Contact

- For any questions regarding a Forum research project, please contact the project manager whose name is indicated on the page (see the “Project” section)

- For any questions regarding an event, one of our books or the valuation of a project, please contact Tom Dubois

- For press relations please, contact Véronique Wasa or consult our Press page

- To add an event to the calendar, please contact Thomas Evariste

- To submit a new book for the section "New in the library", please contact Thomas Evariste.

- For any other questions, please contact Sylvie Landriève

Subscribe to the newsletter

Subscribe to the newsletter

Fig1. Design principles of The Line.

Within the country, the Vision 2030 initiative is equally well-promoted through a multitude of projects of varying scales across the nation. This time, the focus is on improving the quality of life for Saudi citizens, with the specific goal of ranking three Saudi cities—including Riyadh and Jeddah—among the top 100 cities globally for quality of life.

Fig1. Design principles of The Line.

Within the country, the Vision 2030 initiative is equally well-promoted through a multitude of projects of varying scales across the nation. This time, the focus is on improving the quality of life for Saudi citizens, with the specific goal of ranking three Saudi cities—including Riyadh and Jeddah—among the top 100 cities globally for quality of life.

Fig.2. Vision 2030 logo

These projects are gradually taking shape, often in the middle of the desert, in a country grappling with the severe effects of climate change. With increasingly extreme temperatures and long-standing water scarcity, the stakes are enormous. Saudi Arabia appears to have acknowledged these challenges, setting an ambitious target of achieving "net zero emissions" by 2060. This represents a monumental task for a nation that consistently ranks among the top ten global emitters of carbon dioxide per capita.

It is within this context that the Mobile Lives Forum took a closer look at mobility in the oil kingdom. The investigation began with an analysis of ongoing projects, evaluating their relevance to sustainable mobility and their impact on shifts in travel habits, particularly regarding automobile use. The study then broadened to examine the more systemic lifestyle transformations accompanying economic and societal reforms, all viewed through the lens of mobility. Special attention was given to citizens' perceptions of these changes, especially the role of public transportation projects and their effects on the use of urban spaces across different social groups. Another key focus was the integration of "local living" within these projects and the strategies being developed to adapt to extreme climatic conditions, particularly in light of global environmental changes.

To address these questions, the Mobile Lives Forum organized a study trip in late April 2024, in order to engage with researchers and mobility professionals. Preliminary bibliographic research had revealed a notable lack of studies on everyday mobility in Saudi Arabia, aside from numerous works on traffic and road safety. This led to the identification of key researchers and institutions for further engagement.

Three cities were chosen as study sites for their dynamic mobility transformations: Riyadh, Dammam, and AlUla. The selection aimed to provide insights from cities of varying sizes.

The research focused on daily mobility, deliberately excluding exceptional cases related to religious pilgrimage. Brief one-day visits to Medina, Mecca, and Jeddah offered a general overview of these major cities but did not involve formal meetings.

Fig.2. Vision 2030 logo

These projects are gradually taking shape, often in the middle of the desert, in a country grappling with the severe effects of climate change. With increasingly extreme temperatures and long-standing water scarcity, the stakes are enormous. Saudi Arabia appears to have acknowledged these challenges, setting an ambitious target of achieving "net zero emissions" by 2060. This represents a monumental task for a nation that consistently ranks among the top ten global emitters of carbon dioxide per capita.

It is within this context that the Mobile Lives Forum took a closer look at mobility in the oil kingdom. The investigation began with an analysis of ongoing projects, evaluating their relevance to sustainable mobility and their impact on shifts in travel habits, particularly regarding automobile use. The study then broadened to examine the more systemic lifestyle transformations accompanying economic and societal reforms, all viewed through the lens of mobility. Special attention was given to citizens' perceptions of these changes, especially the role of public transportation projects and their effects on the use of urban spaces across different social groups. Another key focus was the integration of "local living" within these projects and the strategies being developed to adapt to extreme climatic conditions, particularly in light of global environmental changes.

To address these questions, the Mobile Lives Forum organized a study trip in late April 2024, in order to engage with researchers and mobility professionals. Preliminary bibliographic research had revealed a notable lack of studies on everyday mobility in Saudi Arabia, aside from numerous works on traffic and road safety. This led to the identification of key researchers and institutions for further engagement.

Three cities were chosen as study sites for their dynamic mobility transformations: Riyadh, Dammam, and AlUla. The selection aimed to provide insights from cities of varying sizes.

The research focused on daily mobility, deliberately excluding exceptional cases related to religious pilgrimage. Brief one-day visits to Medina, Mecca, and Jeddah offered a general overview of these major cities but did not involve formal meetings.

Fig. 3. View of Riyadh

Fig. 3. View of Riyadh

Fig. 4. View of a street in Dammam

Fig. 4. View of a street in Dammam

Fig.5. View of the old town and the palm grove of AlUla.

Fig.5. View of the old town and the palm grove of AlUla.

Fig 6. Car cult in the streets of Riyadh. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

The mobility system in Saudi Arabia is evolving alongside broader changes in society and the economy. Efforts to prepare for a post-oil economy by creating a "modern" economic framework include reducing subsidies and introducing value-added taxes. As a result, fuel prices have been rising since 2018, along with the cost of certain vehicles.

