20 February 2024

In recent years, Algeria has seen ongoing debates surrounding vehicle imports, their manufacture, motorisation, the infrastructures supporting them, and the persistent issue of congestion, notably in the capital. There is a constant tension between the aspiration to cater to market demands and the imperative to cultivate local industries so as to reduce a national dependency on imports. This dynamic unfolds within a context where it is a struggle to develop alternatives to automobiles.

In recent years, Algeria has seen ongoing debates surrounding vehicle imports, their manufacture, motorisation, the infrastructures supporting them, and the persistent issue of congestion, notably in the capital. There is a constant tension between the aspiration to cater to market demands and the imperative to cultivate local industries so as to reduce a national dependency on imports. This dynamic unfolds within a context where it is a struggle to develop alternatives to automobiles.

The automobile unquestionably holds a significant position in the collective imagination, symbolising not only emancipation, social success, and modernity but also representing, for many individuals, the only viable solution to the need for mobility in a setting that offers few alternatives. Improving traffic flow and access to mobility constitute pressing concerns for Algerian society, which is currently undergoing a transitional period towards heightened motorised mobility. This shift is further driven by changing purchasing power, advancements in infrastructure, and the socio-spatial reconfiguration of cities and territories (Safar-Zitoun, 2020). 1

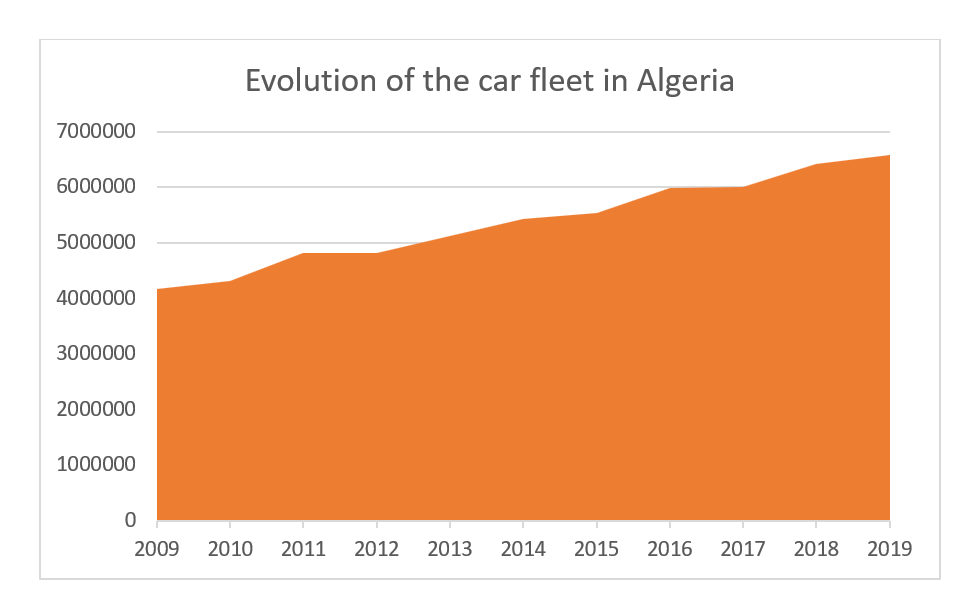

According to the National Statistics Office, at the end of 2019, Algeria had 6.5 million vehicles for a population of approximately 46 million inhabitants 2, an increase of roughly 2.5 million vehicles over a decade. Youssef Nebache, the former president of the multi-brand car dealers' association, quoted in the national press, asserts that the country still requires a million new cars to rejuvenate its aging vehicle fleet. 3 However, from 2017 to 2023, vehicle imports were stopped, and the assembly industry came to a standstill. Although investment in infrastructure, including roads and freeways, persists, alternatives to the automobile, particularly public transport, struggle to develop.

