29 March 2017

Like in many African cities, Nairobi’s minibuses are an informal mode of collective transportation that emerged due to a lack of efficient public transportation. As in many other cities, the latter ultimately disappeared as a result of competition from this type of minibus, which offers residents travel options in the form of fragmented collective transport services. Economic crises and the liberalization of the sector underlie the emergence of this system.In this context, this informal system meets both mobility and employment needs.

04/11/17

In the majority of African cities, minibuses, collective taxis and motorcycle taxis zigzag through the streets in search of passengers, occasionally respecting hypothetical bus stops. Informal transportation takes different forms depending on the city. Minibuses can be found from Jakarta to Lima, and from Brazzaville to Nairobi, whereas motorcycle taxis are increasingly popular in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in Cotonou and Lomé. Whatever their configuration, informal transportation unarguably provides mobility solutions to a large portion of the population. Nonetheless it is often regarded as archaic and outdated. Effectively, the sector’s economic model often gives prominence to the competition and apparent disorganization. The lack of maps and schedules, the aging vehicles and the air/noise pollution are part of this outdated image. In the collective imagination, however, informal transportation opposes the model of modernity and development of centralized, highly-regulated, European transportation systems spread by official discourse. Informal transportation systems are poorly documented; travelers use word of mouth to plan their journeys, as comprehensive knowledge of the transportation system is inexistent. The lack of a database is also problematic for public authorities desirous to formalize or regulate the sector.

Yet today, informal collective transportation still enables the daily mobility of millions of city dwellers throughout the world. The variety of situations is undeniable. However, as we will see taking the case of matatus , the outdated nature of informal collective transportation can be questioned. The use of buses as a means of cultural and artistic expression, along with the growing use of new technologies, has given rise to a new form of modernity in informal collective transportation.

Today, the Kenyan capital of Nairobi is facing a number of traffic problems. Since the economic crisis and liberalization of transportation in 1973, matatus have been the dominant mode of transportation for the majority of the city’s 3 million inhabitants, more than half of whom are under 20 1. The 15-seat minibuses’ decor is highly personalized, with artwork, fluorescent tubing, powerful sound systems and screens. The name matatu comes from the Swahili tatu, which means "three": when the service first appeared, the trip fare was equivalent to three 10-cent coins.