These economic shifts, combined with profound societal changes and significant investments in public transport, public spaces, and various infrastructure projects, are driving radical changes in the travel behaviors and lifestyles of Saudi men and women.

Fig 6. Car cult in the streets of Riyadh. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

The mobility system in Saudi Arabia is evolving alongside broader changes in society and the economy. Efforts to prepare for a post-oil economy by creating a "modern" economic framework include reducing subsidies and introducing value-added taxes. As a result, fuel prices have been rising since 2018, along with the cost of certain vehicles.

These economic shifts, combined with profound societal changes and significant investments in public transport, public spaces, and various infrastructure projects, are driving radical changes in the travel behaviors and lifestyles of Saudi men and women.

Fig. 7. Territorial development plan 2030. (IPR, 2021).

To achieve these goals, Saudi Arabia is embracing economic openness to the international market. This strategic shift is accompanied by significant social and economic reforms, including closer ties with Northern countries, enhanced women's rights, the privatization of various sectors, and efforts to attract international tourism. Central to this vision is the call for Saudi citizens to actively participate in the evolving economy through employment-focused initiatives. A major aspect of this transformation is "Saudization," or Nitakat in Arabic, a strategy aimed at reducing unemployment in a workforce where foreigners make up 41% of the population. Under this policy, companies—both Saudi and foreign—are incentivized to meet specific quotas for Saudi employees. The higher the percentage of Saudi nationals in a company’s workforce, the greater the benefits the company receives.

Among all the societal and territorial changes, Saudization is perhaps the most likely to rapidly influence mobility, particularly in terms of automobile usage. This transformation is already evident, especially with the increasing participation of women in the workforce, in a context where public transport was previously minimal or nonexistent. Changes in family structures and employment dynamics have coincided with two landmark events: the 2018 decision granting women the right to drive and the imposition of higher taxes on foreign workers. These taxes, amounting to 400 rials per dependent per month, have made employing private drivers more challenging, accelerating shifts in mobility practices.

Even before the tax, not all Saudis could afford private drivers, and many still drive themselves. This was evident in interviews with more than 30 Uber drivers during the study trip. Over 90% of them were Saudis, unlike traditional taxi companies that predominantly employ foreign drivers. When asked about their motivations, most drivers highlighted the enjoyment of meeting new people, followed by the benefit of supplementary income. Many drivers have primary jobs alongside their Uber work—for example, one driver, Saoud, mentioned he is also a school principal. Uber’s presence in Saudi Arabia has grown steadily, with over 530,000 trips recorded between its launch in 2014 and 2021. Similarly, delivery companies are experiencing rapid growth, fueled by the increasing popularity of online shopping and digital payments. Some institutions, such as King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals (KFUPM) in Dhahran, have even developed their own internal delivery services and proprietary ordering applications to cater to their communities.

Fig. 7. Territorial development plan 2030. (IPR, 2021).

To achieve these goals, Saudi Arabia is embracing economic openness to the international market. This strategic shift is accompanied by significant social and economic reforms, including closer ties with Northern countries, enhanced women's rights, the privatization of various sectors, and efforts to attract international tourism. Central to this vision is the call for Saudi citizens to actively participate in the evolving economy through employment-focused initiatives. A major aspect of this transformation is "Saudization," or Nitakat in Arabic, a strategy aimed at reducing unemployment in a workforce where foreigners make up 41% of the population. Under this policy, companies—both Saudi and foreign—are incentivized to meet specific quotas for Saudi employees. The higher the percentage of Saudi nationals in a company’s workforce, the greater the benefits the company receives.

Among all the societal and territorial changes, Saudization is perhaps the most likely to rapidly influence mobility, particularly in terms of automobile usage. This transformation is already evident, especially with the increasing participation of women in the workforce, in a context where public transport was previously minimal or nonexistent. Changes in family structures and employment dynamics have coincided with two landmark events: the 2018 decision granting women the right to drive and the imposition of higher taxes on foreign workers. These taxes, amounting to 400 rials per dependent per month, have made employing private drivers more challenging, accelerating shifts in mobility practices.

Even before the tax, not all Saudis could afford private drivers, and many still drive themselves. This was evident in interviews with more than 30 Uber drivers during the study trip. Over 90% of them were Saudis, unlike traditional taxi companies that predominantly employ foreign drivers. When asked about their motivations, most drivers highlighted the enjoyment of meeting new people, followed by the benefit of supplementary income. Many drivers have primary jobs alongside their Uber work—for example, one driver, Saoud, mentioned he is also a school principal. Uber’s presence in Saudi Arabia has grown steadily, with over 530,000 trips recorded between its launch in 2014 and 2021. Similarly, delivery companies are experiencing rapid growth, fueled by the increasing popularity of online shopping and digital payments. Some institutions, such as King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals (KFUPM) in Dhahran, have even developed their own internal delivery services and proprietary ordering applications to cater to their communities.

Fig. 8. KFUPM delivery service. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

Fig. 8. KFUPM delivery service. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

Fig. 9. Delivery services in Riyadh. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

The complete digitalization of administrative services has significantly reduced the need for "bureaucratic" travel, according to Professor Ratrout of KFUPM. Administrative documents are now fully digital or delivered directly to homes. While this has certainly reduced the physical movement of people, it has likely increased the flow of goods and deliveries, as well as the precarity of certain segments of the population, as has been observed elsewhere[^1].

