13 October 2017

Have you ever considered the massive importance that mobility plays in determining young people’s lives and life chances? Given the crucial role of transport, could practitioners’ and policy makers’ interventions in this arena help change young lives for the better?

Have you ever considered the massive importance that mobility plays in determining young people’s lives and life chances? Given the crucial role of transport, could practitioners’ and policy makers’ interventions in this arena help change young lives for the better? My aim in this short piece is not only to draw your attention to the central role that mobility plays in young people’s lives in sub-Saharan Africa, but also to make some suggestions regarding what could be done to help improve those lives. Much of this draws on a book I have written called Young people's daily mobilities in sub-Saharan Africa: Moving young lives. For me this has been a labour of love, because it’s enabled me to reflect on transport and mobilities work I’ve been conducting over the last 40 years across Africa, in collaboration with various teams of (mostly African)academic researchers).

I started my research on transport and mobilities as a young lecturer at the (newly established) University of Maiduguri in the mid-1970s: in this remote north-east corner of Nigeria, I quickly discovered that transport (or lack of it) was key to understanding how lives and livelihood opportunities were shaped, especially for women and girls. Over subsequent years, attention to women’s mobility as a development factor in Africa greatly expanded but children’s mobility, by contrast, remained a neglected topic. Since over half of the population of many African countries consists of children and young people under the age of 15, and so little is known about the daily mobility and mobility constraints that help shape their lives and life chances, the justification for more work in this field was obvious.

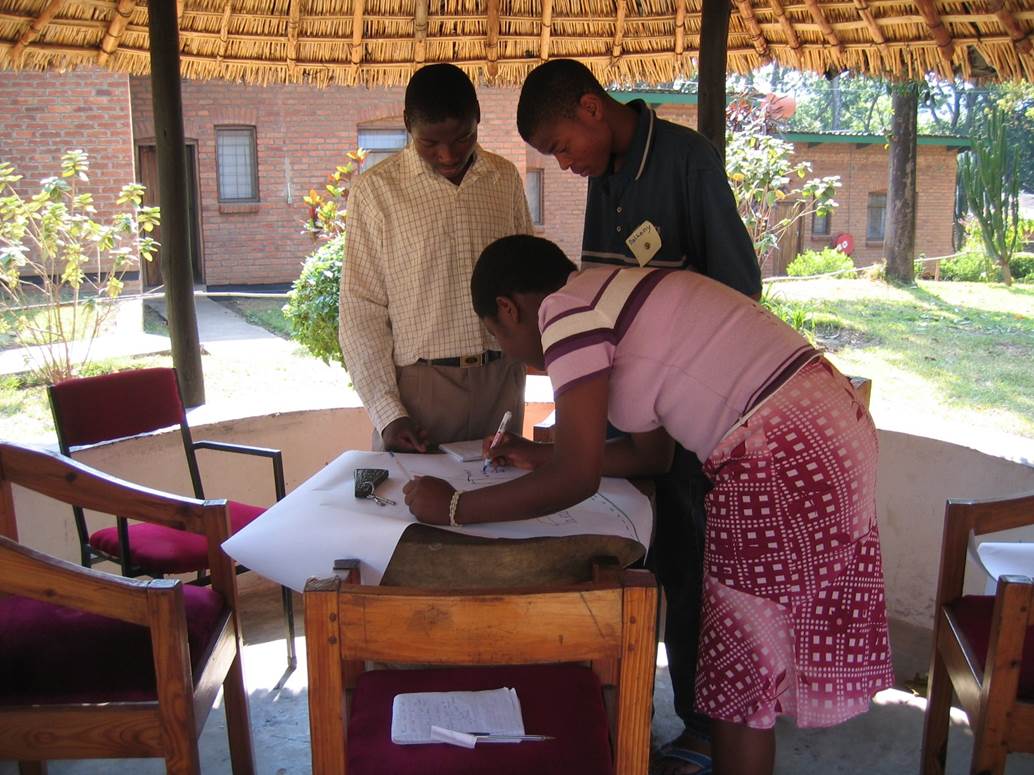

Much of the mobilities work I have undertaken has been with academic collaborators in Africa, especially staff at the University of Cape Coast (Ghana), but as our efforts to gain a deeper understanding of young people’s mobile lives and how they unfold gathered pace, we started to experiment with working with young school pupils directly, training them as co-researchers. Eventually, this enabled us to recruit seventy young school pupils as co-investigators. They have helped us to move far beyond the bare facts of stasis or movement from place to place, or the direct economic factors which shape mobility potential, to a deeper understanding of the lived experiences of the boys and girls making those journeys in urban and rural Africa, and the politics of mobility within which their journeys are set.