Figure 1: Evolution of the car fleet in Algeria between 2009 and 2019 (created by the author, source: www.ons.dz)

The automotive system finds itself at an impasse, caught between the imperative to address the escalating demand for vehicles and the economic and political pressures to curtail its expansion. This paradoxical scenario arises from a political will to diminish reliance on imports and reduce expenditure, especially as hydrocarbon prices began to decline in 2015. The subsequent measures implemented have directly impacted the automotive system and mobility at large. This creates tension between the imperative for ecological and mobility transitions and the population’s growing need for mobility, alongside national policies geared towards economic and industrial development. Mobility appears to vacillate between an exclusive focus on automobiles and faint hints of a sustainable transition struggling to materialise.

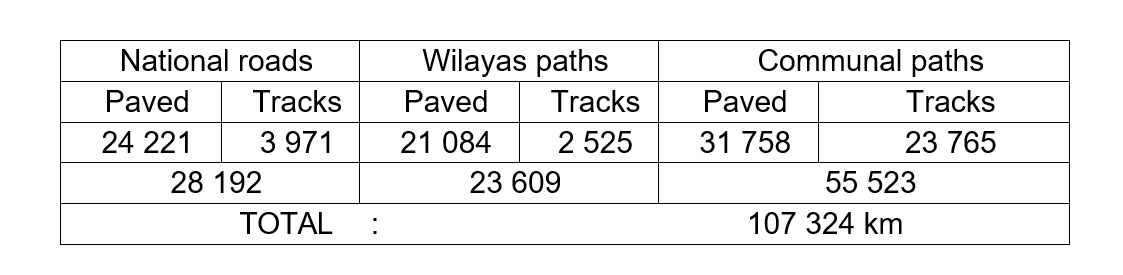

As the backbone of the automotive system, road infrastructure is a major concern in Algeria. The idea that infrastructure drives development 4 (Ravalet, 2014) has underpinned numerous pivotal decisions since the country gained independence in 1962. Focused on improving the control of its territory as Africa's largest nation (2,382 million km2), Algeria's strategic focus has been on augmenting its road network, expanding it from 80,000 km to 107,324 km by 2004 (Amcha, 2023).

Table 1: The road network in 2004 5, Source: Les travaux publics en Algérie, Histoire et perspectives [Public Works in Algeria: History and Perspectives], Amcha, 2023.

Since 2005, several significant national and continental infrastructure initiatives have been launched, with the objective of steering territorial and economic development. Foremost among these is the East-West freeway (AEO), marking the largest undertaking in Algeria's history. Envisaged as an integral component of the national regional development plan, it spans approximately 1,216 kilometres and is conceived as part of the broader Maghreb unity highway corridor, projected to extend over 6,800 kilometres, ultimately connecting Nouakchott (Mauritania) to Tripoli (Libya) via Tunisia and Algeria (Amcha, 2023; COJAAL 2008). The final segment is projected to be completed by the end of 2023, and an additional east-west freeway, situated 200 km from the initial route, is planned in the High Plateaus. 6 This freeway aims to link smaller towns nestled behind the Atlas Mountain ranges, which currently remain isolated and less accessible.

Figure 2: Motorway network in May 2015, with the planned route of the East-West freeway between Tébassa and El Aricha (Source: Wikipedia).The second major initiative is the Trans-Saharan African Unity Road, crossing six countries: Algeria, Tunisia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, and Chad. Regarded by public authorities as a pivotal catalyst for economic and social development, regional accessibility, stability, and peace, it has been earmarked as a priority project within the NEPAD program. 7 With a history spanning over 45 years, construction commenced in the early 1970s. This road integrates with the East-West highway, covering a total distance of 4,800 km, with 2,400 km traversing Algerian terrain. Now almost completed, it connects Algiers to the Niger border, supplemented by sections linking Tit/Timaouine (Malian border) over 480 km and Ghardaïa/Tunisia over 512 km (Amcha, 2023). 8 In recent years, Algeria has prioritised it, not only for mobility and transportation but also recognising its significance as an economic and geostrategic imperative.