In Riyadh, most drivers we interviewed lived in the southern districts and often came from other regions of Saudi Arabia or, in some cases, neighboring countries. This points to the emergence of a distinct social geography within Saudi cities. However, the issue of socio-spatial segregation is rarely, if ever, addressed in major projects and remains largely taboo. The residential areas of immigrant workers, for instance, are invisible in urban planning discourse, and no official communication appears to tackle this sensitive topic. In The Line project, which touts itself as a visionary development, we were unable to obtain concrete details about where the workers who will sustain the city are expected to live. The only information we gathered is that on the construction sites, there is already a marked separation between the camps of laborers and those of Saudi or foreign managers. These socio-spatial dynamics inevitably raise critical questions about mobility, accessibility, and equal opportunities. They are deeply tied to the effects of Saudization and its broader systemic impact on Saudi society.

Fig. 9. Delivery services in Riyadh. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

The complete digitalization of administrative services has significantly reduced the need for "bureaucratic" travel, according to Professor Ratrout of KFUPM. Administrative documents are now fully digital or delivered directly to homes. While this has certainly reduced the physical movement of people, it has likely increased the flow of goods and deliveries, as well as the precarity of certain segments of the population, as has been observed elsewhere[^1].

In Riyadh, most drivers we interviewed lived in the southern districts and often came from other regions of Saudi Arabia or, in some cases, neighboring countries. This points to the emergence of a distinct social geography within Saudi cities. However, the issue of socio-spatial segregation is rarely, if ever, addressed in major projects and remains largely taboo. The residential areas of immigrant workers, for instance, are invisible in urban planning discourse, and no official communication appears to tackle this sensitive topic. In The Line project, which touts itself as a visionary development, we were unable to obtain concrete details about where the workers who will sustain the city are expected to live. The only information we gathered is that on the construction sites, there is already a marked separation between the camps of laborers and those of Saudi or foreign managers. These socio-spatial dynamics inevitably raise critical questions about mobility, accessibility, and equal opportunities. They are deeply tied to the effects of Saudization and its broader systemic impact on Saudi society.

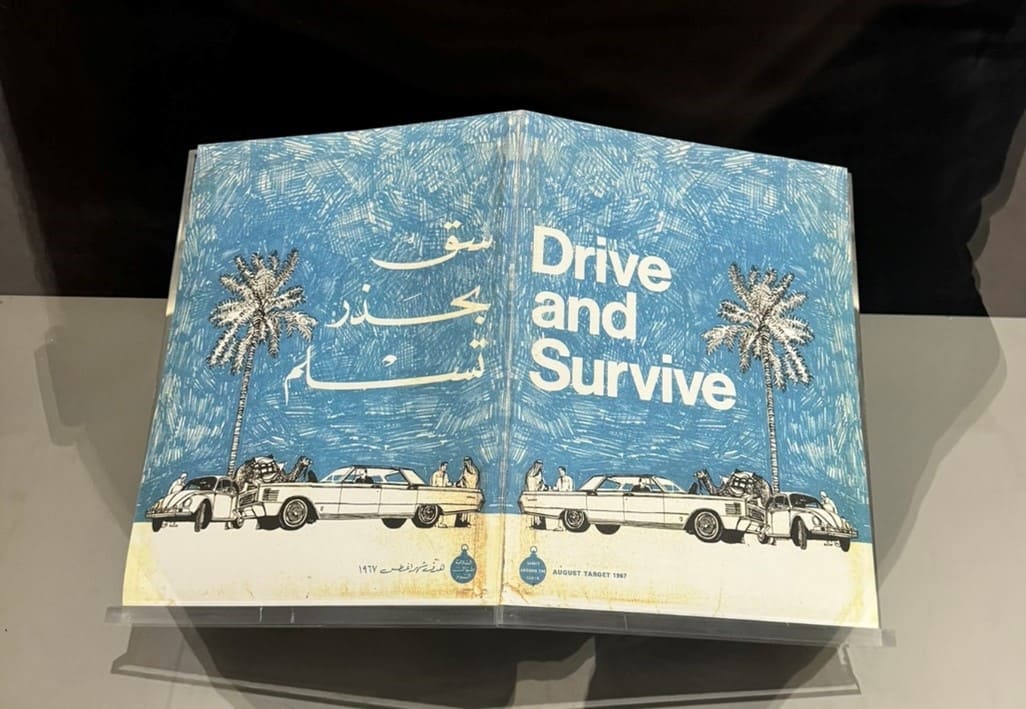

Fig. 10. Road safety awareness magazine “Drive and Survive”, produced by ARAMCO to “instill the culture of safety in the population”. Source: ARAMCO Museum, Dammam. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

While the shift to electric vehicles remains challenging in Saudi Arabia—where charging infrastructure is still in its infancy and gasoline costs less than 2 SAR (50 cents) per liter—public transport seems poised to gain a foothold. This shift is closely tied to the overarching goal of improving quality of life, a key driver behind the ongoing transformations. Enhancing the quality of public spaces and expanding public transport offerings are central pillars of this effort. The lifestyle changes brought about by "Saudization" are likely to increase the volume of trips, many of which could be accommodated by alternative modes of transport currently being developed. Monumental investments are underway to transition cities from a car-dominated model to a viable, multimodal system. However, this transformation is starting from near-zero: public transport currently accounts for just 1–2% of the modal share and is primarily used by foreign workers via company-chartered buses. In the three cities studied, there were no formal bus networks until recently, let alone metro systems, trams, or pedestrian-friendly sidewalks.

