrictions and the provision of safe bicycle parking at households, workplaces, schools, malls and public transport hubs are also necessary to maintain and go beyond the initial momentum provided by the cycle path network and integrate bicycle promotion initiatives into a global policy towards sustainability. Otherwise, stagnation or even a decline in cycling due to the presence of other less sustainable and healthy alternatives of transport may occur.

The rapid implementation of a cycle network covering the whole city was crucial for success. This was a fundamental characteristic of the process, and probably the most important one. In only four years many Sevillians realized that they could easily cycle between any two points in the city. It confirms that having an complete network is crucial and therefore the importance of implementing it in the shortest period of time.

On the negative side no coherent mobility policies focusing on transport sustainability have been enacted in Seville since 2011, including measures such as car traffic restriction and traffic calming. The absence of such policies, building on the success of the cycling promotion policies from 2007 to 2011, may undermine the transition to sustainable urban mobility. It shows, once again, the importance of a holistic vision of mobility.

• Marqués, R., Hernández-Herrador, V., Calvo-Salazar, M., & García-Cebrián, J. A. (2015). How infrastructure can promote cycling in cities: Lessons from Seville. Research in Transportation Economics, 53, 31-44.

• Geller, R., & Marqués, R. (2021). 19 Implementation of Pro-bike Policies in Portland and Seville. In Buehler, R., & Pucher, J. (Eds.). (2021). Cycling for sustainable cities 74. MIT Press.

Acknowledgement: The author is in debt with Manuel Calvo, Vicente Hernández and Emilio Minguito for kindly providing many data for this article, and for hours of useful and pleasant conversation.

1 Both members of “A Contramano”.

2 Marqués, R., Hernández-Herrador, V., Calvo-Salazar, M., & García-Cebrián, J. A. (2015). How infrastructure can promote cycling in cities: Lessons from Seville. Research in Transportation Economics, 53, 31-44.

3 In Seville and other Spanish cities you can hardlyrarely see bicycles paked parked at night on the streets for by the same reason.

Movement is the crossing of space by people, objects, capital, ideas and other information. It is either oriented, and therefore occurs between an origin and one or more destinations, or it is more akin to the idea of simply wandering, with no real origin or destination.

En savoir plus xFor the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xActive mobility refers to all forms of travel that require human energy (i.e. non-motor) and the physical effort of the person moving. Active mobility occurs via modes themselves referred to as “active,” namely walking and cycling.

En savoir plus xThe lockdown measures implemented throughout 2020 in the context of the Covid-19 crisis, while varying from one country to the next, implied a major restriction on people’s freedom of movement for a given period. Presented as a solution to the spread of the virus, the lockdown impacted local, interregional and international travel. By transforming the spatial and temporal dimensions of people’s lifestyles, the lockdown accelerated a whole series of pre-existing trends, such as the rise of teleworking and teleshopping and the increase in walking and cycling, while also interrupting of long-distance mobility. The ambivalent experiences of the lockdown pave the way for a possible transformation of lifestyles in the future.

En savoir plus xTheories

Other publications