Figure 3: The Trans-Saharan African Unity Road corridor. Source : JeuneAfrique, 2020.Relying on roads and, consequently, automobiles for its urban and territorial development, Algeria has become wholly dependent on car imports. Due to exchange problems with the Algerian dinar, the financial burden is shouldered by the State, tapping into foreign exchange reserves primarily generated through hydrocarbon exports. While this arrangement served Algeria well in the initial decades of the new millennium, elevated oil and gas prices are anticipated to present greater challenges in the coming decades. This will likely drive the authorities to implement reforms geared towards curbing the import bill in general, with a specific focus on vehicles.

The peak was reached in 2012, with imports exceeding 605,000 units. In the same year, a reform led to a partnership with Renault to establish the first vehicle assembly plant in Algeria, followed by partnerships with Hyundai and Volkswagen in 2014. Citizens and public institutions were urged to refrain from purchasing imported vehicles, and instead support local assembly plants, which inadvertently developed a form of industrial monopoly, further reinforced by the ban on vehicle imports in 2016.

Three years after the establishment of the first plant, in 2017, results were dire: car assembly had negligible impact on foreign exchange reserves, largely attributed to the simultaneous decline in oil prices. Furthermore, the industry failed to generate the expected employment opportunities and incurred higher costs for the State due to subsidies and tax breaks. Moreover, the integration rate 9 fell significantly below the mandated 15% for manufacturers, and, even worse, locally-produced cars proved more expensive than their imported counterparts.

The local press and public authorities concluded that this short-lived foray into the automotive industry was essentially a disguised form of importation. 10 Some factories faced criticism and allegations of merely fitting wheels and inflating tires, resulting in scandals in the local press and on social media. This chapter ended on July 31, 2017, however vehicle imports did not resume, leading to shortages and a surge in both the new and used car sales, exacerbating unprecedented social disparities in access to cars and mobility. While the financial prosperity of the 2000s increased purchasing power and vehicle access for a substantial segment of Algerian households, the recent automotive crisis has widened the social divide in terms of mobility access.

Since 2017, Algeria has grappled with a multifaceted crisis encompassing political, economic, and health-related challenges, notably the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. This confluence of crises has impeded the progression of new specifications for the automotive industry and, by extension, the realisation of its objective to establish assembly plants with a substantial integration rate, along with fostering a robust subcontracting market to supply spare parts. The old factories have been closed. In 2023, approvals were granted to three companies (Fiat, Opel, and Jac) for a first wave of imports and to launch assembly plants by the end of the year. For instance, Fiat plans to manufacture 90,000 vehicles annually at its Oran plant, commencing operations by the end of 2023. 11

Imports resumed through dealers at the start of 2023. In addition, the decree issued on February 22, 2023, permits private individuals to import vehicles under 3 years old, subject to specific conditions: these vehicles must be tourist and commercial vehicles weighing less than 3.5 tons, with the exception of diesel engines. Customs duties and taxes can be reduced by up to "80% for electric vehicles and 50% for petrol or hybrid engines with a cubic capacity of less than 1800 cm3. This figure falls to 20% for the same types of vehicles with a cubic capacity exceeding 1800." 12

These measures are designed to prevent the market from being flooded with diesel vehicles that European countries want to get rid of. Simultaneously, they express a commitment to transforming the vehicle fleet by introducing "cleaner" vehicles and discouraging the widespread use of SUVs (vehicles with powerful engines), which currently represent a mere 3% of the current vehicle fleet. 13 Despite this, SUVs still benefit from a 20% reduction in customs duties if the vehicles are less than 3 years old.

While electric vehicles are encouraged, the charging infrastructure is still nascent. The Ministry of Energy has announced plans to install 1,000 charging stations by 2025, including 300 by 2023. 14 The national gas and electricity distribution company (Sonelgaz) oversees the national network of petrol stations, Naftal, with the first stations installed in July and August 2023.