Without directly challenging the dominance of cars, the kingdom is making substantial investments in creating a diverse range of mobility options. The strategy, as promoted by some stakeholders, is to establish a visible presence of public transport in urban spaces. This includes offering high-quality services that provide added value compared to individual car use, whether in terms of cost or travel time, and encouraging gradual adoption through personal experimentation. The redistribution of public space and a potential reduction in the prominence of cars may only emerge in later stages of this process.

Fig. 10. Road safety awareness magazine “Drive and Survive”, produced by ARAMCO to “instill the culture of safety in the population”. Source: ARAMCO Museum, Dammam. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

While the shift to electric vehicles remains challenging in Saudi Arabia—where charging infrastructure is still in its infancy and gasoline costs less than 2 SAR (50 cents) per liter—public transport seems poised to gain a foothold. This shift is closely tied to the overarching goal of improving quality of life, a key driver behind the ongoing transformations. Enhancing the quality of public spaces and expanding public transport offerings are central pillars of this effort. The lifestyle changes brought about by "Saudization" are likely to increase the volume of trips, many of which could be accommodated by alternative modes of transport currently being developed. Monumental investments are underway to transition cities from a car-dominated model to a viable, multimodal system. However, this transformation is starting from near-zero: public transport currently accounts for just 1–2% of the modal share and is primarily used by foreign workers via company-chartered buses. In the three cities studied, there were no formal bus networks until recently, let alone metro systems, trams, or pedestrian-friendly sidewalks.

Without directly challenging the dominance of cars, the kingdom is making substantial investments in creating a diverse range of mobility options. The strategy, as promoted by some stakeholders, is to establish a visible presence of public transport in urban spaces. This includes offering high-quality services that provide added value compared to individual car use, whether in terms of cost or travel time, and encouraging gradual adoption through personal experimentation. The redistribution of public space and a potential reduction in the prominence of cars may only emerge in later stages of this process.

Fig. 11. First bus lines and stops along Olaya Street, Riyadh. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

Fig. 11. First bus lines and stops along Olaya Street, Riyadh. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

Fig. 12. Iconic King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD) station designed by Zaha Hadid. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

In terms of achieving a modal shift, authorities aim to attract 1.2 million daily passengers to the metro system, which will serve as the backbone to the supporting bus network, increasing the overall figure to 1.7 million passengers. According to the Royal Commission for Riyadh City (RCRC), the full deployment of the network has the potential to accommodate up to 3.6 million daily trips. The overarching goal is to reduce the number of cars on Riyadh's streets. The integrated network will connect passengers to airports, public services, major universities, and Riyadh East train station.

Fig. 12. Iconic King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD) station designed by Zaha Hadid. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

In terms of achieving a modal shift, authorities aim to attract 1.2 million daily passengers to the metro system, which will serve as the backbone to the supporting bus network, increasing the overall figure to 1.7 million passengers. According to the Royal Commission for Riyadh City (RCRC), the full deployment of the network has the potential to accommodate up to 3.6 million daily trips. The overarching goal is to reduce the number of cars on Riyadh's streets. The integrated network will connect passengers to airports, public services, major universities, and Riyadh East train station.

Fig. 13. Riyadh transport map. Source: RCRC.

Fig. 13. Riyadh transport map. Source: RCRC.

Fig. 14. Pedestrians leaving the Al Sharkiya offices face significant barriers when attempting to cross the highway to reach bus stops on the opposite side of the road. Long walking distances between stops are further exacerbated by the lack of crossings and pedestrian-friendly facilities. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

The challenges posed by urban sprawl and low population density are substantial—not only in Dammam but also in Riyadh and other Saudi cities. At present, establishing an efficient public transport network is difficult without integrating mobility with urban planning. However, there is a growing commitment to transit-oriented development, focusing on creating urban areas centered around public transport hubs, in particular the metro and BRT.

As with all cities, addressing the "last mile" problem is critical to achieving a modal shift. This issue is particularly pressing in sprawling, car-centric cities with the harsh climate of Saudi Arabia.

Fig. 14. Pedestrians leaving the Al Sharkiya offices face significant barriers when attempting to cross the highway to reach bus stops on the opposite side of the road. Long walking distances between stops are further exacerbated by the lack of crossings and pedestrian-friendly facilities. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

The challenges posed by urban sprawl and low population density are substantial—not only in Dammam but also in Riyadh and other Saudi cities. At present, establishing an efficient public transport network is difficult without integrating mobility with urban planning. However, there is a growing commitment to transit-oriented development, focusing on creating urban areas centered around public transport hubs, in particular the metro and BRT.

As with all cities, addressing the "last mile" problem is critical to achieving a modal shift. This issue is particularly pressing in sprawling, car-centric cities with the harsh climate of Saudi Arabia.

Fig. 15. AlUla Valley mobility plan.