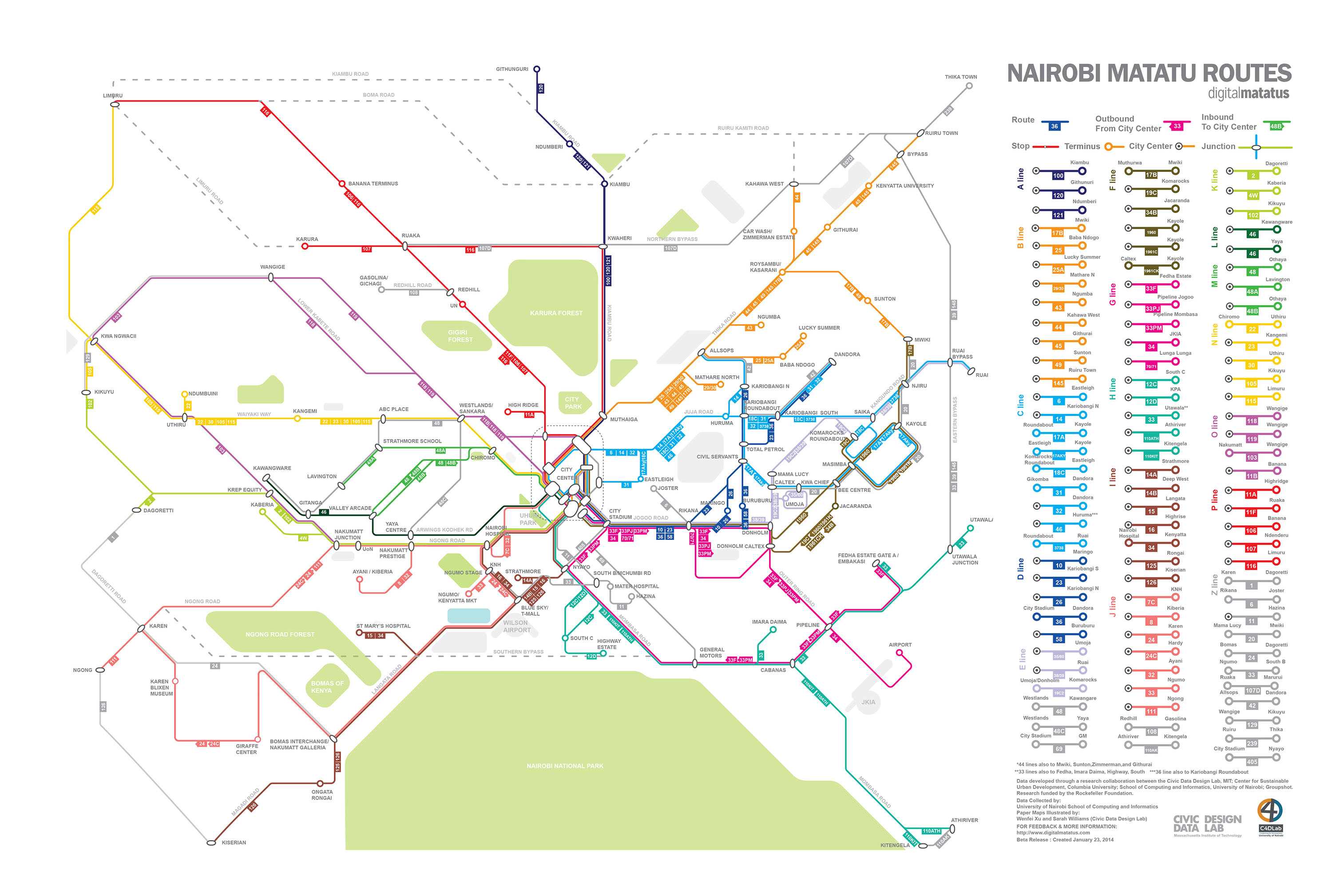

The sector is comprised of small owners and self-employed workers who provide services using more or less well-maintained minibuses. Matatus operate on the 135 lines inherited from the former public transportation system 2 as well as on new itineraries created as and when needed. Actually, routes are constantly being modified (in order to avoid traffic congestion or police checks, for example). As such, it can be difficult for users to orient themselves, which is why the crier plays a key role. Called manamba 3 in Nairobi, criers, who are present in nearly all informal transportation systems, announce the vehicle destination and try to attract users.

Matatus function like many informal transportation systems. Owners of minibuses rent their vehicles to drivers who then enlist criers. Matatu men are mostly men under 40 for whom the informal transportation system offers a veritable employment solution. Contrary to the rather negative image of informal workers in the 1980s, Matatu men today are regarded as true entrepreneurs.

Without data on matatu users, it is unclear whether their practices differ from those of users in other African cities. Foot travel is also an important mode, and complementary to the use of informal collective transportation modes, which are not used by the very poor as their fares are prohibitive, nor by more affluent classes who can afford other motorized means.

Matatus are a societal phenomenon that go beyond the mere question of collective transportation, given their contact with the majority of the population and their role as a nexus for many phenomena. It is not surprising then that, for this reason, they served as spearheads for protests against the political regime in the 1990s, broadcasting protest songs and enabling rallies and demonstrations including the saba-saba riots that shook the establishment.

Another feature makes matatus an original example in the informal collective transportation landscape. Ever since they appeared, drivers have personalized their matatus , thus making them a means of artistic expression. More or less fashionable, they sport the colors of popular football teams or fashionable brands. The mchongoano - popular poetic and/or humoristic expressions - blossom in the mouths of criers or in the form of stickers. The vehicles are decorated by local artists, who draw inspiration from major icons of global culture. The music broadcast by the powerful sound systems is in keeping with the theme. Matatus are thus a coherent whole that results from a collective creative process, a place where trends and arts are created in a variety of forms..

Minibuses are places of exchange and creativity, but also of identification. Vehicles may show their support for a particular football team, style of dress or political position. Users take this parameter into account in their choice of matatus : some, for example, might choose the PSG matatu over the FC Barcelona one. Beyond these fads, matatus are particularly comfortable and well-equipped for informal collective transportation. Some have screens that broadcast videos and/or WIFI connections. Matatus could be considered as a luxury transport compared to the vehicles in other informal systems.

The need to produce reliable data for users, transporters or urban planners, is increasingly pressing, especially in large cities where the system’s size exceeds the capacity of word-of-mouth communication. At the same time, the spread of new technologies, particularly smartphones, makes informal transportation’s entry into the 2.0 era both possible and necessary. National and international development projects are coordinated around the promotion of new technologies (network, technology clusters in partnership with Silicon Valley, etc.) and are part of the national strategy — Kenya Vision 2030 4. In parallel to these major projects, the use of ICT increased significantly in Kenya, with Internet penetration reaching 47.3% and nearly 20 million smartphones in 2010 5. Matatus have seized these new technological opportunities, and Nairobi is now at the forefront of informal transportation in the digital age.

City dwellers in the Kenyan capital now have a number of applications available to them for optimizing their travel. These applications use data from the Digital Matatus research project, a database enriched and updated in real time by users' contributions, among other sources. The research project, headed by Kenyan and American universities, aims to build a matatu database, a project that would not have been possible had Kenya not recently experienced an ICT breakthrough. Indeed, smartphones equipped with geolocation enabled the investigative team to collect specific information and format it so as to be reusable.

A collective transportation map of Nairobi is also now available. Moreover, all the data is in open access and is being used to develop a set of smartphone applications that are in constant evolution. Today we find several types of services for visualizing the state of traffic (notably matatus ), locating bus stops and lines close to users, and calculating routes between two stops. Users can edit the data to help improve service. Some matatus are even connected to this application and use it to update constantly their position and destination. Users can thus follow the movements of their favorite buses. Additionally, Google Maps has integrated the Digital Matatus data, and the calculated routes also include a "public transportation" option.