As well as the development of electric vehicles, Algeria has embraced the widespread adoption of LPG (Liquefied Petroleum Gas), motivated by ecological and economic considerations. A 2016 report to the Prime Minister from consumer and environmental associations proposed several measures to promote LPG usage. 15 Their key argument was that, of 6 million vehicles, only 200 000 used LPG, and this in a country which is among the ten biggest exporters of gas globally. Among the recommended measures were lifting customs duties on components used in LPG equipment manufacturing, converting 100% of public institution vehicles to LPG, transitioning 30% of public and private company fleets to LPG, and making LPG service stations widely available.

In 2020, the Minister for Energy Transition and Renewable Energies, Chems Eddine Chitour, implemented some of these recommendations, mandating the widespread use of LPG in public vehicles, targeting one million vehicles by 2030. Incentives such as reductions in installation costs, payment facilities, and the abolishment of the car tax sticker were put in place. In 2022, Naftal equipped 22,000 vehicles with LPG kits. 16

While LPG is considered less polluting than other fuels 17, and Algeria is logically committed to promoting it, it remains a fossil fuel. Consequently, it sustains the country's dependence on the automotive system by shielding it from immediate reform. Nevertheless, recent decisions can be interpreted as tentative steps towards addressing greenhouse gas emissions and making the automotive system “greener”. 18

The exclusive focus on developing the automotive system at the expense of other modes of transport or the implementation of travel regulations has led to a paradoxical situation. The aspiration to bolster the local economy without relying on imports has resulted in a shortage that hampers the renewal of the aging car fleet, thereby exacerbating road safety concerns and pollution. While it may seem commendable to regulate the growth of the car fleet, the absence of viable alternatives leaves the country's mobility needs unmet.

Despite ongoing efforts to improve public transport throughout the country, particularly the railways, the measures implemented remain cautious and lack a systemic approach. Between tramway projects 19 that negotiate a coexistence with cars while negatively impacting public space and modal shift, and the recent announcement of a monorail in Algiers (Mezoued, 2023), the all-car system persists as the prevailing norm.

Figure 4: How the tramway and roadway in Constantine occupy public space to the detriment of pedestrians. Photograph by the author.

The dominance of the car system remains unchallenged 20 . A household survey conducted for Algiers in 2004 by the Algiers metro company and BETUR revealed that "56% of journeys are made on foot, compared to 44% by motorised means, including: 65% by public transport, 29% by private car, and 6% by taxi" (Chibane, 2009). These statistics pertain specifically to Algiers, and obtaining recent data is challenging. However, we do know that, since 2009, the car fleet has expanded, with imports peaking in 2012, followed by local production and subsequent deceleration. The spatial organisation of cities has been altered by numerous housing projects on the outskirts and the expansion of the road network, resulting in new commuting practices between the outskirts and urban centres (Safar-Zitoun, 2020). Public transport, on the other hand, lags behind urban growth (Mezoued, 2019) and struggles to serve new residential and employment areas. There is reason to believe that the modal share of cars has increased and is likely to rise again once the situation is resolved.

The past six years, during which the automotive system has been at a standstill, represent a missed opportunity for a sustainable transition in mobility. Indeed, Algeria may have missed a crucial window of opportunity. Despite the challenging political and economic context that may not have been conducive to significant investments in public transport, there was an opportunity to reorganise existing networks to encourage a modal shift.

And yet, paradoxically, Algeria appears to possess the capacity to influence and transform the automotive system. The deliberate halt in its development for six years to address the situation, protect its economy, and implement environmental measures indicates the country's capability for profound reforms.

While reconciling tensions between ecological transition, economic development, and the imperative to meet escalating mobility demands is undoubtedly a challenge, it is still possible to mobilise the nation's aptitude for reforms to achieve a "mobility leap." Just as the introduction of mobile phones allowed Africa to bypass the need for a landline telephone network, a mobility leap could allow Algeria to free itself from the need to go through an “all-car” stage. This would require strengthening the industrialisation of the rail sector - as was done with the streetcar assembly plants 21 -, investing significantly in the restructuring of public transport networks, and planning that accounts for urban growth. In essence, the focus should shift from a preoccupation with the automotive system to a systemic approach to mobility. Such an approach, rather than being overly fixated on a particular mode, is imperative today.