The tramway is a central component of the 360° mobility plan currently being developed by the Systra group. It plans to connect AlUla’s three main districts—tourist sites in the north, the administrative district in the center, and the residential area in the south—as well as linking these areas to the airport. Beyond the tramway, which serves as the backbone of the system, the different parts of the valley will also be connected by a cycle path, a bus network for more detailed service, and shuttles to bridge the gaps between different modes of transport. During our visit, autonomous shuttles, still in the testing phase, were operating on a limited route, connecting the pedestrianized old town to a park-and-ride facility approximately 500 meters away. However, they were more of an attraction than a functional addition to the transport system. In the long term, these shuttles (which may not end up being autonomous after all) are expected to facilitate access to the tramway and other key locations within the planned car-free zone.

Fig. 15. AlUla Valley mobility plan.

The tramway is a central component of the 360° mobility plan currently being developed by the Systra group. It plans to connect AlUla’s three main districts—tourist sites in the north, the administrative district in the center, and the residential area in the south—as well as linking these areas to the airport. Beyond the tramway, which serves as the backbone of the system, the different parts of the valley will also be connected by a cycle path, a bus network for more detailed service, and shuttles to bridge the gaps between different modes of transport. During our visit, autonomous shuttles, still in the testing phase, were operating on a limited route, connecting the pedestrianized old town to a park-and-ride facility approximately 500 meters away. However, they were more of an attraction than a functional addition to the transport system. In the long term, these shuttles (which may not end up being autonomous after all) are expected to facilitate access to the tramway and other key locations within the planned car-free zone.

Fig.16. The cycle path through the city and desert of AlUla. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

Fig.16. The cycle path through the city and desert of AlUla. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

Fig. 17. Autonomous shuttle being tested at the AlUla Old Town site. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

Public transport usage has increased notably since the creation of a car-free zone, an initiative that operators hope to expand beyond the old city. Systra, the group leading this effort, envisions a significant reduction in car use, which would represent a groundbreaking shift for a country that has historically avoided directly challenging the dominance of automobiles. If successful, this restriction on cars would likely drive a greater adoption of alternative modes of transport, which are already diverse and expanding in AlUla.

Fig. 17. Autonomous shuttle being tested at the AlUla Old Town site. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

Public transport usage has increased notably since the creation of a car-free zone, an initiative that operators hope to expand beyond the old city. Systra, the group leading this effort, envisions a significant reduction in car use, which would represent a groundbreaking shift for a country that has historically avoided directly challenging the dominance of automobiles. If successful, this restriction on cars would likely drive a greater adoption of alternative modes of transport, which are already diverse and expanding in AlUla.

Fig. 18. Valet parking service on a shopping street in Riyadh. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

Fig. 18. Valet parking service on a shopping street in Riyadh. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

Fig.19. Train along the Riyadh-Dammam line. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

After the destruction of the Hejaz Railway by Lawrence of Arabia during World War I, the first rail line constructed by Saudi Arabia was the one connecting Riyadh-East to Dammam. Its freight services began in 1951, followed by passenger services in 1981, serving four intermediate cities: Al Kharj, Haradh, Hofuf, and Abaquaiq. It is the kingdom's oldest operational line and remains the busiest, enabling many travelers to commute daily between the peripheral cities and the two major hubs of Riyadh and Dammam.

Fig.19. Train along the Riyadh-Dammam line. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

After the destruction of the Hejaz Railway by Lawrence of Arabia during World War I, the first rail line constructed by Saudi Arabia was the one connecting Riyadh-East to Dammam. Its freight services began in 1951, followed by passenger services in 1981, serving four intermediate cities: Al Kharj, Haradh, Hofuf, and Abaquaiq. It is the kingdom's oldest operational line and remains the busiest, enabling many travelers to commute daily between the peripheral cities and the two major hubs of Riyadh and Dammam.

Fig.20. Dammam railway station. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

Riyadh East Station is situated near the city and will soon be connected to the orange metro line (see Riyadh network map, Fig. 13), enabling access via public transport—a feature currently unavailable. This improved intermodality, along with enhanced last-mile public transport options, is expected to encourage greater use of the train for travel to Dammam and intermediate cities. In contrast, the North Station, which serves as the terminus of the second group of lines between Riyadh and Gurayat (the North-South line), is located outside the city and is not connected to the metro network. In both cases, the train system is not designed for intercity travel that could serve smaller towns or additional stations within Riyadh or Dammam. Instead, the stations each function as a terminus located far from populated areas.

The third operational line in Saudi Arabia is the Al Haramain high-speed train, connecting the holy cities of Medina and Mecca via Jeddah, King Abdulaziz Airport, and King Abdullah Economic City. As its name indicates (Haramain, meaning "two holy cities"), the train primarily caters to pilgrims. It has dramatically reduced travel time between Medina and Mecca, cutting the journey from 5 hours by car or bus to just 2.5 hours.

Fig.20. Dammam railway station. Aniss Mezoued, 2024.

Riyadh East Station is situated near the city and will soon be connected to the orange metro line (see Riyadh network map, Fig. 13), enabling access via public transport—a feature currently unavailable. This improved intermodality, along with enhanced last-mile public transport options, is expected to encourage greater use of the train for travel to Dammam and intermediate cities. In contrast, the North Station, which serves as the terminus of the second group of lines between Riyadh and Gurayat (the North-South line), is located outside the city and is not connected to the metro network. In both cases, the train system is not designed for intercity travel that could serve smaller towns or additional stations within Riyadh or Dammam. Instead, the stations each function as a terminus located far from populated areas.