Gender is of critical significance in this respect: it not only moulds the specific shape and experiences of many of the journeys, but can also massively influence future lives and life chances; not least, the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage. To give one telling example, delayed entry to school because of distance and parental perceptions of a daughter’s travel vulnerability in rural Africa is often followed by early drop out, especially when even lengthier journeys would be required for her to reach secondary school. The impacts may extend well beyond that girl’s likely very poor job options, to affect her (high) fertility rate and child-rearing practices, all with implications for child health, survival and schooling patterns in the next generation. Take Susanna in remote rural Malawi, for instance, who only started school at the age of 9 because it was so far from home. She dropped out at after a few years because ‘the school was just too far for me to be walking every day’. She has undertaken paid, casual work such as carrying heavy loads of firewood and loads of water for house-builders in the village, since the age of 10, and continued with this all through her short school life. She is now 20 with little prospect except marriage, child-bearing and a continuing arduous life of casual labouring.

Such gendered politics of mobility cannot be ignored. Gender inequalities and fear of gender-based violence are key to many of the mobility decisions made by, and for, girls. They seem to be inextricably bound up with a crisis of masculinities, particularly strongly evident in southern Africa. By this, I mean the way changes in social and economic conditions are making some men very uncertain about their social role and identity 1. Community dialogue and associated training will be essential for the resolution of that crisis and, while this is a growing focus of NGO activity, the task is massive and likely to take many years.

In the meantime, there are some smaller steps with potential to improve young people’s mobile lives, some specifically focused on transport arrangements, but many others requiring a more holistic, cross-sectoral approach. In many of these contexts, of course, it is clear that less rather than more mobility would be advantageous (a denser network of school and health centres, and piped water to compounds to avoid frequent repetitive trips to collect water, for example). Unfortunately, in many cases the investment entailed in that level of infrastructure provision will not be available for some time.

In the meantime, here are some suggestions for policy interventions that could help improve young lives, especially girls’ lives and life chances:

The findings presented here draw on my early mobilities research in Nigeria, South Africa and Ghana and subsequent work I have conducted across diverse sub-Saharan African countries. It draws, in particular, on recent research from the three country study I led in poor communities across Ghana, Malawi and South Africa with in-country collaborators at the Universities of Cape Coast (Ghana), Malawi and South Africa’s CSIR. This latter project has provided an enormous reservoir of information by triangulating young people’s voices (gathered through in-depth interviews, focus groups and life histories) with a major survey of 3000 young people aged 9-18 years, living in 24 poor urban and rural settlements. Because walking figures prominently in young people’s mobility, much of the information comes from interviews we conducted on the move, walking alongside young people as they travelled to or from school, market, water point, forest reserve, even video houses: as a journey unfolds this can often bring crucial insights into individual experiences of exhaustion, boredom, fear or fun.

The publication presenting this research includes empirical evidence for different kinds of journeys: children’s journeys to school, journeys to and within work contexts (including journeys carrying heavy loads), journeys for play and leisure (where mobile phones increasingly allow virtual mobility, leapfrogging physical space), and for accessing health services. In each case, comparisons are drawn between urban and rural contexts, and across countries. This is followed by chapters covering specific modes: walking, cycling, and motor mobility, including critical experiences around traffic risk and road safety.

For further information about my work, please click here, or get in touch with me at r.e.porter@durham.ac.uk. I’m also very keen to hear about other ongoing work in this area.

1 This may be linked not only to the impact of Neoliberal economic policies which have created hardship for many Africans, but also in some cases to a growing focus on women’s empowerment in development interventions. Some young, poor men have experienced marginalisation, for example, with shifts in domestic power relations as more women enter the labour force.

For the Mobile Lives Forum, mobility is understood as the process of how individuals travel across distances in order to deploy through time and space the activities that make up their lifestyles. These travel practices are embedded in socio-technical systems, produced by transport and communication industries and techniques, and by normative discourses on these practices, with considerable social, environmental and spatial impacts.

En savoir plus xMovement is the crossing of space by people, objects, capital, ideas and other information. It is either oriented, and therefore occurs between an origin and one or more destinations, or it is more akin to the idea of simply wandering, with no real origin or destination.

En savoir plus xTheories

Southern Diaries by Forum Vies Mobiles are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 France License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at contact.

Other publications