Under these conditions, it becomes conceivable to envision a mobility leap in Algeria and, potentially, in many developing countries.

Amcha, K. (2023). Infrastructure autoroutière et développement local. Échelles de structuration et opportunités de riverainisation de l’autoroute est-ouest en Algérie. Thèse de doctorat, Université catholique de Louvain

Chibane, L. (2009), La mobilité quotidienne et les transports urbains à Alger. Colloque international Environnement et transports dans des contextes différents. At: Ghardaïa, ALGERIA, Volume: Actes, ENP ed., Alger, p. 231-237. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261250673_La_mobilite_quotidienne_et_les_transports_urbains_a_Alger

Mezoued, A. (2023). Un monorail à Alger, solution miracle, ou fantasme d’un autre temps ? Blog Médiapart, consulté le 27 avril 2023 : https://blogs.mediapart.fr/aniss-m-mezoued/blog/220423/un-monorail-alger-solution-miracle-ou-fantasme-d-un-autre-temps

Mezoued, A. (2019). Le métro d’Alger et l’articulation mobilité, transport et urbanisme. Bioul, L., Declève, B. et Micic, G.(éds.) Les 40 ans du métro Bruxellois : Axes de vie – nœuds d’échanges, 266-285. Bruxelles : Bruxelles Mobilité. http://hdl.handle.net/2078.1/216449

Ravalet, E. (2014). Les infrastructures de transport font-elles le développement économique ? Forum Vies Mobile. Safar-Zitoune, M. (2020). Les mobilités urbaines à Alger : un état des lieux de la recherche sociologique. Forum Vies Mobiles : Carnet des Suds.

2 By way of comparison, on the 1st of January, 2019, France had 40 million vehicles for 67 million inhabitants: https://www.statistiques.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/2019-04/2019-parc-vehicules-routiers-0pf1.xls

3 https://www.algerie-expat.com/economie/lalgerie-a-besoin-dun-million-de-voitures-neuves/28308/

5 Algeria is divided into 58 local authorities known as Wilayas.

6 Algeria's geography comprises, from north to south: the Tell (coastline), the Tellian Atlas mountain range, the High Plateaus, the Saharan Atlas range, then the Sahara.

7 New partnership for Africa's development

9 The proportion of components used in assembly that are manufactured locally.

12 Source : El Watan daily newspaper, Sunday 9 April 2023. Interview with Mohamed Yaddadène, automotive consultant.

13 Idem.

14 https://www.algerie360.com/voitures-electriques-300-bornes-de-recharge-bientot-en-algerie/

15 https://algeriesolidaire.net/une-association-plaide-pour-le-renforcement-de-lutilisation-du-gpl/

16 The LPG kit is a gas canister usually installed in the trunk of the car or in place of the spare tire and connected to the engine. https://www.aps.dz/economie/153193-commercialisation-du-gpl-naftal-a-depasse-les-objectifs-fixes

17 https://www.auto-moto.com/actualite/environnement/gpl-le-moins-polluant-des-carburants-61601.html et https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590162122000405

18 The point is to avoid ending up with the second-hand, polluting vehicles that are banned in Europe.

19 7 tramway lines operate in Algiers, Constantine, Oran, Sidi Bel Abbès, Ouargla, Sétif and Monstaganem. Two lines are under construction in Annaba and Batna, and many more are planned for Béchar, Béjaïa, Biskra, Blida, Bouira, Chlef, Djelfa, Jijel, Mascara, M'Sila, Relizane, Skikda, Souk-Ahras, Tébessa, Tiaret and Tlemcen.

20 Few reliable studies exist on the modal shares of Algerian mobility. The last population census carried out at the end of 2022 is still not available at the end of 2023.

21 https://radioalgerie.dz/news/fr/article/20151224/62405.html

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xLifestyles

Southern Diaries by Forum Vies Mobiles are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 France License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at contact.

Other publications