The third operational line in Saudi Arabia is the Al Haramain high-speed train, connecting the holy cities of Medina and Mecca via Jeddah, King Abdulaziz Airport, and King Abdullah Economic City. As its name indicates (Haramain, meaning "two holy cities"), the train primarily caters to pilgrims. It has dramatically reduced travel time between Medina and Mecca, cutting the journey from 5 hours by car or bus to just 2.5 hours.

Fig. 21. Map of the existing and projected railway network.

As it stands, Saudi Arabia's three main rail lines do not form a sufficiently dense network to support a long-distance mobility system capable of competing with air travel. The Saudi Railway Company (SAR) does not currently view this as a viable goal, given the significant investments made in airports and the deeply ingrained preference for air travel. Nonetheless, SAR is actively working to improve the rail network and enhance its offerings for passengers, signaling a commitment to future development.

The centerpiece of SAR's efforts is the flagship "Desert Bridge" project, a high-speed rail line that will connect Riyadh to Jeddah. Chinese companies are playing a key role in its construction. In addition, several other projects—indicated in gray on the map—aim to better connect the kingdom, linking existing cities with future urban developments, including Neom. However, the challenges of building and maintaining a railway network in Saudi Arabia are immense. The vast distances between cities, coupled with harsh environmental conditions such as sand and extreme heat, create significant maintenance hurdles. To address these issues, SAR is collaborating with international partners to develop specialized technologies tailored to these unique conditions.

Beyond technical and technological hurdles, the greatest challenge lies in making rail travel competitive with automobiles. Factors such as seamless connections between train lines, improved access to stations via public transport, multimodality, and increased travel speeds will all be critical in attracting passengers to the rail system in Saudi Arabia. While national investments are moving in this direction, integrating national and regional networks with local-scale mobility systems remains an unresolved challenge.

Fig. 21. Map of the existing and projected railway network.

As it stands, Saudi Arabia's three main rail lines do not form a sufficiently dense network to support a long-distance mobility system capable of competing with air travel. The Saudi Railway Company (SAR) does not currently view this as a viable goal, given the significant investments made in airports and the deeply ingrained preference for air travel. Nonetheless, SAR is actively working to improve the rail network and enhance its offerings for passengers, signaling a commitment to future development.

The centerpiece of SAR's efforts is the flagship "Desert Bridge" project, a high-speed rail line that will connect Riyadh to Jeddah. Chinese companies are playing a key role in its construction. In addition, several other projects—indicated in gray on the map—aim to better connect the kingdom, linking existing cities with future urban developments, including Neom. However, the challenges of building and maintaining a railway network in Saudi Arabia are immense. The vast distances between cities, coupled with harsh environmental conditions such as sand and extreme heat, create significant maintenance hurdles. To address these issues, SAR is collaborating with international partners to develop specialized technologies tailored to these unique conditions.

Beyond technical and technological hurdles, the greatest challenge lies in making rail travel competitive with automobiles. Factors such as seamless connections between train lines, improved access to stations via public transport, multimodality, and increased travel speeds will all be critical in attracting passengers to the rail system in Saudi Arabia. While national investments are moving in this direction, integrating national and regional networks with local-scale mobility systems remains an unresolved challenge.

Fig. 22. Public space in the center of AlUla.

Public transport projects are theoretically expected to foster proximity through the creation of public spaces within residential districts, the development of transit-oriented districts, etc. During our discussions with researchers and stakeholders, the concept of proximity frequently arose as an essential component of transforming Saudi cities dominated by cars. The "15-minute city" concept was mentioned multiple times, though always accompanied by an acknowledgment of the immense challenges of making it a reality in the current context.

As with public transport, building "local cities" faces significant hurdles, particularly urban sprawl and extreme weather conditions. The existing urban infrastructure is poorly suited to fostering proximity: many neighborhoods lack sidewalks, major roads are hazardous for pedestrians to cross, fences or barriers often divide areas, and city blocks are designed for cars. Furthermore, streets are typically wide and unshaded, with minimal vegetation. Lowering street-level temperatures and enabling active mobility during periods of intense heat are becoming critical challenges for urban planners.

According to Dr. Ezzat Al-Atroush, surveys conducted on a university campus indicate that high temperatures significantly discourage people from walking or using other active modes of transport. He emphasizes that cooling streets must be a priority. Inspired by experiments in Qatar, where air-conditioned streets and heat-reflective asphalt have been tested, Riyadh seems to be focusing on greening the city as a long-term solution. Under the Green Riyadh Project, the city plans to plant more than 7.5 million trees, greening streets, public squares, schoolyards, and public institution courtyards, as well as road and highway interchanges. A dedicated water recovery system at the neighborhood level is being developed to irrigate these trees sustainably. The program’s centerpiece is King Salman Park, a massive 16.6 km² green space - nearly five times the size of Central Park in New York - located on the site of Riyadh’s old airport in the heart of the city, making it a powerful symbol!

Fig. 22. Public space in the center of AlUla.

Public transport projects are theoretically expected to foster proximity through the creation of public spaces within residential districts, the development of transit-oriented districts, etc. During our discussions with researchers and stakeholders, the concept of proximity frequently arose as an essential component of transforming Saudi cities dominated by cars. The "15-minute city" concept was mentioned multiple times, though always accompanied by an acknowledgment of the immense challenges of making it a reality in the current context.