The emergence of new technology in the informal transportation sector is also an opportunity to improve the latter’s image. This technological leap forward is a small revolution in the world of informal collective transport, despite the lack of centralization. Although no intervention by public authorities or any other regulatory body has been made, the sector nonetheless has all the aspects of an institutionalized system: itineraries and schedules have been clarified and communication facilitated. Rather, it is a 2.0 form of regulation - or self-regulation - of the system.

The case of Nairobi is still unique in the landscape of informal transportation in Africa, and the socio-economic impact of these new practices remains relatively unstudied. These innovations seem to be a fruitful cross between new technologies and practices; the added value of marketing for matatus seems important. One can also imagine many advantages for users, particularly in terms of system readability. However, new technology seems to serve here as a catalyst for existing phenomena. Indeed, the specificity of matatus, i.e. the artistic and social dimensions of the phenomenon, far precedes the use of smartphones. While Kenya may be the leader in the development of new technologies and the spread of mobile phones with Internet access, the reproducibility of this type of phenomenon elsewhere on the continent depends on the development of infrastructure and the spread of innovation. Urban growth, however, is making the usual, or traditional functioning of informal transportation difficult. All the more, Nairobi’s international status required that it improved the readability of its collective transportation system for new users. When the population of a city exceeds several million inhabitants, data production and access to information is crucial for the smooth functioning of the transportation system. What François Ascher calls the "soft" of transportation (by computer analogy and as opposed to the "hard" of infrastructures) could find promising support herein.

Increased motorized mobility is not a sustainable solution for many reasons that we will not specify here. This process was notably observed in North America and Europe in the 20th century, with the massive spread of the automobile. Informal collective transportation is currently present in contexts with a low motorization rate 6. Moving this bus system into the digital age as the means of achieving a mobility transition in countries with low motorization rates could offer an alternative to increasing the numer of individual cars. These countries would avoid, or at least help to mitigate, car dominance and its negative externalities. Looking further ahead, we can envisage the use of electric buses (and accompanying infrastructure) through national or international subsidies, or private investments.

Indeed, this new mode of collective transportation could help to cause a shift towards smoother, more sustainable daily mobility. By combining informal transportation and new technology, matatus are an innovation whose spread will be interesting to observe. This system gives digital structure to informal transportation while maintaining flexibility due to the lack of centralization. The use of new technology and the personalized vehicles make this mode trendy and accessible, especially among young people — a potentially credible alternative to the individual car?

The low motorization rate naturally influences the "popularity" of matatus and the use of informal transportation in general. The transfer of such alternative modes to contexts where individual car ownership is facilitated raises serious questions. The artistic dimensions, personalization of the vehicles or technophile outfittings alone are not sufficient incentive for a modal shift. Nevertheless, those features could be combined with added innovative flexibility to the planned, rigid public transportation services of North countries.

The modeling of a collective taxi service similar to informal transportation has shown promising results. In the case of Lisbon, the use of more flexible, connected public transportation would, among other things, reduce CO2 emissions, improve accessibility and generate considerable financial and space savings. It remains to be seen how this type of organization can be developed.

Ubers and the UberPool carpool option might initially appear as a solution. However, the economic and social characteristics of this system are not sustainable and rather are a reflection of a logic of profit and the exploitation of drivers, and as such does not correspond to the inclusive vision of a flexible transportation system.

Finally, two convergent movements can be observed: the increase in connections within an already flexible transportation system in Nairobi’s case and the flexibilization of an already connected transportation system in Lisbon. Flexibility and connection could serve as two pillars in a sustainable (r)evolution of collective transportation in both Souths and Norths.

© Pictures by Cyrill Villemain

Available on the Internet:

1 The 2009 census effectively showed that 54% of the 44.3 million Kenyans are under 20.

2 This transportation system was managed by a private British company in partnership with the city hall. The Kenya Bus Service saw its monopoly disappear in 1973 with the matatu legalization. It eventually closed its doors due to increasing competition and economic difficulties linked notably to the State’s divestiture.

3 Crier in Swahili.

4 This governmental program, launched in 2008, aims to favor industrialization and improve the quality of life in Kenya. The development policy is based on initiatives from the economic, political and social sectors.

5 Given that Internet use is accessible on average to 28% of the population of African countries, Kenya is a leader in this area (Internet World Stats).

6 Motorization rates by continent (in vehicles per 1,000 inhabitants) are as follow: 644 for North America, 559 for Europe, 534 for Japan and Korea, 241 for Eastern Europe, 142 for South America, 62 for Southeast Asia and 41 for Africa. These figures are an average estimate by the World Bank (2010). They are used to represent the present situation, given the current sharp rise in the motorization rate in Africa.

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus x

Southern Diaries by Forum Vies Mobiles are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 France License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at contact.

Other publications