As with public transport, building "local cities" faces significant hurdles, particularly urban sprawl and extreme weather conditions. The existing urban infrastructure is poorly suited to fostering proximity: many neighborhoods lack sidewalks, major roads are hazardous for pedestrians to cross, fences or barriers often divide areas, and city blocks are designed for cars. Furthermore, streets are typically wide and unshaded, with minimal vegetation. Lowering street-level temperatures and enabling active mobility during periods of intense heat are becoming critical challenges for urban planners.

According to Dr. Ezzat Al-Atroush, surveys conducted on a university campus indicate that high temperatures significantly discourage people from walking or using other active modes of transport. He emphasizes that cooling streets must be a priority. Inspired by experiments in Qatar, where air-conditioned streets and heat-reflective asphalt have been tested, Riyadh seems to be focusing on greening the city as a long-term solution. Under the Green Riyadh Project, the city plans to plant more than 7.5 million trees, greening streets, public squares, schoolyards, and public institution courtyards, as well as road and highway interchanges. A dedicated water recovery system at the neighborhood level is being developed to irrigate these trees sustainably. The program’s centerpiece is King Salman Park, a massive 16.6 km² green space - nearly five times the size of Central Park in New York - located on the site of Riyadh’s old airport in the heart of the city, making it a powerful symbol!

Fig.23. Green Riyadh project exhibition.

The development and redevelopment of public spaces is increasingly becoming a key factor in fostering proximity, both in Saudi Arabia and globally. These spaces play a dual role: helping to lower temperatures and mitigating climatic constraints while providing the necessary infrastructure for active mobility. They are also essential as spatial foundations for these mobility solutions.

In Riyadh, however, the greening and redevelopment of public spaces are more often framed as initiatives to enhance quality of life rather than as measures to improve mobility. Active modes of transport are not widely viewed as viable alternatives to motorized travel but are instead perceived as recreational or sports activities – cycling in particular. One of the capital's landmark megaprojects in this regard is the Sports Boulevard, a 135-kilometer corridor that spans the entire city. As the name suggests, the project aims to promote sports and physical activity, particularly cycling, but also includes cultural components.

Fig.23. Green Riyadh project exhibition.

The development and redevelopment of public spaces is increasingly becoming a key factor in fostering proximity, both in Saudi Arabia and globally. These spaces play a dual role: helping to lower temperatures and mitigating climatic constraints while providing the necessary infrastructure for active mobility. They are also essential as spatial foundations for these mobility solutions.

In Riyadh, however, the greening and redevelopment of public spaces are more often framed as initiatives to enhance quality of life rather than as measures to improve mobility. Active modes of transport are not widely viewed as viable alternatives to motorized travel but are instead perceived as recreational or sports activities – cycling in particular. One of the capital's landmark megaprojects in this regard is the Sports Boulevard, a 135-kilometer corridor that spans the entire city. As the name suggests, the project aims to promote sports and physical activity, particularly cycling, but also includes cultural components.

Fig. 24. Map of the Sports Boulevard that is under construction.

For some stakeholders, such as the Youth Saudi Society, the shift toward new mobility practices—similar to the adoption of public transport—will come through experimentation. They believe that sport and its associated infrastructure can serve as a gateway to fostering interest in active modes of transport, particularly cycling. This approach is evident not only in Riyadh but also in AlUla, where a 50-kilometer cycling path has been constructed along the valley, often cutting through the desert. The path connects the valley’s three main districts and even extends beyond the airport to the south. While AlUla’s climate is milder than Riyadh’s, summer temperatures still reach extreme levels. As a result, the path’s usability is significantly limited outside the city, as it is exposed to direct sunlight, with no vegetation or cooling systems to mitigate the heat.

Fig. 24. Map of the Sports Boulevard that is under construction.

For some stakeholders, such as the Youth Saudi Society, the shift toward new mobility practices—similar to the adoption of public transport—will come through experimentation. They believe that sport and its associated infrastructure can serve as a gateway to fostering interest in active modes of transport, particularly cycling. This approach is evident not only in Riyadh but also in AlUla, where a 50-kilometer cycling path has been constructed along the valley, often cutting through the desert. The path connects the valley’s three main districts and even extends beyond the airport to the south. While AlUla’s climate is milder than Riyadh’s, summer temperatures still reach extreme levels. As a result, the path’s usability is significantly limited outside the city, as it is exposed to direct sunlight, with no vegetation or cooling systems to mitigate the heat.

Fig.25. Cycle path from AlUla to the southern districts.

Among the three cities visited, Dammam is where the concepts of proximity and active mobility are at the earliest stages of development, despite numerous and relatively advanced projects. Notably, efforts to construct or rehabilitate entire neighborhoods are underway, with a focus on public transportation access, adopting the principles of the 15-minute city, and limiting car usage. One particularly innovative idea emerged during discussions with the Eastern Development Authority (Al Sharkiya): the transformation of the city and oil industry has led to many pipelines being decommissioned, leaving empty servitude corridors that cut across the city. Al Sharkiya wants to repurpose them into pathways for pedestrians and cyclists, alongside the development of public and green spaces. This initiative is highly symbolic here in the home of Aramco!

However, in all three cities visited, active mobility infrastructure is primarily presented as a means to promote sports and leisure rather than as functional transportation systems. A slight exception can be observed in AlUla, where we saw some workers using bicycles for practical purposes. AlUla’s 360° mobility plan incorporates cycling paths as complementary infrastructure to public transport, but without densification or the installation of cooling systems, cycling on these paths is likely to remain limited to recreational and sports activities rather than daily commuting.

Elsewhere in the Kingdom, two cities stand out in terms of active mobility: Jeddah and Medina. Both cities demonstrate particular advantages, especially in walkability. Jeddah has maintained a rich tradition of pedestrianization in the historic Al-Balad district, further complemented by the key attraction: the Corniche, a several-kilometer-long waterfront promenade, mostly for locals, designed entirely for leisure and free of motorized vehicles.

Fig.25. Cycle path from AlUla to the southern districts.

Among the three cities visited, Dammam is where the concepts of proximity and active mobility are at the earliest stages of development, despite numerous and relatively advanced projects. Notably, efforts to construct or rehabilitate entire neighborhoods are underway, with a focus on public transportation access, adopting the principles of the 15-minute city, and limiting car usage. One particularly innovative idea emerged during discussions with the Eastern Development Authority (Al Sharkiya): the transformation of the city and oil industry has led to many pipelines being decommissioned, leaving empty servitude corridors that cut across the city. Al Sharkiya wants to repurpose them into pathways for pedestrians and cyclists, alongside the development of public and green spaces. This initiative is highly symbolic here in the home of Aramco!

However, in all three cities visited, active mobility infrastructure is primarily presented as a means to promote sports and leisure rather than as functional transportation systems. A slight exception can be observed in AlUla, where we saw some workers using bicycles for practical purposes. AlUla’s 360° mobility plan incorporates cycling paths as complementary infrastructure to public transport, but without densification or the installation of cooling systems, cycling on these paths is likely to remain limited to recreational and sports activities rather than daily commuting.

Elsewhere in the Kingdom, two cities stand out in terms of active mobility: Jeddah and Medina. Both cities demonstrate particular advantages, especially in walkability. Jeddah has maintained a rich tradition of pedestrianization in the historic Al-Balad district, further complemented by the key attraction: the Corniche, a several-kilometer-long waterfront promenade, mostly for locals, designed entirely for leisure and free of motorized vehicles.

Fig. 26. Central lane reserved for active modes in Jeddah

Medina is making strides toward becoming a "human-scale city" by pedestrianizing many streets to improve the daily lives of both pilgrims and residents. Alongside these efforts, a network of cycle paths has been installed, complemented by self-service bicycles.

Fig. 26. Central lane reserved for active modes in Jeddah

Medina is making strides toward becoming a "human-scale city" by pedestrianizing many streets to improve the daily lives of both pilgrims and residents. Alongside these efforts, a network of cycle paths has been installed, complemented by self-service bicycles.

Fig.27. Signage for the “humanization” project of Medina’s city center streets, which includes pedestrianization and the creation of shared spaces along several central avenues.

Fig.27. Signage for the “humanization” project of Medina’s city center streets, which includes pedestrianization and the creation of shared spaces along several central avenues.

Fig.28. Self-service bicycles near Uhud Mountain, a place of religious interest.

These numerous initiatives highlight the circulation of global urban models and raise questions about their relevance in the Saudi context. While there is a clear global trend toward promoting active mobility and proximity, implementing kilometers of cycling and pedestrian infrastructure to meet key performance indicators or follow global trends will not suffice to establish sustainable active mobility practices in Saudi Arabia’s unique setting. The success of such initiatives depends on the integration of a fine-grained network that connects public spaces and active mobility infrastructure. This must be closely aligned with urban planning efforts, including the reconfiguration of car-dominated urban forms and the diversification of activities in single-use neighborhoods. Simultaneously, deploying this fine mesh of active mobility infrastructure must go hand in hand with greening public spaces and introducing cooling measures. Without these elements, the “last kilometer” will remain unaddressed, particularly in a country with Saudi Arabia’s extreme climatic conditions. However, based on the projects we observed and the interviews we conducted, these critical elements still lack clarity in current planning. The integration of active modes into the overall mobility system, particularly to address the last mile, remains an unresolved challenge.

Fig.28. Self-service bicycles near Uhud Mountain, a place of religious interest.

These numerous initiatives highlight the circulation of global urban models and raise questions about their relevance in the Saudi context. While there is a clear global trend toward promoting active mobility and proximity, implementing kilometers of cycling and pedestrian infrastructure to meet key performance indicators or follow global trends will not suffice to establish sustainable active mobility practices in Saudi Arabia’s unique setting. The success of such initiatives depends on the integration of a fine-grained network that connects public spaces and active mobility infrastructure. This must be closely aligned with urban planning efforts, including the reconfiguration of car-dominated urban forms and the diversification of activities in single-use neighborhoods. Simultaneously, deploying this fine mesh of active mobility infrastructure must go hand in hand with greening public spaces and introducing cooling measures. Without these elements, the “last kilometer” will remain unaddressed, particularly in a country with Saudi Arabia’s extreme climatic conditions. However, based on the projects we observed and the interviews we conducted, these critical elements still lack clarity in current planning. The integration of active modes into the overall mobility system, particularly to address the last mile, remains an unresolved challenge.